(I have written about many of these people, places and events earlier, but this is the first time I have attempted to put it all together. And I still have questions. But, given that I started this in 2001, I thought I’d better share what I have now and tack on new information as it comes.)

In the 1790s, if you wanted to travel westward from Fort Schulyer, today’s Utica, you followed the Iroquois Trail, a footpath that wound its way through forests and swamps, along rivers and streams, all the way to Fort Niagara. Roads west were not impassable or impossible. They simply didn’t exist.

And yet people wrote letters and sent them west, to be carried by Native Americans, settlers, traders, trappers, anyone going in the right direction on foot or on horseback.

A typical postman of the era was Luther Harvey, who carried the mail between the settlements of Buffalo and Erie. In good weather, he went on horseback. In bad weather he went on foot, as his horse was unable to pass through the dense woods and swamps. Once, going from Buffalo, Harvey was chased by wolves all the way to Fredonia (then a settlement with one house).

The young nation acquired a Postmaster even before it won independence; Benjamin Franklin was named Postmaster General at the second Continental Congress on July 26, 1775. The formal Post Office Department was created in 1792, as a service to the people and a way to link the new states together.

The first post office in Onondaga county was established in 1794 at Onondaga Hollow (Onondaga Valley) with Comfort Tyler as postmaster. A post office was established at Marcellus in 1799.

Enter William Vredenburgh, a shipping merchant from New York City. In 1797, the village of Skaneateles consisted of two or three log huts and one unfinished frame house. An early investor in the land around the outlet was Jedediah Sanger. His lots were selling for $8 apiece. In 1798, Vredenburgh began to buy them, and in the spring of 1803 he moved here from New York.

William Vredenburgh was the Village’s first certifiably wealthy resident. At one time, he owned most of the land on which the Village now stands. He built the first mansion overlooking the lake. He was connected to influential people. And he liked to get his mail.

Since his arrival in Skaneateles, he had been obliged to send someone to Marcellus to pick up his letters and wait for their return. He was unhappy with the arrangement. His solution was to call for a post office in Skaneateles with himself as the postmaster.

In November of 1803, Vredenburgh’s son-in-law, Charles Burnett, wrote from New York to his wife Maria, “have shown your Papa’s letter about the Post Office to Mr. Ten Eyck who will attend to it as soon as he has an opportunity to see DeWitt Clinton.”

DeWitt Clinton was the Mayor of New York but it was not his office that gave him influence over the appointment of post masters. Rather, DeWitt Clinton knew who to ask. His uncle, George Clinton, for whom DeWitt acted as personal secretary from 1789 to 1795, would soon serve as Vice President under Thomas Jefferson during his second term. Jefferson’s Postmaster General was Gideon Granger.

In April of 1804, William Vredenburgh’s appointment as Deputy Postmaster at Skaneateles arrived, signed by Granger. The charter bore upon its seal a figure of Mercury with the motto, Sigillum Magnum Generalis Nunciorum, i.e., Great Seal of the General of the Messengers.

At first, the mail was delivered to Vredenburgh’s house, twice a week, and distributed from there. The first post office building, a short walk from Vrendenburgh’s house, was a small wooden structure on the present site of St. James Episcopal Church. The front half held the post office and a store, and the back half, partitioned from the front, was furnished with benches for Sunday services.

At the same time, actual roads were being built. In 1794, the state legislature authorized the Great Genesee Road, following the Iroquois Trail, to help settlers reach the New Military Tract, lands set aside for veterans of the American Revolution. This vast tract included Skaneateles Lake.

In 1800, the legislature chartered the private Seneca Road Company to improve and maintain the road. The “old” Seneca Turnpike passed just north of the village. But one of the commissioners of the Seneca Road Company was Jedediah Sanger. To protect the value of his holdings, he secured the road’s passage through the village with the “new” Seneca Turnpike, which, perhaps by sheer coincidence, passed right by William Vredenburgh’s house.

The company built the first bridge across the outlet, and the improved road reached the village in 1804. Because the New Seneca Turnpike, the Cherry Valley Turnpike and the Hamilton & Skaneateles Turnpike all passed through Skaneateles, the village was a nexus for stage routes. By 1820, as many as 15 stage coaches a day passed through the village. And the coaches carried U.S. mail.

About the stage coaches: The Post Office Department at this time did not have a legion of neatly uniformed employees. Rather, they hired individuals or companies to deliver the mail. One of the first to carry the mail to Skaneateles was a young man named Isaac Sherwood. When he won a contract to carry mail west from Onondaga Hill, he carried it on foot. But soon he was aided by a horse, and then a wagon. When people began asking for rides on the wagon, he upgraded to a stagecoach. From the coach, he built an empire, owning and investing in stage lines running across the state from Albany to Buffalo.

Sherwood’s name lives on at the present-day Sherwood Inn, built on the site of the inn he raised in 1807 to serve his stagecoach trade. But the inn was also the site of some contention; coaches coming from the east with mail rolled right by the post office and instead stopped at Sherwood’s inn, where the horses, drivers and passengers could be refreshed. Thus the postmaster had to walk to the inn to retrieve the mail.

In 1813, Vredenburgh died, and on June 1, his friend John Ten Eyck took over as Postmaster, serving until 1817. On March 28, 1817, Charles J. Burnett, Vredenburgh’s son-in-law, became Postmaster.

When the original wood-frame building was removed to make way for the first St. James’ church, Burnett moved the post office to his store, on the site of what is now 32 East Genesee St., just west of the alley, in 2020 the home of Berkshire Hathaway Homes/CNY Realty.

In Burnett’s time, serving as postmaster had its challenges; precise records had to be kept of all mail coming in and going out, with the amounts (sometimes in fractions of a cent) calculated, charged and recorded for each. As of 1816, there were five different rates based on distance, from 6 cents for a letter going less than 30 miles, to 25 cents (which equals $5 in 2020) for a letter going more than 400 miles.

In his Notes of Other Days in Skaneateles, William Beauchamp noted, “Postage was high and most people sent letters collect on the principle that if a letter was worth reading, it was worth paying for.” Although convenient for the sender, requiring the recipient to pay the postage created a backlog of unclaimed letters at the post office, a list of which had to be advertised each month, at the postmaster’s expense, in the local paper.

In 1838, the village’s first railroad was chartered, to run on wooden rails from Skaneateles to Skaneateles Junction, where it met the Auburn & Syracuse Railroad. The cars were drawn by horses; iron rails and locomotives were yet to come. On July 12, 1839, the first mail by rail arrived in the village. Soon after, the stage coach lines lost their mail contracts to the railroads running across the state.

In July of 1843, Joel Thayer was made Postmaster, replacing Charles Burnett who had been Postmaster since 1817. This began a new era of postmasters being changed with every national election, as the post was a patronage “plum” for members of the winning party. The Cortland Whig saw Burnett’s removal in blatantly political terms:

“Mr. Charles M. Burnett, who has held the office for a good many years, is pronounced too honest a man for the work [President John] Tyler has on hand, while Joel Thayer, a zealous Loco Foco [Democrat] is found willing to take the office on the usual terms—servility to John Tyler.”

In his Notes of Other Days in Skaneateles, William Beauchamp noted:

“The change stirred up the wrath of my Quaker friend, James Rattle. I saw him ride — well, much like the riding of Jehu — into town, and vigorously rebuke Mr. Thayer, in the style of the Hebrew prophets, for taking another man’s office. The change, however, brought improved conditions.” (The Biblical allusion is to II Kings 9:20, in which Jehu drives his chariot furiously.)

The problem of unclaimed letters continued; in January of 1846, Thayer posted, in the Skaneateles Columbian, a list of 90 villagers who had not claimed (and paid for) their mail.

Taking a step in the right direction, on March 3, 1847, Congress authorized the manufacture and use of postage stamps for pre-paying postage. The stamps were printed on pregummed, nonperforated sheets, and clerks used scissors to cut them out.

In 1848, Joel Thayer, Postmaster, awarded Joel Thayer, Superintendent of the Skaneateles & Jordan Railroad Company, a $260 contract for carrying the U.S. mail.

On April 11, 1849, Thayer was replaced by John Snook Jr., the village druggist. The new Postmaster moved the post office to his drug store next to Legg Hall (in 2020, 62 East Genesee Street, home of Aristocats & Dogs).

In 1850, the original Skaneateles Railroad declared bankruptcy and the mail went off the rails, once again carried to and from Skaneateles Junction by wagon.

In 1853, Josias Garlock was appointed Postmaster and the post office moved five doors west (in 2020, 42 East Genesee Street, home of Loft 42). The Skaneateles Democrat noted, “From the business habits and character of Mr. Garlock, the public have every assurance that nothing will be left undone on his part to render every accommodation to them that may be justly expected.”

The Democrat’s editor added, “One word in regard to the retiring Postmaster—Mr. J. Snook, Jr. … Although opposed in politics, it would be simple justice to him to say that he has discharged the duties evolving from the office with fidelity, and credit to himself and constituency, and gave very general satisfaction to the community.”

In 1855, pre-payment of postage became the law, and it was no longer necessary to advertise the names of people with mail waiting.

In 1861, the Civil War began, and Horace Hazen was named Postmaster. During his term, the Skaneateles post office became an official “money order office.” The system was established in 1864 to enable Union soldiers to send money home to any place with a U.S. post office, reducing the risk of sending cash through the mail.

In 1866, Joel Thayer got a charter to build a new railroad. The tracks were completed and passenger service began in July of 1867, and once again the U.S. mail arrived from Syracuse via the railroad.

Forest G. Weeks was appointed Postmaster in 1869 when Ulysses S. Grant became President. The Syracuse Daily Standard reported:

“The old post office was located in what is called ‘Bank Block,’ which was an inconvenient and unsuitable place; it is now decidedly central, with pleasant surroundings. The office occupies the main part of the first floor of the store of John B. Marshall. An entire new and elegant set of boxes, five hundred in number, and twenty-four back drawers, have been constructed, with a tasty ornamental front, which, together with other outlays, has cost the new postmaster about two hundred dollars. The improvement meets the approval and approbation of the whole community.”

In 1874, on Sweet’s map of Skaneateles, the post office is the second door to the west of Legg Hall. This is today (2020) the home of Nest 58, at 58 E. Genesee Street.

John B. Marshall was Weeks’ Deputy Postmaster, and in 1873 he replaced Weeks who ran afoul of party powers when he opposed the re-election of Congressman R. Holland Duell.

In May of 1880, the Skaneateles Railroad declined the government mail contract, saying it did not offer enough compensation, and instead the contract was awarded to Mort Conover, who carried the mail by horse-drawn wagon. However, one month later, the mail contract was returned to the Skaneateles Railroad and the mail was back on the rails.

Between 1897 and 1908, the mail was brought from the Junction by James Gallagher with his horse and wagon. In 11 years of service, he was late only once, when the snow was four feet deep.

John B. Marshall served until 1885, and in February of that year was feted at a complimentary dinner, hosted by “men of all parties” at the Packwood House. After his term, he continued to operate his store and supply those taking boats down the lake. A camper wrote in 1885:

“A good recommendation brought us to Marshall’s store, where the late popular postmaster deals out the choicest wares to housekeepers and campers, and the recommendation held good. This is one prime requisite of a successful camp, for it is no joke to have poor articles when far away in the woods.”

Appointed by Grover Cleveland, Marshall’s replacement was Edson G. Gillett, a veteran of the Civil War who fought at the siege of Petersburg and served with General Sherman in the Shenandoah campaign. After his term as Postmaster, Gillett returned to the dairy industry, and in 1910 delivered a paper, “My Personal Experience as a Buttermaker,” at the Butter & Cheese Makers convention in Ithaca.

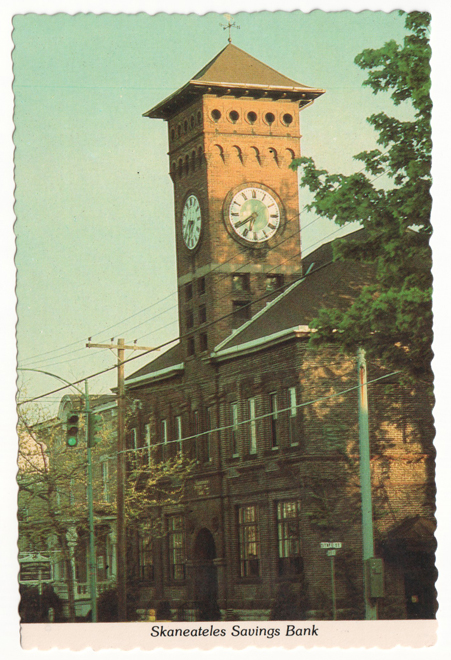

On January 20, 1894, J. Horatio Earll was appointed postmaster by the “new administration.” From March 1, 1894, to 1902, the Post Office was in the “corner store” of the Eckett Block, later known as the Seitz Building, on the northwest corner of Jordan and Genesee Streets, today (2020) the home of Skaneateles 300.

Postmaster Earll’s post office had the distinction of hosting a robbery. In the early morning hours of February 27, 1897, two men pried open a window and crawled inside. One set to work with a chisel on all the drawers and boxes; the other drilled a hole in the top of the safe and dropped in a stick of dynamite.

The blast blew the door off, shattered every window, and alerted the village’s night watchman, Oliver Edwards, who was on his rounds at the livery stable behind the Packwood House (today’s Sherwood Inn). As Edwards ran across the bridge over the outlet, a man with a gun stepped out of the shadows and said, “Halt, and throw up your hands.”

Edwards threw lead instead, emptying his 7-shot revolver at the shadowy figure, who responded in kind. Neither managed to hit the other. The gunman’s companions sprinted from the post office and all three ran up Jordan Street with stamps, cash, money orders and checks. Apparently they had a buggy waiting and vanished, leaving behind two chisels, a drill bit and a real mess.

William J. Bright was appointed Postmaster under the administration of President William McKinley, and served from 1898 to 1902. After McKinley’s death and Theodore Roosevelt’s rise to the Presidency, there was a six-month snit between opposing factions of the Republican party in Skaneateles. Each faction had its own choice for the postmaster’s job. One side wanted Bright to remain, and the other wanted John T. Palmer to take his place.

Roosevelt wanted to please the second faction, but would not replace a veteran without cause. Bright was a veteran of the Civil War, serving in the 148th New York Volunteers, and had been widely praised for this work as postmaster. So the second faction found their own veteran, George B. Harwood, and he was appointed, serving from 1902 to 1910.

On July 1, 1902, the Post Office moved to 5 E. Genesee Street, in the space now (2020) occupied by S.J. Moore Jewelers.

Henry T. Tucker served as Postmaster from 1910 to 1914, after clerking for J. Horatio Earll and then serving as Assistant Postmaster for the entirety of George Harwood’s term. In June of 1910 the Skaneateles Free Press noted, “His appointment is a genuine application of civil service rules.”

During Tucker’s term, the Postal Savings System was introduced. The system sought to coax money out of mattresses and cookie jars, appeal to immigrants used to saving at post offices in their native countries, and provide a safe depository for those who had lost confidence in banks. The minimum deposit was $1. To save smaller amounts, customers could purchase a 10-cent postal savings card and 10-cent postal savings stamps to fill it. When the card’s value amounted to $1 or more, it could be used to open or add to an account.

William H. Hennessey served as Postmaster from 1914 to 1923. He was nominated by President Woodrow Wilson upon the recommendation of Congressman John R. Clancy. However, “anti-organization” forces put forth Lester Harse, a long-time clerk in the Skaneateles post office. Hennessey prevailed and was confirmed by the Senate in October of 1914. On April 1, 1921, he announced the initiation of home delivery in the village.

L. to R.: John Simmons, William H. Hennessey (seated), Walter Cavell, Clarence Simmons, Earl Kelly, Frank Stearns, Lester Harse

Before serving as postmaster, Hennessey was a cigar manufacturer. In May of 1906, the Skaneateles Free Press noted, “W.H. Hennessey’s cigar factory is now running in full blast, being unable to keep up with its orders. Five men are employed, besides the proprietor.” Among the hundreds of cigars rolled every day were the ‘Opulent’ and the ‘Little Planter.’

Even more interesting to me, Hennessey was the president of the St. Mary’s Temperance Society, which “continuously exerted a practical and useful influence along temperance lines.” In one of those sibling contrasts that make families interesting, Michael F. Hennessey, his brother, was the proprietor of Hennessey’s Cafe, the forerunner of McLaren’s, Morris’s Grill, and the LakeHouse Pub. And the “Cafe” served liquor even on Sundays, until it was busted and fined $500 in 1905.

But back to the mail.

John Simmons, shown above in the Hennessey post office photo, was the area’s first rural mail carrier. He began making his rounds in 1901, covering a 24-mile route on the west side of the lake on horseback. In 1920, Simmons retired, having covered 140,000 miles on seven horses under four Skaneateles Postmasters and six Postmaster Generals.

On October 1, 1920, Raymond P. Dougherty, a “husky, jovial, friendly, likeable” man, began work as a substitute carrier in the Village of Skaneateles. On April 1, 1927, he was appointed as the first regular mail carrier in the Village.

In March of 1921, William A. Hilton began circulating a petition asking to be appointed postmaster of Skaneateles. The Skaneateles Press noted, “Mr. Hilton is a popular citizen. He has been manager of the Auburn and Syracuse trolley station in Skaneateles and is at present in charge of the trolley freight office in Auburn, but maintaining his residence in Skaneateles.” Perhaps he foresaw the effect the automobile would have on the trolley business, and his efforts bore fruit. Hilton was appointed postmaster by President Calvin Coolidge and served from 1923 to 1936. Offering a glimpse into the ways of bureaucracy, the Congressional Record of 1928 noted, “William A. Hilton to be postmaster at Skaneateles, N.Y., in place of W.A. Hilton.”

In 1936, Walter F. Herrling was appointed Postmaster by Franklin D. Roosevelt. Herrling was the first Skaneateles Postmaster to take and pass the Civil Service test, in 1940. Also that year, Herrling was tasked with registering alien residents 14-years-old or older, in person, taking their fingerprints and recording their addresses. Parents could register their children, who did not need to be present. The newspaper added, on a cheery note, “There is no charge of any kind connected with alien registration.” As of November 1940, the Skaneateles post office had registered more than 100 aliens living in Skaneateles, Marcellus, Jordan and Elbridge.

Once the U.S. entered World War II, Herrling was also responsible for updating postal regulations for overseas mail. For example, in March of 1943, Herrling shared the official notice that mail for French West Africa, French Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia (unoccupied) was limited to letters only (no parcels). And no mail would be dispatched to those parts of Tunisia occupied by Axis forces. Obviously, these destinations were a moving target for the postal services throughout the war.

In 1947, when the postmaster’s worries were limited to the Christmas rush, the Skaneateles post office sold $72,500 worth of 1- and ½-cent postage stamps for outgoing Christmas cards.

In 1951, Herrling retired and was replaced by Paul H. Irving, who would see the post office through the transition from manual processing to automation, and the move into a new post office building.

Planning for the new post office had dragged on for years. The eventual site was just west of the Outlet, on a spot with a busy history. Once owned by New York state, the lot was used by villagers as an impromptu storage space for wagons. In 1904, the state granted the lot’s care to the Women’s Village Improvement Association (WVIA) which created Elm Park, with benches and plantings. In 1907, the WVIA added a sundial atop a large boulder in the park’s center, and it became known as Sundial Park. Eventually, the state formally granted the land to the Village “for park purposes.” New state legislation would be required for any other use. When the Federal government expressed interest in the site for a new post office, that legislation was enacted, giving the Village the ability to sell the land to the government, which then had the first option on the property. But the Village’s offer languished in Washington.

After WWII, communities across the nation were concerned about what could be done for returning veterans. When the American Legion expressed interest in buying Sundial Park as a site for a Legion hall, the Village Board checked and found that the Federal government’s option to buy had expired. In January of 1948, state legislation was introduced to alter the “park purposes” covenant and enable the Legion to buy the land. Discussions began between the Village and the Legion, resulting in a spoken agreement.

But late in 1949, the Federal government again expressed interest in the site for a new post office. This put the Village in a bind. The Village wanted a new post office, but the Village Board had given its word to the Legion.

Early in 1950, the Legion graciously offered to release the Village from its agreement in exchange for another site, 26 acres of empty land on Jordan Street. The Village accepted the Legion’s offer and was then free to sell Sundial Park to the U.S. as a site for a new post office. In 1958, after eight years of jumping through hoops, the Village sold Sundial Park to the Federal government. But then the government changed course, deciding to lease land for its post offices, rather than buy. So Sundial Park was sold by the government to an investor who leased it back to the government.

On December 10, 1962, after more than 12 years of dithering, the Village’s first dedicated U.S. Post Office opened at 14 West Genesee Street (in 2020, the site of the second Packwood House), bringing to an end the era of storefront post offices.

In early February of 1966, there was no mail, due to the Blizzard of ‘66. “Nobody could move,” said mailman Tom Garbo.

In April of 1966, the Postal Savings System stopped accepting deposits and Postmaster Irving urged depositors to withdraw their savings as soon as possible.

During the Christmas rush of 1967, parcels without the new ZIP codes were refused at the counter, and patrons had to line up at the ZIP code book to get the numbers and add them to their addresses.

In 1968, Irving defended the price increase for First Class postage, saying the six-cent stamp was “still one of the best bargains in the world.” And in January of 1971, Irving welcomed two sheep, Sissy and Little Inky, at the post office, brought in to celebrate a stamp commemorating the 450th anniversary of the introduction of sheep to North America.

In 1972, Bill Pavlus became Postmaster, appointed by the Postmaster General rather than the President, as the era of political appointments ended. In 1978, there were 14 postal workers in the Village post office, serving 1,622 homes on four rural routes and 1,127 homes on three Village routes. In 1987, Postmaster Pavlus was honored at “Citizen of the Year” by the Chamber of Commerce.

Charles F. Tanner, who had served as Assistant Postmaster, was appointed in 1993 and oversaw the move to the new post office at 20-22 Fennell Street. Plans were approved in 1996; two homes were razed; building progressed and on August 7, 1997, the post office we know today opened.

Since the opening, the Postmasters have included Cynthia M. Donnelly, 2009-2014, Mark E. Lawrence, 2014-2016, and Brian T. Hayes, 2017.

Mail on the Water

In 1823, to bar steamboat captains from carrying mail outside the government’s postal monopoly, the U.S. Congress declared waterways to be post roads. Thus in 1831, when the steamboat Independence was launched on Skaneateles Lake, it instantly created a mail route, in spite of carrying no mail.

Far down the lake, the Glen Haven Water Cure Sanitarium was founded in 1847, treating ailments with cold water, cold baths, long walks, and meatless meals. As the property’s reputation grew, the “summer resort” aspect was emphasized. In 1885, the newly built Glen Haven Hotel offered 250 guest rooms and the luxury of flush toilets. Summer guests came by the hundreds and most arrived by steamboat from Skaneateles.

But between 1850 and 1859, guests had no nearby post office to send their letters to the outside world. The closest was four miles south in the tiny hamlet of Scott, with a larger post office seven miles farther on, in the town of Homer. As a service to its guests, Glen Haven opened its own “supplementary” post office where letters were collected and carried to Homer (when the weather was good) or to the closer post office in Scott (if the weather was bad).

The cost for the service was one penny per letter. Each outgoing envelope carried a Glen Haven Daily Mail stamp, in addition to the U.S. postage, signifying that the penny had been paid.

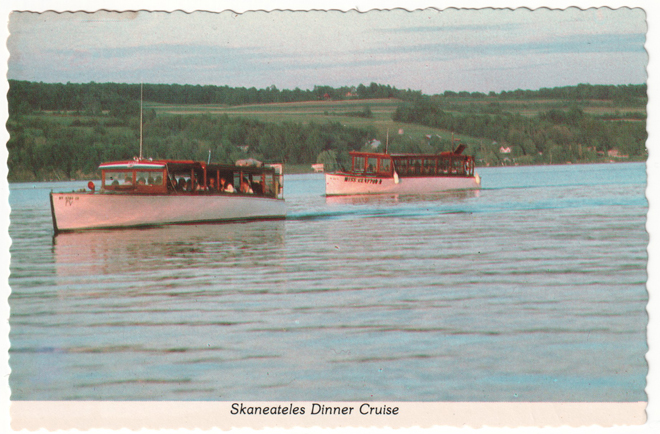

For those who put off writing their vacation postcards until the return trip to Skaneateles, there were post offices on the steamboats. Built in 1876, the steamer Glen Haven had its post office located just behind the wheel house on the upper deck. A postal clerk was a regular member of the crew. Every envelope and postcard mailed onboard bore an “RPO” postmark, Railway Post Office, as the railroad owned the Skaneateles Navigation Company.

In 1901, the Skaneateles Navigation Company launched The City of Syracuse, a larger steamer. Like the Glen Haven, it too had a mail room. In 1904, the steamboats were sold by the Skaneateles Railroad to the Auburn & Syracuse Electric Railroad, i.e., “the trolley company.”

Competition from the automobile, new roads and new vacation spots in the Thousand Islands and Adirondacks caused the Glen Haven Hotel to close in 1911. The city of Syracuse bought the Glen Haven property and carted off the buildings to eliminate possible sources of contamination from the city’s water supply.

The two steamboats continued to run, serving the cottages, but the trolley company withdrew from their operation at the end of the summer of 1914. A company formed by Skaneateles merchants and cottage owners ran the steamboats during the summer of 1915, but discontinued the service at the end of the summer. Instead, the Lotos, originally owned by Frederick Roosevelt, was brought into service for the summer of 1916 by the Barber Boat Company, and was the only mailboat on the lake

The Glen Haven and City of Syracuse sank in the outlet in 1917, conclusively ending their chapter in the story.

In 1917, George Barber & Son [Leslie Barber] introduced the Rose, a 50-foot launch built for them and named for a member of the family. A 1919 Barber Boat Line time-table noted, “A morning boat leaving Skaneateles will deliver U.S. Mail, Express and Camp Supplies to the individual docks. Bring your lunch baskets and enjoy a trip around the most beautiful lake in America.”

The original Ossahinta, a steamboat that carried rowdy passengers with kegs of beer rather than mail, was a contemporary of the Glen Haven and City of Syracuse. But a second Ossahinta, so named to confuse historians, was pressed into service for delivering the mail. One August afternoon, Capt. Welton Myers and mail clerk Carlton Hardwich paused in their deliveries to rescue five boaters whose craft had burned to the water line off Five Mile Point.

The Florence was built in 1922 for the Cottage Owners Association, a non-profit organization of summer cottagers. She was named for the manager’s daughter, Florence Keegan, and carried mail and groceries to camps up and down the lake, making about 40 stops. The Florence ran throughout the 1920s and 30s, but was replaced by a new launch, the Spray, in 1941, run by the Stinson Boat Line, Inc.

However, the Florence was not finished. In December of 1941, the U.S. was pushed into World War II by the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. This prompted gasoline rationing on the home front and sent Bill, Bob and Don Stinson off to war service. In the summer of 1943, Edwin “Doc” Arthur filled in. In August of 1943, Allie J. Hoffman, of Hoffman’s Pharmacy, bought the derelict Florence from the Village and refitted her to run as a steam launch. In the summers of 1944 and ’45, she was back on her route, with Hoffman’s daughter, Betty, working as the mail clerk. It was a fitting encore for the Florence after her years of service.

From 1946 to 1966, Bob and Don Stinson delivered the mail on the lake. The Spray served from 1946 to 1952, followed by the Gloria V from 1953 to 1956, then Miss Pat a.k.a. Pat II from 1956 to 1966. (Pat II was a tour boat in the Thousand Islands from 1924 to 1955.) Auxiliary boats included Miss Nan and Sylvia, the latter named for the wife of the previous owner, cartoonist and illustrator Frank Godwin.

In the mid-1950s, while in high school, Lew Allyn crewed on the Gloria V for two summers. He said the best thing about the mail boat was Don Stinson. “He was a professor at Loyola College in Chicago and a great character. He knew the lake and he loved the lake. I couldn’t have asked for a better mentor.”

On occasion, there was more to the job than mail delivery. After one wild, stormy night when the lake claimed the lives of two fishermen, only one body was found. Stinson said, “We’re out here more than most people, so we’re more likely to find the other body. If you spot it, just step back and I’ll take care of it.” And so it happened.

On a happier note, Allyn enjoyed sorting the mail at the post office with Nelle Glass and Paul Irving before each trip, meeting interesting people, and being on the water. “It was a great education, a great initiation,” he said.

During the summer of 1964, the lake level was low, with no water in the docking area at Clift Park. Mail and passengers had to board from the city of Syracuse’s boathouse. Don Stinson paid local youngsters “a nickel a rock” to deepen the channel each morning so the boat could make it out to open water.

In 1968, Peter Wiles Sr. formed Mid-Lakes Navigation, purchasing Pat II (shown above) and the government mail contract for Star Route 13. (Legislation in 1845 called for contractors to carry the mail with “celerity, certainty and security.” Weary of writing the three words in ledgers, clerks substituted three asterisks — * * * — and the phrase “Star Route” was born.)

In the summer of 1970, Mid-Lakes hired its first mail girl, Rebecca Gourley, an 18-year-old whose family had recently moved to Skaneateles. Rebecca was on her way to Boston University in the fall, but would spent one summer getting a tuition-free education on the mailboat. She began her day by sorting the mail at the post office and bringing it across the street to the boat. On the lake, she delivered the mail using a net on a long pole, and between deliveries handed out sandwiches to passengers who were along for the ride.

In May of 1971, Wiles added Miss Clayton II, a boat built in 1927 and first used as a rum-runner in the Thousand Islands during Prohibition. The next mail boat began life as a pleasure craft. Built in 1935, The Roamer was a private runabout on the St. Lawrence River. In 1981, Mid-Lakes bought The Roamer and rechristened it The Barbara S. Wiles, after the wife of Peter Wiles Sr. and the daughter of Gustav Stickley.

In 2019, after a half-century of service, the Wiles family announced the sale of Mid-Lakes Navigation, with the mailboat and Judge dinner cruises going to William Eberhardt, owner of the Sherwood Inn. “We feel like we couldn’t have wrapped this up any better,” Sarah Wiles said. “The company will continue with new leadership, and it will honor everything we have built.”

In the summer of 2020, both the Judge and the Barbara S. Wiles are back on the water, and the mailboat is delivering the mail.

Air Mail

On May 19, 1938, Postmaster Walter Herrling drove out Onondaga Street with about 1,000 pieces of mail. A short ride outside the Village limits, he came to the Frank Evans’ farm to meet pilot Eugene Horle and make history. The occasion was National Air Mail Week, during which postmasters across New York State used volunteer pilots to fly mail to designated terminals. Horle loaded up and took to the skies for Syracuse with the Village’s first-ever air mail.

In Syracuse, the Skaneateles letters joined with others from dozens of small towns and were sent “to all corners of the world.” (Or right back to collectors who had addressed letters to themselves so they could own a piece of history.)

Frank Evans’ farm had an earlier brush with air mail: One afternoon, Grace Evans, the youngest of Evans’ seven children, was walking home from school when she saw a plane flying low and ran to see it land. She recalled, “The pilot walked to our house and phoned Syracuse, and they came for him and the mail. They left the plane and came for it the next morning.” The pilot was Merle Moltrop (Grace never forgot his name), who in 1927 flew the first air mail out of Pittsburgh.

Nathan Kelsey Hall

No postal history of Skaneateles would be complete without a tribute to Nathan Kelsey Hall, the Postmaster General of the United States from 1850 to 1852. Hall was born in the Town of Skaneateles before it was Skaneateles, when the Town of Marcellus still reached all the way south to the lake.

At the age of 16, he clerked for Millard Fillmore at his law office in East Aurora. Professionally and personally, Fillmore and Hall worked well together. Both came from the Finger Lakes. Both rose from difficult circumstances. Each saw in the other someone they could trust.

In 1830, Fillmore and Hall began to practice law in Buffalo. Both thrived in business and politics, holding a succession of local and state offices. Elected to Congress for three terms, Fillmore was added to the Whig’s presidential ticket in 1848 to attract New York voters. Fillmore was meant to help win the election, and then disappear. But in July of 1850, President Zachary Taylor died and Fillmore became President. And Fillmore brought his close friend, Nathan Kelsey Hall, into his Cabinet.

As Postmaster General, Nathan Hall remained true to form; he was honest, methodical, loyal. He requested bids for the making of postage stamps, and actually gave the job to the firm best qualified. Many histories mention that such an act was a stunning development.

During Hall’s term, he oversaw the reduction of postage to three cents for domestic letters sent up to 3000 miles. He later noted, “That the revenues of the Department have been perennially diminished by these reductions cannot be denied; but it is believed that this diminution has been slight in comparison with the public benefits which have followed.”

Hall, like Benjamin Franklin, saw the Post Office as a service to the people, as an important way of linking the states, of forging its far-flung citizens into one nation. Under the stewardship of men like Franklin and Hall, there was never a mention of the Post Office being self-sufficient or run like a business.

Selected Sources

“More Tylerism,” The Cortland Whig, July 18, 1843

“Postmaster,” Skaneateles Democrat, May 6, 1853

Souvenirs of Some Early Days in Skaneateles, N.Y., William Beauchamp, 1882

“A Camp on the Lake,” ‘B.,’ The Baldwinsville Gazette & Farmer’s Journal, August 6, 1885

“History of the Town of Skaneateles,” Onondaga’s Centennial, Dwight Bruce, ed., 1896

Skaneateles: History of its Earliest Settlement and Reminiscences of Later Times, Edmund Norman Leslie, 1902

“Postmaster George B. Harwood,” Skaneateles Free Press, April 18, 1902

“Notes of Other Days,” William Beauchamp, Onondaga Historical Association Annual, 1914

Notes on the Vredenburgh and Burnett Families, E. Reuel Smith, 1917

Barber Boat Line Time-Table, 1919

“Early Local History: Roads,” Jabez W. Abell, Cazenovia Republican, June 24, 1925

Skaneateles History, Sedgwick Smith, circa 1938 (unpublished)

The Private Local Posts of the United States: Volume 1, New York State, Donald Scott Patton, 1967

“Watery Rounds,” Syracuse Herald-American, September 15, 1968

The Story of the Steamboats on Skaneateles Lake, Charles B. Cooper, 1979

“Special Delivery,” Carmela Monk, Post-Standard Neighbors, July 13, 1989

“Skaneateles — Not Your Average, Daily Mail Route,” Carol Cleaveland, n.s.

Short Lines of Central New York, Richard F. Palmer, 1996

Letter from Grace Evans McKnight, June 4, 2001

“The Skaneateles Post Office, 200th Anniversary,” Beth Battle, 2004

“The Glen Haven Sanitarium and Summer Home” by Alice Anderson and “Mailboat Delivery” in ReEcho: Celebrating the First One Hundred Years of the Glen Haven School and Public Library, 2007

“Postal Savings System,” United States Postal Service, July 2008

“After more than 50 years, family to sell Skaneateles tour boat company,” Elizabeth Doran, syracuse.com, September 30, 2019

My thanks to Rebecca Gourley Stephenson and Lew Allyn for sharing their memories, to Dr. Melissa Conway for the Latin translation, to Scott Ouderkirk for the mailboat art, and to the ever indispensable Fulton database for access to millions of New York newspaper pages from the past.