Month: September 2020

West Lake, 1949

Wallace & Norman’s Excellent Adventure

After returning from France at the end of World War I, Wallace Weeks went to work at the Oswego Falls Pulp & Paper Mills in Fulton, N.Y. The firm had been founded by his grandfather, Forest Weeks.

It was something of a family business; Wallace’s father, Charles G. Weeks, had been a Vice President of the Fulton mills and owner of the Skaneateles Paper Mills and the Lakeside Paper Mills before his untimely death in 1910.

Norman Scott was a salesman who sold screens to paper mills. In making paper from wood pulp, cellulose fibers suspended in water are poured over a sieve-like screen, laying down a sheet of interwoven fibers. As water is drained and pressed from the sheet, it becomes paper. Scott sold the necessary screens to paper mills; he was well known in the trade, and became known to Wallace Weeks. Both men were young and, in spite of Prohibition, appeared to enjoy a convivial cocktail.

Early on a Monday evening in June of 1922, they pulled up to the Great Northern Hotel in North Syracuse, lurched inside waving whiskey bottles, and said they were prepared to take orders for any quantity of “Syracuse-made Johnnie Walker, as per sample.” As they were being pushed back out the door, one of them added they had $6000 worth of dope in their car and were on their way to Watertown to sell it.

In an unkind twist of fate, State Troopers Merle Holmes and Phillip Sheridan were dining at the Great Northern that evening, witnessed the Weeks & Scott sales presentation, and rushed outside to stop the pair before they could drive away. The troopers seized the car—Wallace Weeks’ 1922 Buick roadster—and arrested them both. The local press sensed that this might be the arrest of the century: bootleggers with unlimited supplies, thousands of dollars in dope, the stuff law enforcement dreams are made of. And, getting a bit ahead of themselves, they said the car would be seized and sold at auction “to the highest bidder,” which is generally how auctions go.

After jailing the men for the night, and making a thorough search of the car (no dope), it became clear that these were not bootleggers or dope pushers, but just two yahoos who had been very, very drunk.

Tuesday morning, they were charged with violating the Volstead Act and reckless driving. Wallace Weeks, whose bail was posted by “a friend from Skaneateles,” had nothing to say and doubtlessly never wanted to be in the newspapers again.

Norman Scott, however, was just getting warmed up. On Tuesday he went to Watertown and registered at the Woodruff Hotel. He took Marguerite Crawford of that city to the nearby town of Carthage. At 4 a.m. on Wednesday, they rousted the county clerk out of bed to procure a marriage license and at 5 a.m. did the same for a Justice of the Peace, who married them, with some hastily summoned witnesses. At 10 a.m. the couple was back in Watertown to break the news to the bride’s parents, who told reporters they had never met Scott and had no idea how their daughter knew him. On Friday, the couple sped back to Syracuse for Scott’s court appearance where he pled “not guilty.” Back in Watertown that evening, he said that he did not wish to discuss what happened in North Syracuse. “That’s a closed chapter in my life,” he said, “all over with. It was all a mistake.”

County officials, meanwhile, sought the couple to question the legality of the marriage license. The bride gave her address as Carthage, but lived in Watertown. The groom gave his home as Montreal when getting the marriage license and as Springfield, Massachusetts, when checking into the hotel in Watertown. A reporter asked, “Where is your home?” And he replied, “I haven’t got any.”

Next stop, New York City, to continue the honeymoon. Without Wallace Weeks.

When the Waters Rose Up

A storm came up on Sunday morning, July 19, 1909. First darkening skies, approaching thunder and lightning, then a downpour with inch-wide hailstones and winds that whipped up waves on the lake. From the Packwood House, guests watched as an immense dark cloud formed over the lake and beneath it the water rose up 200 feet in a waterspout. The people “marveled and were awe-stricken.”

But they were not as awe-stricken as three boys on a sailboat off Mandana, who had been trying to reach shore since the first hints of the storm. The boat’s owner was young Sinclair Reynolds and his boat was the Lillian, named for his mother. His wide-eyed shipmates were Wallace Weeks, son of Charles Weeks, president of the Skaneateles Paper Company, and William Gray Jr., son of the paper mill’s Secretary.

The newspaper accounts said, “They saw the wind whip the water into a great fountain and then looked on with horror as they saw the demon-like thing tear toward them.” The spout lifted the boat out of the water, tossed the boys overboard and tore the craft to pieces. When the boys came up for air, only the hull remained; they swam to it and held on for 20 minutes until the steamer Glen Haven arrived—surely a welcome sight—and lifted them to safety.

The waterspout, meanwhile, proved to be just as adept on land as on water, heading east for three more miles to rip off roofs, demolish small buildings, uproot trees, tear a pump out of the ground with 30 feet of its pipe, and mow hay fields “as neatly as if the lot had been cleared with a fine tooth comb.”

Sinclair Reynolds lived to be 91. A life resident of Skaneateles, he was the son of attorney John Reynolds and Lillian Sinclair Reynolds. Lillian’s father was Francis Sinclair, founder of the Union Chair Works in Mottville where he manufactured his “Common Sense” chairs. Undeterred by the waterspout, Sinclair Reynolds was a charter member of the Skaneateles Sailing Club, which merged with the Skaneateles Country Club in 1933.

He was the owner and skipper of the legendary Laura, the Queen of the Lake since the 1800s, a sand-bagger sloop that carried 750 square feet of sail area and was unbeatable in a gale.

Wallace Weeks grew up in the Weeks House on Genesee Street, attended Dr. Holbrook’s Military School in Ossining, N.Y., and served as an officer in World War I. For a time he worked at the Oswego Falls Pulp and Paper Company, founded by his grandfather, Forrest Weeks, in Fulton, N.Y. In 1926, he patented the paper cap on the milk bottle with John Pease of the Netherland Dairy. In the 1930s, he moved to Poughkeepsie, N.Y., and died there in 1959.

William Gray Jr. spent just a few years in the village, arriving in 1908 and leaving in 1910 when his father took new employment. Although I imagine he never forgot his time here.

* * *

Photo: Waterspout off Martha’s Vineyard in 1896

The Packwood Diamond Heist

In July of 1892, diamonds disappeared from the Packwood House.

Mrs. Charles Stratton of New York City, a summer guest, discovered that a bracelet in her bureau drawer was missing nine diamonds, pried from their settings.

Theodore Specht, treasurer of the Glenside Woolen Mills and visiting from New York, was missing a diamond-studded horseshoe pin.

Onondaga County’s Criminal Deputy Sheriff John C. Kratz came from Syracuse, “questioned everybody about the hotel,” and left without making any arrests. The Auburn Bulletin noted, “The authorities say that no suspicious looking characters have been seen around the village and the hotel people say that they have entertained no questionable appearing people; hence the mystery.”

But the next week, Sheriff Kratz returned and “his presence excited the fear of the guilty one.” One Retta Allen, a head waitress at the Packwood since May, packed her trunk and rabbited, grabbing the 5 p.m. train to Auburn.

As if her unannounced flight was not enough to raise eyebrows, a woman answering her description had attempted to sell jewels in Auburn a few days before. The newspaper promised “a vigorous attempt will be made to fix the guilt of the robbery now that sufficient evidence has been gained to make an arrest.”

But crossing the line into Cayuga County, she moved beyond the jurisdiction of Sheriff Kratz, and sadly for us, beyond any further notice in the local newspapers.

The Muddle of Mills

Over the years, up and down Skaneateles Creek, mills opened and closed, owners changed, business names changed, hamlet names changed. A single mill might have different names and be listed in different locations without actually moving. As an amateur historian, I have found this to be very inconsiderate.

Take the mills of Thomas Morton. A native of Darvel, Ayrshire, Scotland, Morton owned two mills: The Mottville Woolen Company, in Mottville, and the Marysville Woolen Company, in Marysville, which was later known as Skaneateles Falls. But the Marysville mill was also known as the Darvel Mills. And when Thomas Morton sold the Marysville mill to his son, Gavin Morton, the mill was known for a time as the Ayrshire Mills (which later became the Waterbury Felt Company). That’s a lot of wool to unravel.

(A note: In other histories, you may read that these mills made fine cashmere. They did not. They made cassimere, a woolen, twill-weave, worsted suiting fabric.)

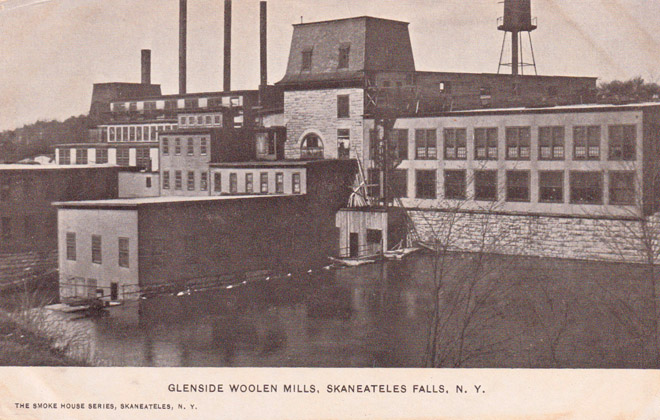

And then there’s this postcard. I couldn’t understand how such a massive building could escape my notice. Was this building in Glenside, Marysville, or Skaneateles Falls? Well, yes. And it began life as an iron works.

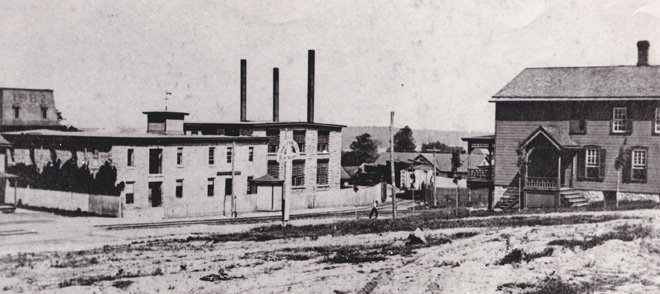

Riding the boom that came with the end of the Civil War, the Skaneateles Iron Works Company was incorporated in 1866 with $50,000 in capital stock; the principals were Henry Vary, Eben Bean, George H. Earll and Edward B. Coe. In December of ‘66, the ground was leveled in preparation for the erection of the buildings in the spring of ‘67.

The edifice of blue and gray limestone, and its equipment, cost $108,000. The site hosted a rolling mill, a forging shop, a machine shop, a “commercial room” for packing and shipping, and an office. The main business was the conversion of scrap iron into bolts, nuts, washers, rivets and spikes. The works were placed between Skaneateles Creek, a.k.a. the Outlet, and the railroad. The fast-flowing creek provided water power and the railroad enabled delivery of scrap iron and coal “without cartage.”

A new furnace was in operation in April of 1868; a month later, the rolling department was up and running. However, in June of 1869, the principals felt the need to raise an additional $150,000 and offered bonds that found few takers. Of the principals, Henry Vary died in 1870, missing what was to come. In February of 1871, Edward B. Coe was arrested for forging the names of George H. Earll and Charles Pardee on $18,000 worth of “commercial paper.” He admitted his guilt but said he would set things right within a few days. He did not. In his History of Skaneateles, Edmund Leslie wrote of Coe, “In his business operations he became involved in insurmountable difficulties which caused him the loss of all his property.”

Living on borrowed time, the Skaneateles Iron Works declared bankruptcy in February of 1873. In the autumn of 1873, a series of U.S. banks and railroads failed, tumbling like dominoes, and triggered the nationwide Panic of 1873, making things immeasurably more difficult for business. In Skaneateles, the third principal, Eben Bean, declared bankruptcy and left town.

The last man standing, George H. Earll—a prosperous dairy farmer, hop grower, distiller and paper manufacturer—had a fortune to fall back on, but he died in October of 1873, one month after the Panic began.

(An investor, Charles Pardee, lost $30,000, one of the reasons he cut his throat with a straight razor in 1878. Bankrupt and disgraced, Edward B. Coe left town in 1882 and took his own life the next year, leaping from a steamship off the coast of Oregon.)

Devoid of leadership, the Skaneateles Iron Works was auctioned off for $29,500 in 1874. It limped along under new management for two years. In February of 1876, an auction sale of “moveable property” was held by the Onondaga Savings Bank. In 1878, the bank sold the works to Archibald C. Powell of Syracuse for $5,500. Powell was a trustee of the bank and the superintendent of the Syracuse Salt Works, and under a legal cloud of his own. He held the Skaneateles property just long enough to sell some machines and move a few others to one of his operations in Syracuse.

In 1879, the property was bought by Howard Delano, Ezekiel B. Hoyt and Russell B. Wheeler, who had other businesses along the Outlet, and tended to them.

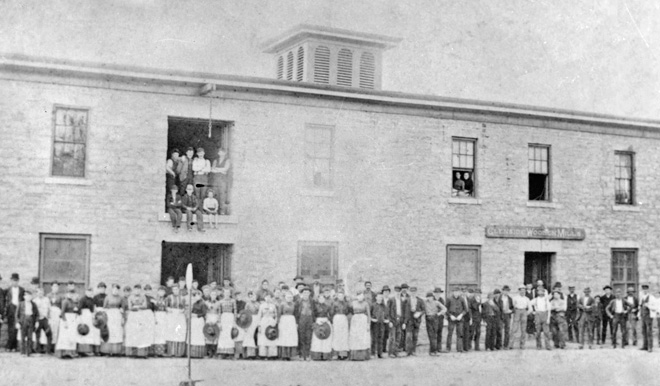

In August of 1881, James McLaughlin Jr. purchased the idle property for $4,000, and converted it into a woolen mill operated as “McLaughlin Brothers,” with his brother, John McLaughlin, as partner. The McLaughlin brothers were teasel merchants, and hence knew something about textiles.

The mill first produced woolen fabric for ladies’ goods, but soon turned to making coffin cloth, a plain-weave wool fabric dyed black for use as a pall over a casket, or as a casket lining. (To reach the proper funereal shade of black, the fabric had to be dyed five times. The spent dye was dumped into the creek every two hours.)

In September of 1888, “financial difficulties arose”—the McLaughlin partners owed the First National Bank of Auburn $189,000. The company was reorganized under the name of the Glenside Woolen Mills, with Theodore Specht of the New York firm Arnstaedt & Co., becoming the principal, investing $150,000 and gaining a controlling interest.

Theodore Specht was an importer and distributor of specialty cloths from Germany, and a U.S. woolen mill was a logical acquisition. For the first several years of Arnstaedt’s ownership, Specht continued to live in New York City. The McLaughlins retained stock; John McLaughlin continued at the mill and served as a Director. The Glenside Woolen Mills had something close to a monopoly on the coffin cloth business, employed 300 people, and made money.

When in Skaneateles, Specht stayed at the Packwood House. On July 4th, 1893, he sprang for the fireworks in what is now Clift Park, and in 1895, he gave out handsome prizes at the company picnic, honoring winners of the blue rock shoot (a.k.a. clay pigeon or trap shooting), throwing the hammer, and the footrace, as well as fine prizes for the young ladies’ contests. In 1899, he bought a house on East Genesee Street in the village, and in 1901 he and his family moved to Skaneateles from New York City. The Specht house became known as Hazelhurst (today’s Athenaeum). Specht bought more land, and had 20 acres in all, with a boathouse, an outdoor bowling alley and his own golf course.

In 1909, a downstream paper mill sued the Glenside Woolen Mill for polluting the water it used to make paper. The oil and grease from the wool was fouling its paper making machinery creating holes in the paper produced. The dye bleached out of rags was making it impossible for the mill to make white paper. At the end of the day, Glenside had to pay the paper mill $1,500 in damages and cease polluting the Outlet.

Also in 1909, growing competition and a glut of coffin cloth decreased dividends and prompted a five-year snit between James McLaughlin Jr. and Theodore Specht, as well as his son and son-in-law. The suit alleged that the Spechts diverted the mill’s income to Arnstaedt & Co.; it occupied the courts and enriched lawyers through 1914. James McLaughlin died before it was settled, but his brother John saw it through.

The onset of World War I in Europe complicated matters, as the company’s aniline dyes were made in Germany and could no longer be imported; the mill had enough dye for just four months. At the same time, “war orders” for uniform cloth swelled the mill’s volume. In 1915, a fire at the mill destroyed a carding machine that had been made in England and threatened to idle 250 workers for four months. In November of 1916, Theodore Specht died, and ownership of the mill passed to his son, Harry Mortimer Specht. All in all, it was a bumpy ride.

Branching out in the 1920s, the mill began making automobile upholstery. From 1923, Glenside produced most of the cloth used by the Franklin Automobile Company of Syracuse, and supplied other automobile manufacturers as well. But the Stock Market Crash of 1929 and the ensuing Great Depression took their toll. The Franklin company went out of business in 1934 and in July of 1937, the Glenside Woolen Mills shut down while “reorganizing.”

In 1939, the mill attempted again to reorganize and start work, hoping to employ 75 workers. In 1940, with World War II on the horizon, orders for wool cloth to produce U.S. Army, Navy and Coast Guard uniforms kept the business afloat for a few more years.

In 1951, the idle Glenside Woolen Mill was purchased by Welch-Allyn, a manufacturer of diagnostic medical instruments, which moved its operation from Clark Street in Auburn to Skaneateles Falls. The company expanded and modified the building many times over the years. In the summer of 2014, Welch Allyn enlarged its Jordan Road facility, just north of the Village, and moved operations to the new space, emptying the former Glenside Woolen Mill building. Now known as Eco Park, the building is occupied by Kohilo Wind, a maker of vertical axis wind turbines, as well as Lilypad Cosmetics and Scratch Farmhouse Catering.

The west side of the original mill is almost entirely obscured by a forest that has grown up over the past 150 years, but one can still see the placement of the windows and doors of the original Glenside Woolen Mill in part of the present-day building facing east.