Mark Twain saw him at every opportunity, some times going to his show two or three nights in a row. He was one of America’s most amazing pianists, an autistic savant who performed as Blind Tom.

On April 27, 1874, Blind Tom played at Legg Hall. General admission was 50 cents, but reserved seats could be had for 75 cents, with tickets picked up in advance at Henry Hollon’s drug store.

Born a slave in Georgia, Tom Wiggins was blind and hence had no discernible economic value. The plantation owner, James Neil Bethune, left Tom to play and wander. As he grew, Tom began to echo the sounds around him, the crow of a rooster or the singing of a bird. He would beat on pots and pans to make sounds of his own. By the age of four, Tom was repeating, verbatim, the conversations of others, but was barely able to communicate his own needs in words, instead using grunts and gestures.

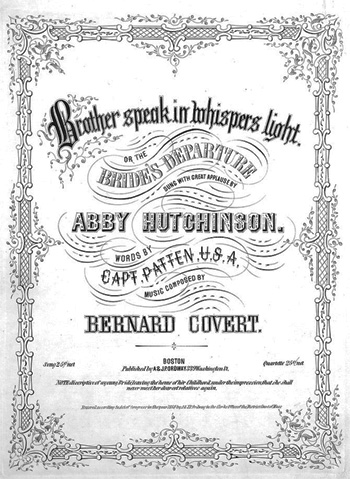

Fatefully, Tom was intrigued by the piano after hearing Bethune’s daughters play. As one writer of the day noted, “The first touch of a piano acted like a charm on this child.” In time, Tom was able to play all that he heard without missing a note. Bethune was fascinated by the boy’s talent and moved him into the family’s house, in a room with a piano, where Tom played for hours each day. Bethune hired professional musicians to play for Tom, and in this way the boy learned 7,000 popular songs, waltzes, hymns and classical pieces.

When Tom was eight, Bethune hired him out to promoter Perry Oliver, who toured him throughout the country, earning Bethune and Oliver up to $100,000 a year. In 1860, Blind Tom performed for President James Buchanan; he was the first African-American to give a command performance at the White House.

Tom usually introduced himself onstage in the third person, imitating the speeches of his managers from years past. Willa Cather described one such concert:

“It was a strange sight to see him walk out on stage with his own lips—another man’s words—introduce himself and talk quietly about his own idiocy. There was insanity, a grotesque horribleness about it that was interestingly unpleasant. One laughs at the man’s queer actions, and yet, after all, the sight is not laughable. It brings us too near to the things that we sane people do not like to think of.”

In August of 1869, Mark Twain was traveling across the country on his own lecture tour and attended a performance by Blind Tom. Writing for San Francisco’s Alta California newspaper, he reported:

“He lorded it over the emotions of his audience like an autocrat. He swept them like a storm, with his battle-pieces; he lulled them to rest again with melodies as tender as those we hear in dreams; he gladdened them with others that rippled through the charmed air as happily and cheerily as the riot the linnets make in California woods; and now and then he threw in queer imitations of the tuning of discordant harps and fiddles, and the groaning and wheezing of bag-pipes, that sent the rapt silence into tempests of laughter. And every time the audience applauded when a piece was finished, this happy innocent joined in and clapped his hands, too.”

And so it must have been in Legg Hall on that evening in 1874.

* * *

Sources:

The Skaneateles Democrat, April 1874

Quote by Willa Cather, Nebraska State Journal, May 18, 1895; it is believed that the character of Blind Samson d’Arnault in Cather’s My Antonia is based on Blind Tom.

Quote by Mark Twain, Alta California (newspaper, San Francisco), August 1, 1869

Thanks, of course, to the Fulton History Database and Google.