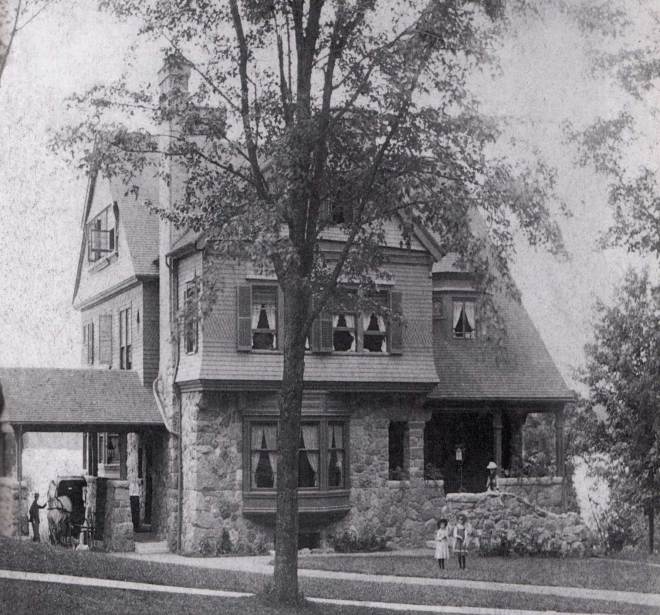

Joseph Clarence Willetts has a unique memorial in Skaneateles: The Boulders (noted as “The Bowlders” in its early days), a home on Genesee Street with large stones distinguishing the first story of the main house and the boathouse.

The Boulders first served as a summer home, but it was a long summer; the Willetts family would arrive in the spring and generally leave around November 1st, their arrivals and departures noted in both the New York Times and the Skaneateles Press. In the fall, Mrs. Willetts, the former Emma Calista Prentice of Brooklyn, returned to New York; Mr. Willetts accompanied her, or continued on to warmer climes, California or the South, for his health.

Joseph C. Willetts was a wealthy businessman, serving as president and director of Associated Farms, the Dexter Folder Co., and the New Domestic Sewing Machine Co. He was the secretary and a director of Syracuse Chilled Plow Co., as well as a director of Toledo Carriage Woodwork Co. and the Williams Typewriter Co. In Skaneateles, he was vice president and a director of the Bank of Skaneateles, and active with the Skaneateles Library Association and St. James’ Episcopal Church.

Willetts was also an ardent naturalist, and in 1882 sent four fish from Skaneateles Lake to the U.S. National Museum.

And now, a chronology of The Boulders:

:: 1883 ::

On April 7th, The Free Press reports that ground has been broken for the cellar of J.C. Willetts’ new house on Genesee Street. For at least two years, Willetts has been personally selecting boulders for the construction of his home. In April, the Skaneateles Press reports:

“A man from Rochester is engaged in blasting field boulders on J.C. Willetts’ premises in this village. The stones are to be used in Mr. Willett’s new house. Dynamite is used, the cartridge being simply covered with a shovelful of earth on the top of the boulder, with a fuse about a foot long. The dynamite does its work effectively, and is far superior to powder.”

One can imagine what kind of a spring that was for the neighbors.

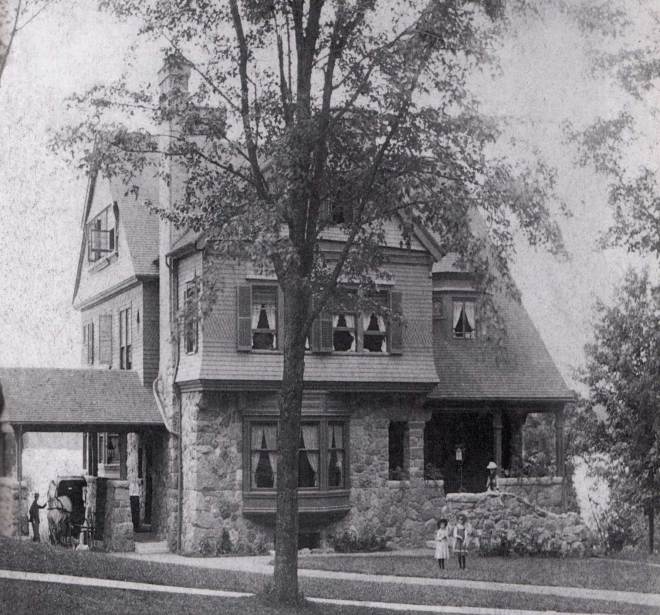

This photo was taken in July:

The man atop the stone wall is carrying a roll of plans, and is thought to be the architect.

:: 1884 ::

In January, the Auburn News and Bulletin reports:

“An Auburn builder, James C. Stout, takes an important contract in competition with several celebrated firms in Albany and Syracuse, to execute the inside finish of an elegant residence for J.C. Willetts, Skaneateles. The work is to be done in cherry, oak and mahogany. The plans are by Green & Wicks of this city.”

In June, the Skaneateles Free Press reports that J.C. Willetts is occupying his new house.

:: 1886 ::

On October 9th, the Skaneateles Press confirms the identity of the architect of The Boulders, in an article about the new Skaneateles library building:

“Its construction will probably be in the hands of Mr. Green of Buffalo, whose work is familiar to Syracusans in the Frazer block on Billings Park, and in several unusually pretty dwellings, among them the Willetts residence in Skaneateles, and the Case cottage [Casowasco] on Owasco lake.”

“Mr. Green” is architect Edward Brodhead Green (1855-1950), born in Utica, N.Y., and educated at Cornell University. His partnership with William S. Wicks, Green & Wicks, started in Auburn, N.Y., in 1880, and moved to Buffalo, N.Y., in 1881.

On October 17th, the Willetts’ first son, Joseph Prentice Willetts, is born in Brooklyn. He has an older sister, Amie (born in 1877), who is named for her grandmother, Amie Frost Willetts Lapham. The lad will be educated at Miss Reynolds’ School and the Cutler School.

:: 1888 ::

In March, architect Edward B. Green visits Skaneateles to present plans for the new library building. He is the guest of J.C. Willetts, a director of the library board, at The Boulders.

In June, a second daughter, Marion Willetts, is born in Skaneateles.

:: 1890 ::

In March, Joseph Willetts is elected president of the Village of Skaneateles.

On May 13th, William Allen Willetts is born in Skaneateles.

In December, The Boulders is almost lost. The Syracuse Weekly Express writes:

“The home of J. C. Willetts in Genesee street barely escaped being burned Saturday morning. The fire originated from an overheated steam pipe in the basement and did quite a little damage before the blaze was extinguished.”

:: 1899 ::

The Willetts’ eldest son, Joseph Prentice Willetts, enters St. Paul’s School, in Concord, N.H., where he will letter in hockey and football, row with the crew and join the literary society as well.

:: 1900 ::

The U.S. Census finds all six members of the Willetts family at home in Skaneateles, with three servants: Lizzie Seibert, Violet Tibo (Thibeau?) and Bessie Guigham.

:: 1904 ::

On August 31st, Joseph C. Willetts dies at The Boulders, at about 7 o’clock in the evening. He had been ill since the previous autumn, and since coming to Skaneateles from New York in June, had “steadily failed in health.” He was just 58 years old. His obituary remembers him as “a man of liberal ideas and generous impulses.” His funeral is held at home, and he is buried in Lake View Cemetery, which he, as president of the Cemetery Commission, had done much to beautify.

:: 1905 ::

Joseph Prentice Willetts enters Harvard University. In the next four years, he will play hockey, football, row crew, serve on the student council and class day committee, and be a member of the Polo, Hasty Pudding, Fly, and St. Paul’s School clubs.

:: 1906 ::

In the summer, Mrs. Willetts tours the Berkshires with friends.

On September 25th, Amie Willetts marries Samuel Roosevelt Outerbridge at St. James’ Episcopal Church. The groom is the son of Ellen Roosevelt Outerbridge who is the sister of Samuel Montgomery Roosevelt, the daughter of Samuel Roosevelt and the granddaughter of Nicholas Roosevelt, who lived across the street from The Boulders on the west corner of Leitch and Genesee. Amie is escorted down the aisle by her brother, Joseph Prentice Willetts.

The Auburn Weekly Bulletin reports:

“Following the ceremony, breakfast was served at the Bowlders, the beautiful summer home of Mrs. Joseph C. Willetts situated on the shores of Skaneateles lake. The bride’s table was charmingly decorated with white anemones and asparagus ferns. Kapp’s orchestra of Syracuse furnished the music. The bride received many beautiful and valuable gifts.”

A graduate of Harvard, Class of ’97, Mr. Outerbridge is a partner in the firm of A. Emilius Outerbridge Co., Ltd., running steamship lines to Bermuda and the West Indies. The couple will make their home in Oyster Bay, L.I., N.Y.

:: 1907 ::

In February, the Harvard Crimson writes:

“The University hockey team defeated the second by a score of 4 to 1 in a fast practice yesterday afternoon in the Stadium rink. All the scoring of the first team was the result of close team work. The goals were made on passes or from scrimmages, while the second team’s only point was due to a brilliant individual rush by Leonard. Toward the end of the second half, the second seven made a number of hard rushes down the rink with excellent passing, but were prevented from scoring by Washburn’s steady defensive play at goal. Foster, Willetts, and Carpenter, the University defense, played on the second team, so as to give the University forwards as much hard practice as possible.

“During the practice Willetts had his nose broken; this is not expected to interfere with his playing throughout the remainder of the season.”

Emma, Joseph Prentice and Marion spend Christmas at The Boulders. Marion brings two friends, probably from Miss Master’s School in Dobbs Ferry, where she is a student.

:: 1908 ::

On February 28th, Joseph P. Willetts, Class of ’09, is elected captain of the Harvard hockey team. Willetts has played point on the team for the past three years, and is a three-time All American. In the 1908-09 season, his team is undefeated. He is noted for “absolute fearlessness” and is said to possess a personality that infuses confidence into his teammates.

In April, the Skaneateles Democrat reports that The Boulders’ chimneys have been repaired.

:: 1909 ::

Joseph Prentice Willetts graduates from Harvard and begins work at the Syracuse Chilled Plow Company, “starting at the bottom.” He leaves Skaneateles each morning by the 6 a.m. trolley and returns home in the evening. He often shares his lunch with “the more unfortunate men,” and makes it a point to visit any workman who is hospitalized.

On December 29th, Marion Willetts marries Ernest Cuyler Brower, an attorney of Brooklyn, N.Y., at St. James’ Episcopal Church. The bride’s sister, Amie, now Mrs. Samuel Outerbridge, is matron of honor, and their elder brother, John Prentice Willetts, escorts the bride down the aisle.

The Skaneateles Press notes:

“Following the ceremony a wedding breakfast was served at The Bowlders, Mrs. Willetts’ magnificent home, by Teall of Rochester to about one hundred guests from New York, Rochester, Syracuse, Auburn, Skaneateles and other places. The bride’s table was decorated with orchids and maidenhair ferns.

“Mrs. Willetts’ home, always beautiful, was gorgeously but tastefully decorated with Christmas greens tied with red ribbons, holly branches and poinsettia blossoms.”

The Auburn Citizen adds:

“The Willetts home was elaborately decorated in Christmas greens, great masses of holly being hung in all rooms and hallways, while banks of Christmas trees enhanced the beauty of the green and red of the Yuletide decoration.”

:: 1910 ::

On June 29th, after a six-week siege of typhoid fever, Joseph Prentice Willetts dies at The Boulders. He is remembered as one who had no enemies, a person of constant good cheer, and for “his absolute lack of conceit or thought of himself.” His funeral is held at home. He is one of 23 members of Harvard’s Class of ’09 to die in 1910.

In the autumn, William Allen Willetts enters Harvard; he will change his middle name from Allen to Prentice, to carry on his mother’s family name.

Samuel Roosevelt Outerbridge reports to the Harvard annual that he and Amie now have two children, Joseph Willetts Outerbridge (b. 1907) and Marion Ellen Outerbridge (b. 1910). Of his steamship company, he writes, “I am still a partner, but am not getting rich,” and adds, “Beyond the usual round of social activities of city life in the winters, and the simple life of the suburban commuter in the summers, the narrative of my experiences must be left to a fertile imagination to make them interesting.”

:: 1911 ::

Mrs. Willetts does not open The Boulders, but rather spends the summer motoring in Europe.

:: 1912 ::

In June, Mrs. Willetts hosts a house party for her son William, gathering his “young society friends” at The Boulders. The party includes Elsie Pollard, Pauline Pollard, Sidney Clark, Stephan Hopkins, Alvin Foye Sortwell (the son of the Mayor of Cambridge, Massachusetts), Magnus Swanson, Helen Whitney, George Bourne and John Angus Milholland. Clark is William’s closest friend from Harvard; William will marry Sidney’s sister, Christine, in 1915. Alvin Sortwell will marry Elsie Pollard in 1914. J.A. Milholland, with whom William played football at Harvard, will marry Mandida Dundas Bareducci, of Italy and New York, at Meadowmount, his father’s 1000-acre estate, before sailing for Java where the groom is in the export trade. All in all, a colorful gathering.

:: 1913 ::

The Harvard hockey team spends the Christmas holiday at The Boulders, guests of the team captain, William Prentice Willetts. The lads travel to Syracuse to play four games, splitting their two games with Syracuse and losing twice to Ottawa.

:: 1914 ::

After graduating from Harvard, William Prentice Willetts spends the summer in Norway with his mother and his fiancee, Christine Newhall Clark.

:: 1915 ::

In June, William Prentice Willetts weds Christine Clark and, after “a month’s splendid honeymoon,” returns to Brooklyn and begins working for E.W. Bliss Co. By the following year, he is in charge of 400 men who load and ship high explosive shells to war-torn Europe.

Mrs. Clarence Hancock and Mrs. Stewart Hancock summer at The Boulders, and host “a large tea” in September.

:: 1916 ::

William Prentice Willetts goes to Wall Street and at the same time learns to fly, rising at 4 a.m. to go to the airfield, then rushing to Hallgarten & Co. to be there by 9 a.m. and deal with bond issues. He is commissioned as a First Lieutenant in the Signal Officers Reserve Corps, Aviation Section.

In November, he is one of 12 pilots to take part in the first mass cross-country flight of military aircraft, from Mineola, Long Island, to Princeton, New Jersey. Their mission: to attend the Princeton-Yale game. The pilots fly over the field, performing aerial acrobatics, before landing nearby and taking seats in the stadium. And so aviation history is made.

:: 1917 ::

On March 21st, Willetts participates in another aviation first: the first aerial funeral cortege. The deceased is 22-year-old pilot Tex Millman; 12 airplanes escort him to the cemetery in Westbury, Long Island. Three drop wreaths upon the grave site and then all 12 planes form a cross as they pass over the funeral service.

In December, William is sent to Washington, D.C., beginning a tour of duty that takes him to every aviation field in the United States. The following year, he is discharged and goes to work for a steel company.

:: 1919 ::

On June 1st, the Syracuse Post-Standard headlines an article “ ‘The Boulders’ Sold by Mrs. J.C. Willetts to Senator Hendricks” and reports:

“ ‘The Boulders’ has been known for years as one of the finest places in Skaneateles, and derives its name from the style of construction employed on the residence and boathouse. It took Mr. Willetts a number of years to get the boulders, which were split and used for the first story of both buildings.

“The property, is located in Genesee Street, between the residence of Mrs. James Holland Davis and the rectory of St. James’s Episcopal Church, and was part of the original estate of Mrs. Charles H. Poor. It has a front of 150 feet; and extends back 140 feet to the lake. The transaction includes the purchase of the house furnishings and all equipment of the boathouse, including a launch and numerous smaller boats. The boathouse has a living room with a fireplace, and in the house proper there are numerous fireplaces.

“The house is one of the most spacious in the village and has been the scene of many large house parties at which prominent men and women were entertained for long periods. The first floor has a large entrance hall extending the length of the house, and the balance of the floor contains a living room, library and dining room. The two latter rooms overlook the lake. The second and third floors have ten bedrooms, with numerous baths. The rooms have hardwood floors, and the trim is of selected cherry and oak with the walls decorated in oils.

“The purchase included a garden with residence for chauffeur and garage located in Academy street. The garden contains nearly two acres of land. The price paid by Mr. Hendricks is not made public Mr. Stone said yesterday that the Genesee street house alone cost Mr. Willetts $50,000.

“Since his death, the family has not opened the house every season, having established a summer residence on Long Island as well as at Skaneateles. Mr. Willetts and Mr. Hendricks were friends. Mr. Willetts had a wide acquaintance in Syracuse and entertained local people at his Skaneateles house on many occasions.”

In addition to being well known in politics, Francis Hendricks was the founder of the Hendricks Photo Supply Company, and the man who donated $500,000 to Syracuse University for Hendricks Chapel, named in memory of his wife.

On July 2, Hendricks has the Willett’s belongings sold at auction by W.H. Hetzel. Contents include a “massive” oak dining table, 12 leather-seat dining chairs, a high-post mahogany bed, a billiard table, antique guns, pistols and sabers, stuffed birds, bear robes, trunks, pictures, mirrors and crockery.

:: 1920 ::

In June, Francis Hendricks dies at his home in Syracuse, just one year after buying The Boulders. The estate of Senator Hendricks sells The Boulders to Allen V. Smith, head of Allen V. Smith Co., Inc., Marcellus, a miller of pearl barley and split peas. Smith, his wife Carrie, daughter Aleene, and sons Carlton and Richard move in.

In this, the first year of Prohibition, William Prentice Willetts reports to the Harvard annual, “We have been blessed with a small daughter, a smaller son, and a still smaller supply of liquor — here’s hoping they all multiply!

:: 1926 ::

On August 12th, this ad runs in the Skaneateles Press:

“LOST – Will the persons who were seen picking up an Angora kitten on Genesee St. kindly return same to the Boulders and avoid trouble. Richard Smith.”

:: 1927 ::

Marion Willetts Brower, widowed for two years, marries her brother-in-law, George E. Brower.

:: 1929 ::

On April 20th, Aleene Smith is married at The Boulders, to John Odell of Marcellus. The wedding is said to be the last one catered by Cora Krebs.

:: 1935 ::

Emma Prentice Willetts dies at her home on Park Avenue in Manhattan. Her New York Times obituary reminds us that her father, John H. Prentice, was the treasurer of the group that built the Brooklyn Bridge. Her daughter Marion’s second husband, George Brower, is now a justice of the New York State Supreme Court.

:: 1937 ::

Joseph Prentice Willetts, son of William Prentice Willetts, graduates from St. Paul’s School and enters Harvard University. Like his father and uncle, he will play hockey.

:: 1938 ::

In October, Alfred H. Gaylord buys The Boulders from Allen V. Smith. Gaylord is the vice president of Gaylord Bros., a stationery and library supply company in Syracuse. The company was founded by Alfred’s father, Henry Gaylord, and Alfred’s uncle, Willis Gaylord.

:: 1940 ::

In March, the Harvard Crimson writes:

“Prennie Willetts, left wing play-maker on the second forward trio, was unanimously elected to succeed Captain Bill Coleman as leader of next winter’s Varsity hockey attack, at a meeting of the team yesterday afternoon.

“Though an injured shoulder which he received before the Canadian trip, kept him on the bench during the last part of the season and handicapped him during the second Yale game, the new captain showed himself to be one of Clark Hodder’s strongest stickhandlers during the first part of the winter.

“Willetts captained his Freshman hockey team and has played left inside on the Varsity soccer team during the last two years, receiving a major H in the fall of 1938 for being a member of the team which won the Intercollegiate Soccer League title. From Roslyn Heights, Long Island, he prepared at St. Paul’s School and now lives at 52 Mt. Auburn Street.”

And this:

“With Prennie Willetts who has recovered from a shoulder injury, at his old wing position, Hodder will once again play his smooth-scoring combination of center Dave Eaton, Stacy Hulse, and Willetts in the second line. Teaming together until they were riddled by injurious several weeks ago, they accounted for most of the Crimson scores, and they should be able to account for at least a few tallies tonight.”

In October, The Crimson reports on soccer:

“Captain Dave Ives, in the right fullback position, heads a strong soccer eleven, out to garner its fourth win of the season. Jack Penson, goalie, Prennie Willetts, right outside, and Bill Edgar, center halfback will be counted on heavily by Coach Carr.”

:: 1941 ::

In February, on successive days, it’s back to the ice:

“In an attempt to shake the Crimson out of its doldrums, Hodder will ice the line which showed up best against the Tigers, with gridman Burgy Ayres flanked by Captain Prennie Willetts and George Duane.”

“Prennie Willetts provided the winning margin at 16:45 when he passed Hannock, the Williams net minder on a power play.”

:: 1942 ::

On March 30th, Joseph Prentice Willetts completes flight training and is commissioned as a Ensign; he marries Mary Louise Wiener, daughter of Mr. & Mrs. Gustav Blatz of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, on the same day in the Navy Chapel at Pensacola, Florida.

:: 1943 ::

On August 18th, Lt. Joseph Prentice Willetts, along with the 11 men on his Mariner aircraft, dies in a crash during a submarine-detection exercise off Montauk Point, Long Island.

:: 1944 ::

William Prentice Willetts and his wife, Christine N. Willetts, write and publish a book, The Loss of the Mariner PBM3-No. 9, VP-210, USN, and present it to the families of the lost officers and crew.

:: 1946 ::

William and Christine Willetts establish and endow a meteorology exhibit at the Hayden Planetarium of the American Museum of Natural History in memory of their son, Joseph Prentice Willetts.

:: 1949 ::

Alfred H. Gaylord dies at Syracuse Memorial Hospital following a heart attack. The Gaylord family sells The Boulders to Thomas Speno of Ithaca. Mr. Speno divides the dwelling into seven (7) apartments, turning it into The Boulders Apartment House.

Residents over the next two years will include Mr. & Mrs. W.H. Shackleton, of Cleveland, Ohio; Mr. & Mrs. Richard I. Bobbett, Mr. & Mrs. Robert Hettler, Mr. & Mrs. William E. Emerson, and Leonard Young.

:: 1951 ::

On August 17th, the Skaneateles Press reports a brush with death at The Boulders:

“W.C. Quarnstrom of Town Line Rd., Coon Hill, had a narrow escape from serious injury, if not death, about 8 p.m. last Thursday night when he slipped on a ramp in rear of The Boulders and fell into the lake… Donald Klump and A.L. Young Jr., both residents of The Boulders, swimming nearby, saw Quarnstrom fall, swam after him and brought the unconscious man to shore. A physician was summoned and examined the man, where it was found the injured man had a three-inch gash in his head.

“Quarnstrom recovered from his experience and is about as usual again.”

On August 24th, Arthur H. Poole of the Jefferson Electric Co., of Syracuse and Bellwood, Illinois, buys The Boulders apartment house from Thomas Speno, who has owned the property for just two years. Poole will occupy one of the apartments; his son and daughter-in-law, Mr. & Mrs. Allen H. Poole, will occupy another. Another tenant, Mrs. E. W. Cromwell, is mentioned in the local press.

The newspaper, for the first time, erroneously attributes The Boulders to architect Stanford White, a legend that will grow in the years to come.

:: 1952 ::

In January, two ads appear in the Skaneateles Press:

FIVE ROOM unfurnished apartment—two bedrooms, porch overlooking lake, lake privileges, heat, light, hot water, one block from shopping center. The Boulders, 100 E. Genesee Street. Skaneateles. (Available now—references).

AVAILABLE NOW — Three room apartment, one bedroom, heat, light and hot water, beautiful yard—lake privileges, one block from shopping center. The Boulders, 100 E. Genesee Street. Skaneateles, N.Y. (no pets). References.

:: 1953 ::

Samuel Roosevelt Outerbridge dies and is buried in the Willets family plot in Lake View Cemetery. In 1956, Amie Willetts Outerbridge dies and is buried at his side.

:: 1957 ::

In August, Dr. Albert Benjamin Smith moves his office (and his wife, DeEtta, and three daughters: Judith Madelene, DeEtta Anne, and Susan Adelene) from 2 West Lake Street to The Boulders; his office is at the back of the house on the lower level.

:: 1961 ::

Judith Smith goes to Mt. Holyoke, and DeEtta Smith, a student at Sweet Briar, studies in Paris for a year.

In May, a house tour program tells us that The Boulders’ stone foundation is five and a half feet thick, and the house has a chandelier ordered from Czechoslovakia by Mr. Willetts. Again, Stanford White is cited as the architect.

:: 1964 ::

William Prentice Willetts dies in Southern Pines, North Carolina.

:: 1995 ::

Dr. Albert B. Smith dies.

:: 2002 ::

In September, DeEtta G. Smith dies.

:: 2007 ::

The house is purchased from the Smith daughters by Elizabeth and Evan Dreyfuss, who make extensive renovations, removing two kitchens on the upper floors left from the apartment house days, and fully restoring the house to its original intent as a family residence. After the restoration is complete, the couple and their three children move into the house in December of 2008.

* * *

The United States Post Office introduced zone numbers in 1943, so we know the letterhead below dates from before that time.

Above, the Willetts family plot in Lake View Cemetery. The smaller stones (l.-r.) mark the graves of Joseph Prentice Willetts, Emma Prentice Willetts, Joseph C. Willetts, and on the opposite side of the large stone, Amie Willetts Outerbridge, Samuel Roosevelt Outerbridge and Amie Frost Willetts Lapham.

* * *

My thanks, as always, to the Skaneateles Historical Society, to Pat Blackler, Village Historian, and to Elizabeth and Evan Dreyfuss of The Boulders.