Hemlock Island by John Barrow

I have often thought the one thing Skaneateles Lake lacks, in order to be perfect, is an island. One too small to build on, but large enough to be scenic and inviting. And, actually, we once had one, Hemlock Island, at the south end of the lake. And on this island was an old growth forest, hemlock trees, hundreds of years old, up to 150 feet high, God’s own cathedral.

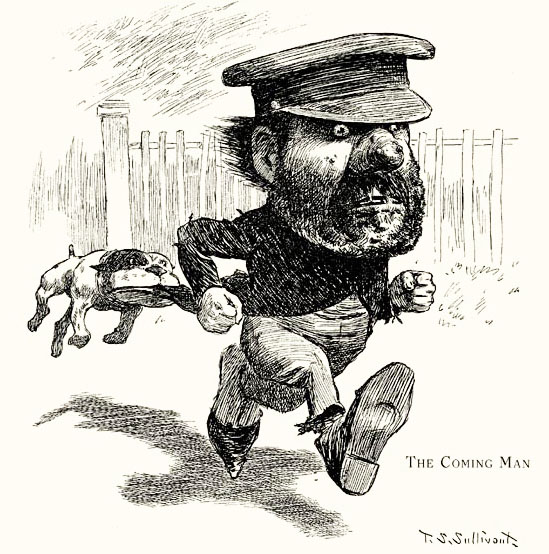

Hemlock Island sketched by the Rev. William Beauchamp

Hemlock Island sketched by the Rev. William Beauchamp

John Barrow painted it. The Rev. William Beauchamp sketched it. And people wrote about it. That’s a good thing, because otherwise, it’s gone.

The island began its life, it has been suggested, although we don’t have any first-person accounts, as an esker, a high ridge of sand and gravel left behind by a stream flowing from a retreating glacier. And when the water level of the lake was sufficiently high, the ridge was surrounded by water. We know that as early as the seventeenth century, hemlocks grew there, untroubled by man.

When Skaneateles was settled, people exploring the lake shore found an island with towering trees. Beauchamp sketched it in 1852, and John Barrow painted “Hemlock Island, Head of Skaneateles Lake” some time around 1860. When a catalog of Barrow’s paintings was prepared in 1908, Edmond Reuel Smith quoted William Cullen Bryant’s poem, “A Forest Hymn,” as a caption for the painting:

Father thy hand

Hath reared these venerable columns thou

Didst weave this verdant roof. Thou didst look down

Upon the naked earth, and forthwith rose

All these fair ranks of trees. They in thy sun

Budded and shook their green leaves in thy breeze,

And shot toward heaven. The century living crow

Whose birth was in their tops, grew old and died

Among their branches till at last they stood,

As now they stand, massy and tall, and dark,

Fit shrine for humble worshiper to hold

Communion with his maker.

Barrow, writing in 1897, mentioned a “Small Sketch of Hemlock Island” by Charles Loring Elliott, and with the advent of photography, a few photographs were taken. Even at a great distance, one can see the dark mass of trees, taller than those on the hillsides.

The south end of the lake; Hemlock Island is across the water, the dark ridge along the shoreline.

Hemlock Island can be seen through the lower right-hand windowpane.

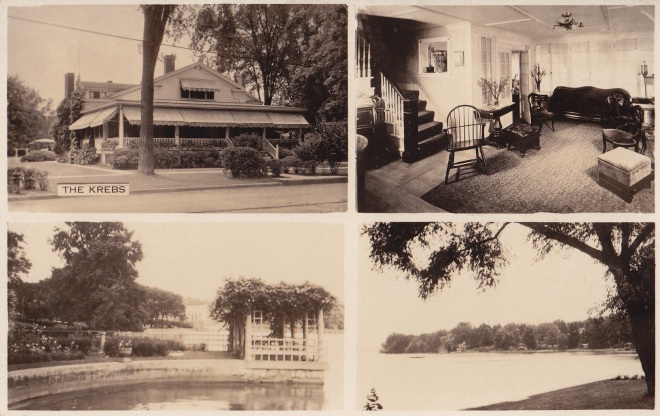

Beginning in 1847, when Glen Haven became a center for the water cure, Hemlock Island became a favorite place for visitors. A brochure for the Glen Haven Hotel noted, “At a short distance from the grounds is Hemlock Island – a delightfully cool retreat – densely shaded by trees and furnished with tables and rustic seats, for the benefit of picnic parties.”

A picnic on Hemlock Island, among the trees

The steamer Glen Haven at Glen Haven, with Hemlock Island in the background.

By the turn of the century, however, the island was somewhat the worse for its visitors. In 1902, John Barrow wrote, “Glen Haven Hotel in one form or another has had a prominent share in lake history… But I cannot help asking what has it done or what it ought to have done to save or restore the head of the lake. The wood below the hotel had never been thinned for two miles until near the shore they were cleared for about a mile, spoiling one of the most delightful walks and roads around the lake. The really magnificent Hemlock Island has been greatly despoiled and none may know what it was but those who remember it.”

But the greater despoiling was yet to come. In 1911, the City of Syracuse bought the Glen Haven Hotel and 150 acres of land, including Hemlock Island, for $40,000 to prevent further development and the contamination of the city of Syracuse’s water supply. The hotel and cottages were torn down and carried away. In 1913, students and professors from the New York State College of Forestry gave city officials a tour of the foot of Skaneateles Lake, including Hemlock Island, to show the results of two seasons of work, clearing brush, building trails, and studying the flora and fauna. They noted, “Nearly every tree native to the state and all the common and almost all the rare plants of the state, it was said, can be found on the property. The bird life is especially extensive.”

That same year, seeking some return on its investment, Syracuse estimated there was 600,000 feet of timber to be harvested on its property. But nothing further was done, until the Depression and the creation of the Civil Works Administration (CWA). President Franklin D. Roosevelt unveiled the CWA on November 8, 1933, using federal money to create local construction jobs, putting men to work on parks, roads, water mains and sewer systems. A project in Syracuse required lumber, and some city father recalled that the city owned a ready supply in Skaneateles. And so a crew of seven men, led by an experienced lumberman, were dispatched to Hemlock Island in January of 1934.

In March, a Syracuse newspaper reported:

In March, a Syracuse newspaper reported:

“Seventy of the towering trees which gave Hemlock Island its name have fallen, and the rest are marked to go, last of the mighty monarchs of the virgin forest at the south end of Skaneateles lake… The hemlocks of Hemlock Island are falling before the woodman’s ax, to make a CWA project and to supply lumber to be used by the city in shoring for construction of sewer and water trenches, at an estimated saving of $2,000 to Syracuse.”

So Syracuse saved $2,000, and the only old growth forest between the Catskills and the Adirondacks was lost forever. The article continued:

“On some of the trees are cut the initials of those who roamed the virgin forest of Hemlock island many years ago, when Glen Haven was there, long before Syracuse had taken Skaneateles lake for a water supply, and one of the earliest dates discovered is that of 1865. That tree has been marked to go. The king of the city’s forest on Hemlock Island that toppled to the ground and lies there today, waiting to go under the saw, was 150 feet high and 39 inches in diameter. It had 265 rings, a ring for each year it had been growing there, and this shows the tree was there on Hemlock island as early as 1669.

“More than a century before the beginning of the Revolutionary War it was there, 100 years before a white man ever set foot on the shore of Skaneateles lake. It was 125 years old when the first settler built his log cabin in the wilderness on the hill above the lake. It had been growing 50 years when Washington was born, and it was growing there—its heart sound to the core, and good for another 100 years—when it crashed to the ground on Hemlock Island this winter.”

Five days after the article ran, protests from Skaneateles and from Syracuse-based cottagers brought the cutting to a halt. That, and the fact that federal funding for the CWA ended at the end of March, saved a few trees. But Hemlock Island’s old growth forest was gone. And who do we have to credit for the loss? Let us remember Rolland Bristol Marvin, the mayor of Syracuse, and William W. Cronin, the city engineer, who from their desks thought of a way to save $2,000. The mayor’s spokesman noted, “While foresters have said the trees were old and their cutting was in accordance with forestry rules of practice, it was decided the pleas of the Skaneateles people that the remainder of the hemlock grove be preserved should be heeded.” The trees were old. Indeed.

* * *

In November of 1947, Elizabeth Barrow donated her father’s painting of Hemlock Island to the Skaneateles Library Association and its Barrow Gallery. My thanks to Bill Hecht, Bud Jermy, and Laurie Winship at the Skaneateles Historical Society, without whom I could not have written or illustrated this piece.

Accompanying Beauchamp’s drawing of Hemlock Island was this note written in 1882: “This sketch was made in 1852, & there has been little alteration since. The island is an elevated spot, surrounded by water & wet land. By it is found the large Limnaea stagnalis (the great pond snail) & also the yellow water lily.” The sketch is from Beauchamp’s Souvenirs of Some Early Days in Skaneateles, N.Y.