Once opened, the book on the Loney family of Skaneateles is hard to put down. Great wealth, the first American auto racing champion, a World War I ambulance driver, a Lusitania survivor — it’s all on the page.

:: The Patriarch ::

William Amos Loney (1822-1914)

William Amos Loney was a merchant from Baltimore who summered in Skaneateles. By his first wife, Ruth Ann Barker, he had a son, William (b.1849), and two daughters, Mary Loney (b.1851) and Ruth Arabella Loney (b. 1853). William’s first wife died young, and the children were raised by William and their grandmother, Elizabeth Barker.

Alice Louisa Allen Loney (1844-1907)

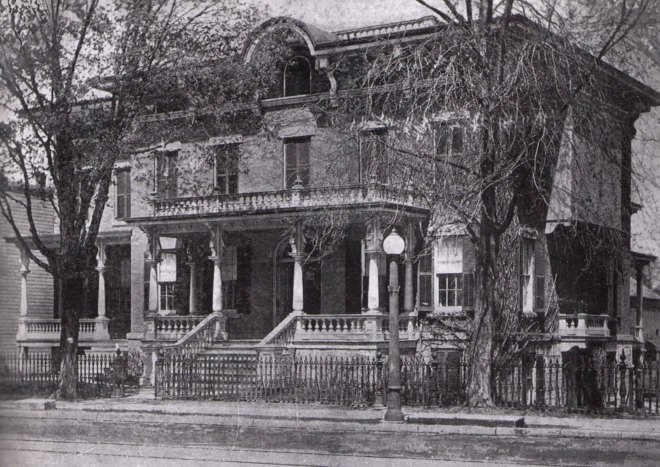

In 1863, William Loney met Alice Louisa Allen in Skaneateles. They were married in January of 1864. William Loney bought a small farm on Genesee Street and on the land built a 25-room summer home; the grand lawn behind his house sloped all the way to the lake.

The first Loney home, now The Athenaeum at 150 Genesee Street; the “back lawn” is today the site of Lake View Circle.

In the winters, William and Alice Loney lived in Baltimore; when William retired, the family moved to the village of Pelham in Westchester County. Every summer, they lived in Skaneateles, and worshipped at St. James’ Episcopal Church. Their marriage was blessed with four children: Alice Rebecca Loney (b.1866), Allen Donellan Loney (b.1871), Henry Edward Loney (b.1873) and Frederick Roosevelt Loney (b.1878)

Allen Donellan Loney, Frederick Roosevelt Loney, Henry Edward Loney, about 1879

In 1880, the U.S. census-taker found the William Loney family at home in Skaneateles: William (58) and Alice (36), daughters Ruth (24) and Alice (15), sons Allen (8), Henry (6) and Frederick (2), and three servants.

:: The Roosevelts and Roseleigh ::

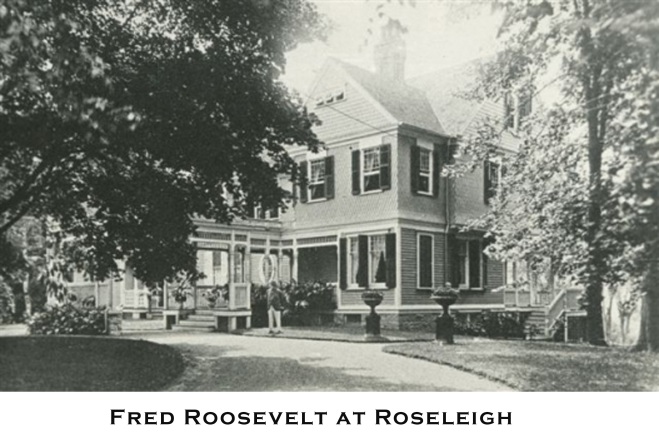

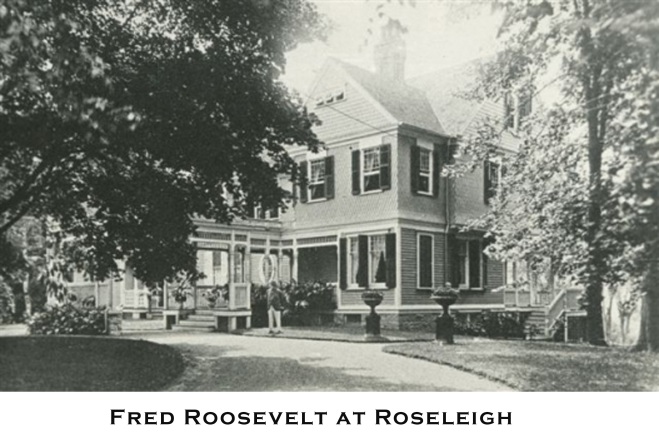

Around 1873, Mary Loney, William’s eldest daughter, married Frederick Roosevelt, son of James I. Roosevelt, a New York State Supreme Court Justice. Frederick and Mary lived in New York City, summered in Skaneateles, and often traveled abroad.

In January of 1879, Mary and Frederick purchased land in Skaneateles from Henry Latrobe Roosevelt. In March, they had a summer home designed by New York City architect William Rutherford Mead. The Roosevelts’ house was built in pieces in New York City, shipped to Skaneateles and assembled here in 1880 and 1881; the interiors were designed by Stanford White, who had recently joined Mead’s firm, which became McKim, Mead & White.

Mary and Frederick called their estate on the lake “Roseleigh.” It had 10 bedrooms, 4 baths, a billiard parlor, den, dining room and living room, with a fireplace in every room. It included a stable, a boat house and a generous expanse of shoreline.

Below, Roseleigh in 1907. The house became the Stella Maris Retreat & Renewal Center, which has since been demolished.

:: Marrying into Three Fortunes ::

Some time after 1880, Ruth Arabella Loney, William’s second daughter, married George Bruce-Brown (b. 1844) of New York City, a widower. He was the grandson of George Bruce and Catherine Wolfe Bruce, hence an heir to the fortune of his grandfather — a printer, type manufacturer and real estate investor — and to the fortune of the Wolfe family — which included a portion of the J.P. Lorillard tobacco fortune through Catherine Lorillard Wolfe.

Also, through George’s first marriage to Virginia Greenway McKesson, he was linked to the McKesson pharmaceutical fortune. George and Virginia had two children: a daughter, Catherine Wolfe Brown (b. 1877) and a son, George McKesson Brown (b.1878). George’s first wife, Virginia Bruce-Brown, died the year her son was born, but her name would live on in the next generation.

George and his new wife, Ruth Bruce-Brown, lived in New York City and on their estate on Long Island; they had two sons of their own, William Bruce-Brown (b.1886) and David Loney Bruce-Brown (b. 1887).

:: The Abbot Family ::

In 1890, William Loney gave his third daughter, Alice Rebecca Loney, in marriage to Mr. Harry Stephens Abbot, a Harvard man, in a ceremony at St. James’. The service was performed by the bride’s uncle, the Rev. Anthony Schuyler, and St. James’ rector, the Rev. Frank N. Westcott. Allen and Henry Loney, the bride’s brothers, were among the ushers. George and Ruth Bruce-Brown were in attendance, as was the bride’s uncle, Baltimore attorney Henry Donellan Loney. The sanctuary of St. James’ was decorated with flowers and the bridesmaids wore Gainsborough hats, the height of fashion. At the Loney home, also filled with flowers, an orchestra played for the couple’s reception.

:: The Second Loney Home ::

In 1891, with his children grown up and leaving the nest, William Loney sold his house on E. Genesee Street and moved with his wife Alice to a smaller house on the northeast corner of East Genesee and Leitch Avenue.

The second Loney home, 103 E. Genesee Street. today

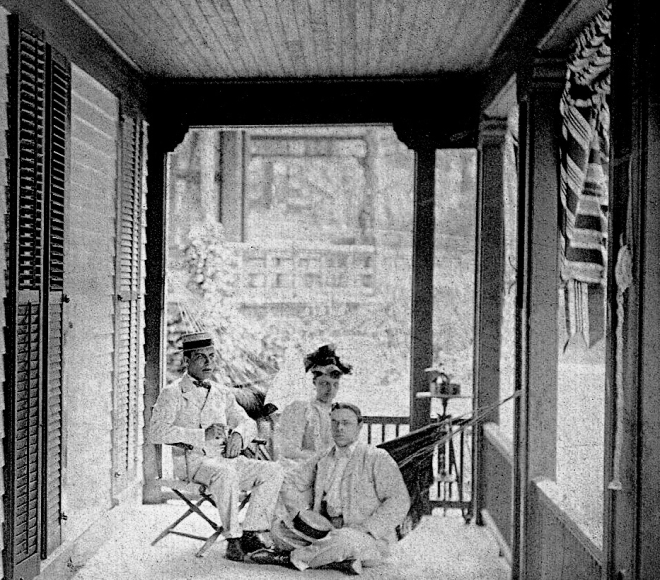

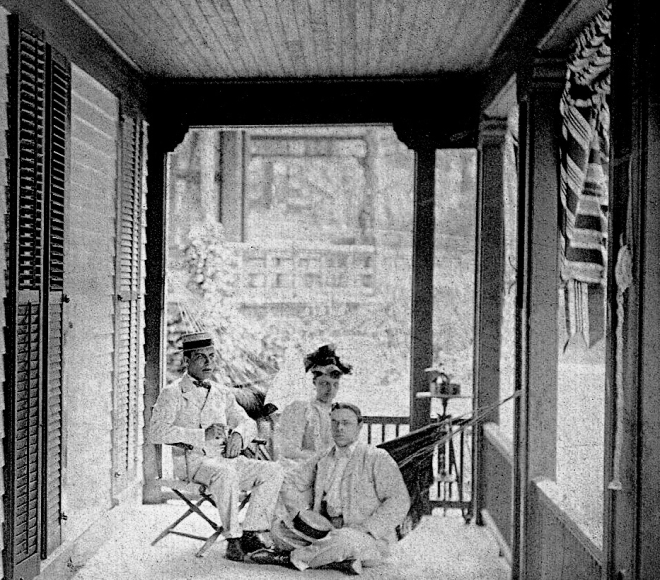

Alice Rebecca Loney, with her husband Harry Stephens Abbot and her brother, Frederick Roosevelt Loney on the porch at 103 E. Genesee

Alice Rebecca Loney, with her husband Harry Stephens Abbot and her brother, Frederick Roosevelt Loney on the porch at 103 E. Genesee

:: All in the Family ::

In 1892, George Bruce-Brown died at the age of 48, leaving Ruth, his 39-year-old widow, with four children, including George’s daughter Catherine, who was 15 years old. At some point, Catherine caught the eye of Ruth’s half-brother, Allen Loney, and by 1895, Allen and Catherine were married, living on Park Avenue with Catherine’s brother George, and listed in The Social Register. (And thus Allen Loney’s half-sister, Ruth Bruce-Brown, also became his stepmother-in-law.) Allen had a seat on the New York Stock Exchange, traded and sold bonds, but mostly he managed his wife’s money. The interest on the principle, by itself, came to $75,000 a year.

In 1894, Harry S. Abbot and Alice Rebecca (Loney) Abbot became the parents of a daughter, Alice Louise Abbot.

Alice Louise Abbot

:: Mary Norton Loney ::

In 1897, William Loney’s third son, Henry E. Loney, married Mary Hise Norton, the daughter of Eckstein Norton, a railroad president and Wall Street investor. Their wedding at Staten Island’s St. John’s Episcopal Church, with the Rev. Dr. Anthony Schuyler performing the service, was said to be the largest of the year; Mr. & Mrs. Andrew Carnegie were among the guests.

For two years, the newlyweds summered in Skaneateles at the home of Henry’s aunt, Mrs. T.Y. (Georgiana Allen) Avery at 91 East Genesee Street. In the fall of 1899, Henry and Mary Loney moved to Asheville, North Carolina. Perhaps Mary, who had lost a child, needed a milder climate. For whatever reason, the move did not help. Mary Norton Loney died on March 17, 1900. She was 24 years old; she and Henry had been married less than three years. Her body was brought to Lake View Cemetery in Skaneateles and interred in a tomb facing the lake.

Henry Loney went to Europe, noting on his passport application that he planned to return “within two years.” (He did return and remarried quietly in 1902, to Miss Henrietta de Rivera of New York, “noted for her vivacity and for her musical talents.” They would have a daughter, Isabelle, born in 1903.)

:: Virginia Loney ::

There was some good news in 1899: a daughter, Virginia Bruce Loney, was born to Catherine and Allen Loney. The family lived in New Rochelle, New York, with eight servants, one of whom was Elise Bouteiller, a French widow with two children of her own; she had come to the United States in 1887, and had been with the Loneys for many years; now, she was Virginia’s nurse.

Elise Bouteiller and Virginia Loney, about 1902. Photo courtesy of Paula Rosal, great-great-granddaughter of Elise Bouteiller. This has been in her family for more than 100 years, and I am very grateful to her for sharing it with me.

The Allen Loney family, with Elise as Virginia’s constant companion, crossed the Atlantic every year, and settled into a pattern: When in New York, they lived in the Gotham Hotel. In the summers, they visited Skaneateles; Virginia learned to swim in Skaneateles Lake.

For most of the year they lived in England, at Guilsborough House in Northampton, “the shire of spires and squires.” Riding cross-country from one church steeple to another — steeplechasing — was a popular pastime, as was the hunt: pursuing a fox over a less predictable course; Allen, Catherine and Virginia Loney all rode to the hounds. Allen had a stable of 25 horses, all hunters, three of which were Virginia’s.

In 1907, Alice Louise Loney died, leaving William Loney a widower for the second time.

:: The First American Formula One Champion ::

William’s grandson, David Loney Bruce-Brown, the younger son of Ruth, attended the Allen-Stephenson School in New York City, and then the Harstrom School in Norwalk, Connecticut, a prep school for Yale. But he was not cut out for academic pursuits. He instead showed an interest in auto racing, wrecking his mother’s Oldsmobile in 1906. It is possible that he caught the bug from his half-brother, George McKesson Brown, who that year purchased a Benz racing car and engaged a German driver, Karl Klaus Luttgen, to drive it in the Vanderbilt Cup race on Long Island.

By 1907, David Bruce-Brown had his very own Oldsmobile and won a race in it, catching the eye of Emanuele Cedrino, the manager of Fiat’s New York operations, who invited the young man to Daytona the following year for the speed trials on the beach.

In 1908, Matilda Wolfe Bruce died; she was the last of George Bruce’s children and left all to her grand-nieces and nephews: Catherine Wolfe Loney (Allen’s wife), George McKesson Brown, William Bruce Brown and David Loney Bruce Brown. (In 1910, the real property in the estate was auctioned off for $2,000,000.

David Loney Bruce-Brown in his Benz, outside his home in New York City

Now certain that college was irrelevant, David Bruce-Brown left prep school and made his way to New York and Emanuele Cedrino, who took him to Florida. When Ruth Bruce-Brown traced her son to Daytona Beach, she threatened the organizers with legal action. Those in charge agreed that David could stay and work as Cedrino’s mechanic but would not be allowed to drive. Which he did anyway, and promptly set a new world’s record for the flying mile. Cedrino had been right; the boy was born to go fast. His mother eventually relented, and David Bruce-Brown’s racing career began in earnest. He was a square jawed, muscular, handsome young man, and the public loved him.

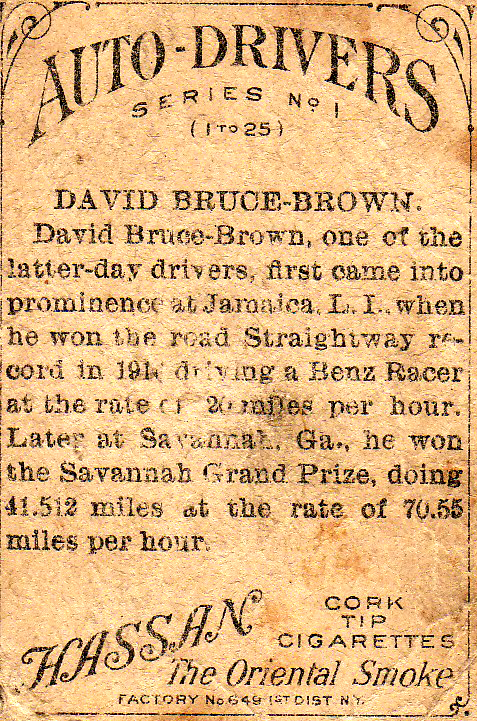

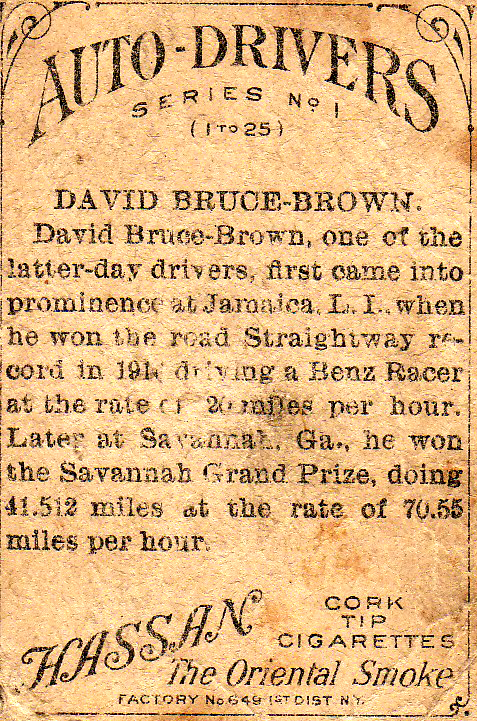

In 1909, he returned to Florida and set new records for the 1-mile and 10-mile runs. Also that year, he beat the legendary Ralph DePalma, who would later say that David was “one of the greatest drivers who ever-gripped a steering wheel.” In November of 1910, driving a Benz, David won his first American Grand Prize (Gran Prix), covering 415 miles in less than six hours on an open road course at Savannah, Georgia, defeating France’s Victor Hemery. The victory, in the words of the New York Times reporter, “only needed some sentimental happening like Brown’s mother rushing onto the track to kiss her victorious son’s grimy face to set the crowd perfectly wild.” And so it happened.

David Loney Bruce-Brown and his riding mechanic, Anthony Scudaleri, on their trading card

At the first Indianapolis 500 in 1911, Bruce-Brown drove for Fiat and finished third. Again in a Fiat, he won the 1911 American Grand Prize at Savannah, his second consecutive victory. With a Grand Prize win in 1912, he could retire the trophy.

David Bruce-Brown with his riding mechanic

In October of 1912, he prepared for his third American Grand Prize. Arriving at the Wauwatosa race course near Milwaukee, eager to practice, David ignored those who urged him to put on fresh tires, and roared out in pursuit of his teammate, “Terrible Teddy” Tetzlaff. On the open course, at 90 m.p.h., David’s left rear tire burst; the car swerved into a ditch and cartwheeled; the young driver and his riding mechanic, Antonio Scudelari, were hurled into the air and landed in a field. They were rushed to the hospital, but died. David Bruce-Brown’s fellow drivers stood in the corridor outside his room and wept.

Ruth Bruce-Brown had already boarded a train in New York to travel to Wisconsin; she would arrive to learn that her son was dead. Allen and Catherine Loney got the news by telegram as they were arriving at the Carlton Hotel in London.

In the New York Times, the race’s official starter, Fred Wagner, wrote:

“Every one connected with racing and many of the public at large were inexpressibly shocked over the lamentable death of David Bruce-Brown. This young driver was liked by all connected with automobiling… Mrs. Bruce-Brown will have at least one balm in her deep grief in the knowledge that her son was always a favorite and always was honest in his driving.”

An American sports writer said:

“As a racing driver, Bruce-Brown was looked upon as the best, not only in America but in the entire world. Built around a rugged framework were as stout a set of muscles as any athlete of his age and height could boast of, a fact which made the racing car more or less a plaything in his hands so far as guiding it on the highway.”

And a writer in England’s The Motor added:

“Bruce-Brown was typically American in his style of driving… a driver determined to get the most of it from beginning to end. But coupled with this wild dash was a consummate skill in the handling of his car, which is given to few men to possess… the extraordinary combination of wild fury and calm reasoning shown in every movement of the American driver.”

The family was plunged into mourning. Alice Louise Abbot, daughter of Harry S. and Alice Rebecca (Loney) Abbot, was to make her social debut that October in New York, introduced by her aunts, Mary Roosevelt and Ruth Bruce-Brown, but this was postponed until December.

In January of 1913, Alice’s engagement was announced at a luncheon at Sherry’s. The lucky lad was Clive Burlingame Meredith, a Harvard student from Cazenovia, New York. The engagement was expected to be a long one, but in October they eloped, motoring from the Abbot summer home in Skaneateles to Syracuse where they were married at the home of the Rev. Karl Schwartz, an Episcopal priest.

In 1914, William A. Loney, the family patriarch, died in Skaneateles at the age of 93. He was remembered as one of the Village’s most esteemed citizens. Funeral services were held at St. James’, and he was buried in the family plot in Lake View Cemetery.

:: The Lusitania ::

All of the Loneys had been accustomed to sailing to and from Europe, but the war in Europe brought that pleasure to a halt. Allen Loney, being an American, could have lived the life of an English country squire, uninterrupted, but he instead volunteered with the American Ambulance Corps, outfitting two of his cars as ambulances to evacuate the wounded from the front. In 1915, his wife Catherine chose to return to England from New York, so that she could work in a convalescent home for wounded soldiers.

Allen was nervous about Catherine and Virginia returning to England, so he sailed to New York where he joined them, and they all sailed together for England, aboard the Lusitania. It was known as the greyhound of the seas, a fast, beautiful boat that members of the family had sailed on before. Although a Cunard liner, it was under the control of the Admiralty and being used to ferry supplies and ammunition as well as passengers. The British felt it was nonetheless a civilian vessel; the Germans felt otherwise, and ran an ad in the New York newspapers warning American (neutral) passengers not to sail on British vessels. Most people ignored the warnings as propaganda.

On the voyage, Virginia was accompanied by Elise Bouteiller. Virginia was only 14, but she was a well educated, well traveled, confident and composed young woman, probably comfortable speaking French as well as English.

On May 7th, Virginia was resting in her cabin after lunch when the Lusitania was torpedoed by German submarine U-20. She rushed to the deck and found her parents. Her father, Allen, passed around life-belts, but did not keep one for himself. As the family stood on the deck, Allen saw a lifeboat about to be lowered with just one place left. He ordered Virginia to get in; she protested, but obeyed. As the lifeboat hit the water, it capsized, throwing everyone into the water.

Few women of the day knew how to swim, but Virginia had learned how in Skaneateles Lake. The Lusitania was sinking fast; the decks, usually six stories above the water, were swiftly drawing level. Virginia looked up and saw her parents, waving. She swam farther from the boat, but the suction of the sinking vessel drew her under. When she rose to the surface again, the Lusitania was gone; her parents were gone; Elise Bouteiller was gone. In the open ocean all around her, more than a thousand men, women and children were drowning. Virginia finally spotted a lifeboat that had stayed afloat, swam to it and was pulled aboard. When a sailor in the boat collapsed from exhaustion, Virginia took his oar and rowed with the other men.

When the survivors were picked up, Virginia was taken to London, and then went to Guilsborough House. The author Henry James, who was serving as the Chairman of the American Volunteer Motor Ambulance Corps at the time, wrote this of Allen Loney:

“He had been from the first one of the most ardent and active of our volunteers, friendly and devoted in every way, and sparing least of all his own splendid personal energy… He put at our disposal the passion of the born sportsman, but still beyond that an active human sympathy which rejoiced in helpful service and fellowship.”

Virginia passed a joyless 15th birthday in England, and then returned to the United States.

Virginia on the S.S. St. Paul, June 13, 1915, coming back to the United States from England; she has stitches in her chin, lip, cheeks and on the bridge of her nose, probably from cuts caused by debris in the water when the Lusitania sank

Virginia went first to the estate of her mother’s brother, George McKesson Brown. On his passport applications and customs forms, Uncle George listed himself as a “gentleman farmer.” His estate, West Neck Farms, was in Huntington, on the north shore of Long Island. The main house, designed by Clarence Luce, was in the style of a French chateau with towers and 40 rooms. There was a gatehouse, servants’ quarters, a stable, a garage and a boathouse where George docked his yacht and an 18-foot high speed runabout. George collected art and fine books, was a member of two yacht clubs and the New York Horticultural Society. He awoke every day to a lovely view.

The vista from George McKesson Brown’s main house (as seen today), with the boathouse in the foreground.

George assumed financial responsibility for his sister’s child, but her care soon shifted to Mary Bose Chamberlaine, a daughter of William Loney’s sister, Maria Loney Chamberlaine. Miss Chamberlaine had definite ideas about how a woman of Virginia’s position should be protected and prepared for her role in society, apparently not the job for Uncle George; Miss Chamberlaine was dismissive of Virginia’s four uncles and two aunts, “with none of whom she could live satisfactorily.”

:: The Heiress ::

Before the voyage, Virginia’s mother had drawn up a new will; Virginia received property worth $45,000, her mother’s jewelry, a $12,000 trust from a great-aunt, and an automobile. At 21, she would inherit her mother’s entire fortune, about $1,500,000, outright.

Mary Chamberlaine set up an apartment on Park Avenue, and went to court to see that Virginia’s needs were met. In her petition, in which she repeatedly referred to Virginia as “the infant,” Miss Chamberlaine asked for $25,500 yearly from the principal of her fortune to cover such items as rent ($5000), clothing ($3500), three servants and a personal maid ($1800), school, music and languages ($2500), summer vacation and travel ($2500), automobile and chauffeur ($2000), amusements, including horseback riding ($1500), and incidentals ($1000).

Miss Chamberlaine also requested her own income from the estate, explaining that she had been forced to leave her own home in Skaneateles, where she lived with her sister, and needed to outfit herself in the manner appropriate to the guardian of a young woman in society. Mary and Virginia were joined by Mary’s sister, Rebecca Chamberlaine Fabens, the widow of a Boston shipping magnate. One can only imagine what a change this was for Virginia: from riding to the hounds in England to becoming the ward of two spinsters in a Park Avenue apartment.

But not for long. In December of 1917, Virginia was engaged to Robert Howard Gamble, of Jacksonville, Florida, a naval aviator and Yale graduate. She was 16; he was 26. The two had met in Europe; they were married on April 27, 1918, at Virginia’s apartment at 840 Park Avenue, and left for Washington, D.C., and a home in Chevy Chase.

In 1921, at the age of 21, Virginia inherited $1,452,000 from her late mother’s estate. She and Gamble had two children, Robert Gamble Jr. and Catharine Gamble, but the marriage did not last.

The printed note on the back of this photo of Virginia, from the Bain News Service of New York reads, “Mrs. R.H. Gamble, N.Y. society, getting divorced, April 11, 1923”

In the spring of 1923, Virginia divorced her husband in Paris, and then returned with her children on the Aquitania. A few months later, Robert Gamble went to Huntington, New York, and spirited his children away to Jacksonville, Florida. Virginia reported them kidnapped. A custody agreement was eventually reached, and when Virginia married Paul Abbott, her ex-husband sent the children to the wedding. Virginia and her new husband honeymooned in Aiken, South Carolina, before returning home to Long Island. Virginia gave birth to a second son, Paul Abbott Jr., and settled into the life of a wealthy Long Island matron.

:: Epilogue ::

In 1916, Frederick Roosevelt, husband of Mary Loney Roosevelt, died at home in New York City. Ruth’s son, William Bruce-Brown, whose health had been troubled for years, died in 1918 at the age of 32.

In 1921, the George Bruce-Brown estate on Long Island was divided into 967 lots and auctioned off for $554,850. Ruth spent her time either in New York or in Europe; in 1921, she noted on her passport application that she was to visit France, Italy, Belgium, Switzerland, Holland and Spain.

Also in 1921, Alice Abbot Meredith, who had divorced her husband Clive “years ago,” married Alpheus Montague Geer Jr. in the orangery of the Garden Club, Pelham Bay Park. The bride was attended by her daughter, Mary Ruth Meredith (named for her aunts, Mary and Ruth), with Frederick and Henry Loney as ushers, and Virginia (Loney) Gamble holding ribbons with other guests to form an archway.

In 1927, Ruth Bruce-Brown died in New York at the age of 73.

In 1930, Henry Edward Loney died in Mountain Lakes, New Jersey.

Frederick Loney, William’s youngest son, had made his way in the world as an architect and then as a mortgage broker. Frederick married late in life, to a young woman from Australia named Margery Cummings, 21 years his junior. In 1934, he died, leaving his widow and a 5-year-old son, Frederick Loney Jr.

Virginia Loney Abbott, the little girl who learned to swim at her grandfather’s summer home in Skaneateles, died on April 4, 1975, in Southampton, New York, bringing to an end a remarkable family saga.

:: Memorials ::

At St. James’ Episcopal Church, Mary Norton Loney is remembered by a chalice and paten, donated in 1900. Alice Louisa Loney is remembered by a litany desk, donated in 1908. Maria Elizabeth Chamberlaine, William Loney’s sister, is remembered by a brass processional cross, donated in 1911. William Loney, who died in 1914, is remembered by a plaque on an endowed pew (#38), which also bears the name of its donor, his daughter, Ruth A. Bruce-Brown.

Alice Rebecca Loney, with her husband Harry Stephens Abbot and her brother, Frederick Roosevelt Loney on the porch at 103 E. Genesee

Alice Rebecca Loney, with her husband Harry Stephens Abbot and her brother, Frederick Roosevelt Loney on the porch at 103 E. Genesee

In July, prompted by

In July, prompted by