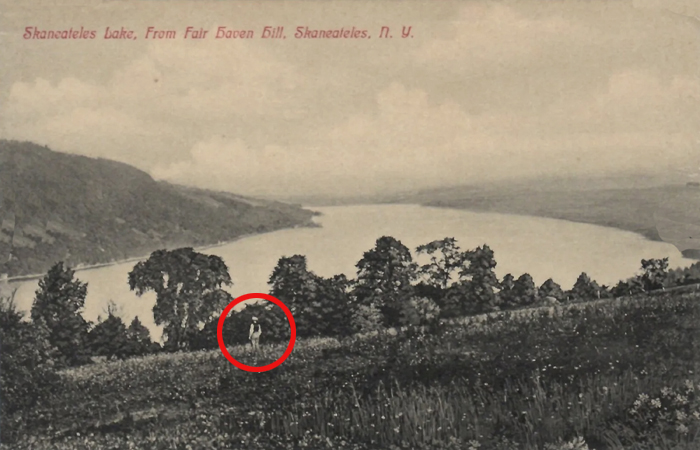

One thing I’ve noticed in creating images for the Creamery’s “Big Screen” continuous video display is the occasional appearance of early photo bombers:

One thing I’ve noticed in creating images for the Creamery’s “Big Screen” continuous video display is the occasional appearance of early photo bombers:

An early photo of members of Skaneateles High School’s Class of 1913.

Top Row: Russell De Witt, Frank Harse, Russell Manley, Sinclair Reynolds, Bill Ludington

Third Row: Elizabeth Lawton, Bessie Donovan, Jessie Oughterson, Ethel Harse, Caroline Rickard, Mabel Shultz, Gertrude Palmer, Stella Zimmer, Anita Ludington

Second Row: Hester Tilley, Edna Ruth, Marg O’Hara, Lucybelle Fibbon, Lillian O’Hara, Ethel Jenks, Hazel Gunsalus, Tessie Russell, Valerie Ebbetts, Adele Holben

Front Row: Thomas Durkin, Harold Barber, Holdredge Sinclair, Bill Treen, Harold Loss, Lawrence Whiting, Garret Murphy, Arthur Spearing

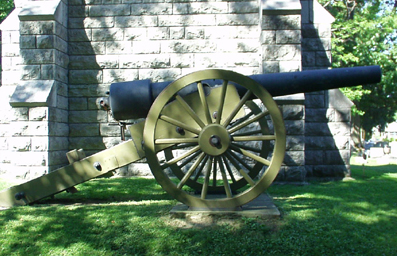

They rest on either side of the Soldiers and Sailors Monument like decorative bookends, and you would hardly know in passing what remarkable instruments of war they were. They arrived in the Village on August 13, 1897, two years after the completion of the monument. They were a gift of the federal government, with the freight ($39.40) paid by the local Grand Army of the Republic (G.A.R.) post.

They were first placed on limestone stands to match the monument; in 1995 they were mounted on authentic wheeled carriages built by Tom Dean and Charlie Rounds of our village.

Specifically, our resident cannons are 30-pound Parrott Guns. The barrel of each gun is 11 feet long and weighs 4,200 pounds. Too heavy to be moved during a battle (each requires a team of eight horses), these were siege guns, wheeled into emplacements and brought to bear on fortifications. The 30-pound Parrott Gun was used by Union armies to besiege Confederate forts and fortified cities across the south, most famously at Vicksburg, Mississippi; Port Hudson, Louisiana; and Fort Macon, North Carolina.

They take their name from their inventor and manufacturer, Robert Parker Parrott, the superintendent of the West Point Foundry from 1836 to 1867. Our two cannons were made there, just across the Hudson River from West Point, in a cluster of brick buildings whose fires glowed red through every day and night of the Civil War. You can see the identifying initials RPP and WPF engraved on the muzzle face of each gun.

Even without the initials, the Parrott gun is easily recognized by the thick band of iron wrapped around its breech. This reinforcing band, at the point of greatest force, enabled the gun to be made of iron, rather than bronze. The Parrott Gun could thus be manufactured quickly and cheaply. It was a boon to the Union.

Parrott Guns were also known as Parrott Rifles because of their rifled bore, five grooves running the length of the barrel with a right-hand twist. The grooves spun the projectile so it flew with a spiral motion, traveling farther and hitting the target with more power and accuracy.

The “30-pound” designation refers to the weight of the projectile the gun fired. The West Point Foundry made 10-, 20- and 30-pound Parrotts. The 30-pound Parrott fired two kinds of shells, each about 4 inches in diameter and 10-12 inches in length. One type was 30 pounds of solid iron and was known as a “bolt.” The second type was hollow and packed with a matrix of black powder and lead balls, called case-shot. A fuse exploded the case-shot in the air or on impact. The solid bolt was used to destroy walls and other artillery pieces. Case-shot was intended for gun crews and troops.

Fully elevated, the 30-pound Parrott Gun could send a projectile almost four miles. Upon its return to earth, the 30-pound shell could pass through masonry walls, even solid stone. And the gun was accurate. At a range of a mile and a half, gunners could place three out of four shells within ten feet of their intended target. As the Confederacy learned in North Carolina.

The siege of Fort Macon, a coastal fort on the Outer Banks, had been dragging on for more than a month when the Union artillery arrived for the final assault. Most notably, three 30-pound Parrott Guns were emplaced a mile from the fort’s outer walls. On April 26th, 1862, the Union guns opened fire and the Confederate guns returned the barrage. Early in the day, the rounds from the Parrotts were carrying over the fort, but by noon they had found their range. A single round hit three of the fort’s largest guns in succession, knocking two out of action, killing three men and wounding five more. The parapets were soon swept clear. Shot passed through solid stone stairways and masonry walls, wounding men inside.

Because the fort had been built by the Union, the Parrott gunners knew the exact location of the powder magazine. They began concentrating fire on the wall that shielded 10,000 pounds of gunpowder. When it began to crumble, the fort’s commander, Col. Moses White, realized he was one round away from leading a band of angels. The white flag went up and the age of masonry fortifications came to a end.

Today you can buy Parrott shells dug up from the mud of Vicksburg, Port Hudson and the Carolina coast. You can see Parrott guns in parks and battlefields. Of the 30-pound Parrotts, 198 are known to survive. Two sit quietly in Lake View Cemetery. I don’t know where they’ve been, or what they’ve done. But I know what they were capable of, and I look on them with respect.

* * *

“Parrott Guns,” Chelsea Telegraph and Pioneer, October 3, 1863; “The Confederate Defense of Fort Macon,” Paul Branch, Ramparts, Spring 2001; Union Drummer Boy Civil War Artifacts; “The Patriot and The Parrott Rifle,” Eric Ortner; The Encyclopedia of Civil War Artillery. My thanks as always to the Skaneateles Historical Society, and to Tristan Whitehouse for holding the other end of the tape measure.

First posted in 2009, this piece has been updated with new information to accompany the revised version of the Soldiers and Sailors Monument posting.

Built in fits and starts, of limestone and marble, and crowned with bronze, the Soldiers and Sailors Monument stands today in Lake View Cemetery to remind us of hundreds of young men who marched south to do battle so that the United States might remain united. But as the war was a struggle, so too was finding a proper way to remember it.

Twenty years after the end of the War of Rebellion, the Town of Skaneateles still had no monument to its heroes. Such memorials were being raised all over the north, the effort usually led by the Grand Army of the Republic (G.A.R.), an organization of Civil War veterans established in 1866. Each town’s G.A.R. post was named after a Civil War hero, and given a number. The Skaneateles chapter was chartered in 1880, Ben H. Porter Post 164, and led the local efforts to honor those who served, first raising funds in February of 1886.

But just as the honorees of the monument had endured shot and shell, so its promoters would have to endure politics, poverty and letters to the editor.

The first wrinkle came in June 1886 when a rival association, “The Soldiers’ Monument Association of Skaneateles,” began collecting for a monument to honor veterans of the Revolutionary War, the War of 1812, the Mexican War and the Civil War, plus, in a sweeping catch-all, any soldier in the town or adjoining towns who made a contribution to the fund. By October, that association had collected $394. In December of 1887, however, under-financed and under-appreciated, they bowed out. The following month, the G.A.R. noted that $936.10 had been raised and work would begin.

In December of 1888, a site was staked out in Lake View Cemetery. Stone arrived in January of 1889. In the spring, local stone mason William Cottle began laying the foundation.

As befits a war memorial, sniping began at once. One critic pointed out that the monument was being built on quicksand. Cottle replied that six feet of foundation stone would be laid on four thicknesses of plank, and would hold up quite well. And to his reply he added this verse:

“Rock, sand and timberland

Are what I like to see.

But from big guns and fools’ tongues

Good Lord, deliver me.”

Cottle finished the foundation in August of 1889 and began work on the first level. At summer’s end, the monument stood 16 feet high but alas the treasury had dwindled to nothing. No work was done in 1890. In 1891, the coffers held one dollar and eleven cents. In early 1893, the unfinished monument was scorned as an “unsightly pile of stone.”

But in September of that year, Cottle returned to work on the second story. The expenses were “to be borne by a liberal citizen of the Village” who guaranteed the monument’s completion. Cottle finished the work using 240 tons of limestone in all, and the monument stood 60 feet high. On its front, an inscription read, “In Memory of the Soldiers and Sailors of Skaneateles.”

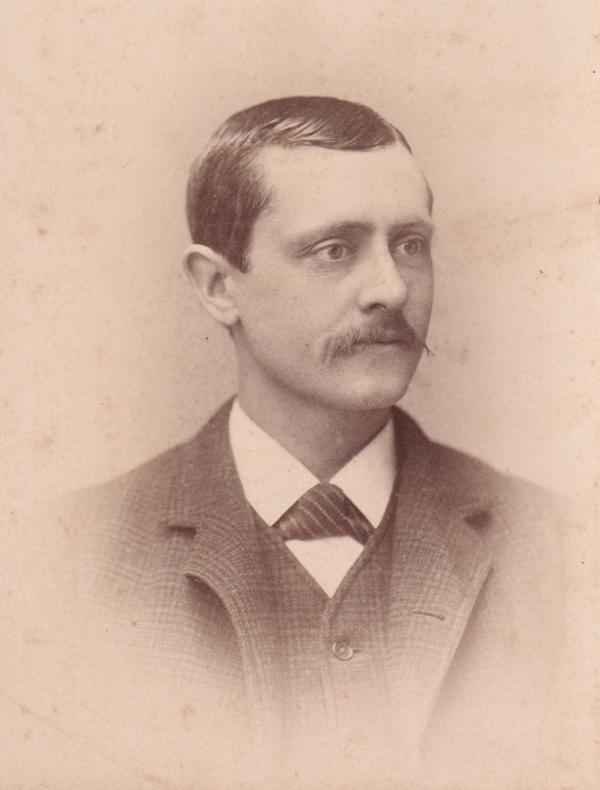

The “liberal citizen” was artist, banker and civic leader John D. Barrow, the designer of the monument, of whom it was said, “he did not have a warlike spirit, but he was a friend of the soldier himself.”

To crown the spire, a statue was suggested, and more money was sought. By January of 1894, $1048.20 had been raised and a $950 bronze was ordered, also to be designed by Barrow. His finished design was cast by Melzar Hunt Mosman (1846-1926). In addition to our statue, Mosman also cast the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument in Bridgeport, Connecticut; an 8-ton equestrian statue of General Ulysses S. Grant for Lincoln Park, Chicago; the bronze doors of the U.S. House of Representatives; and the Tenth Massachusetts Regiment monument at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

By October of 1894, Barrow’s statue of a Union soldier had been delivered and installed, raised to the top by William Cottle, and unnamed horse, and a block & tackle. But on windy days, the statue rocked. Word was sent to its makers “to come and remedy the difficulty.” In the summer of 1895, the statue was steadied with two bolts securing a strap over one of the figure’s shoes. Wind was not the only culprit, as gusts of irate letters buffeted the monument as well. Wrote one curmudgeon, “I think the statue is too far away. We haven’t all got spy glasses.”

In June of 1895, the names of 204 of the Town’s enlistees were carved on slabs of marble and mounted inside the monument, on the east wall. On the west wall, three more panels carry the names of 147 more soldiers. There is a story in every name: Navy Lt. Benjamin Porter, 20, killed leading a charge across the beach at the storming of Fort Fisher, North Carolina. His brother, Private Stanley Porter, 20, mortally wounded at the Second Battle of Bull Run, Virginia, his body never found. Private Albert De Cost Burnett, 16, the Village’s youngest recruit, dying of disease at Harrison’s Landing, Virginia. Private Wadsworth B. Francis, 51, killed at the storming of the fortress at Port Hudson, Louisiana. Sgt. James Dunn and Private Michael Dunn, dying at Andersonville Prison, Georgia. In all, 60 men belonging to the Town of Skaneateles gave their lives in the conflict.

The completed Soldiers and Sailors Monument was dedicated on September 4, 1895. The effort had taken almost 10 years and $10,000, but a throng of 8,000 crowded the Village for the dedication, and was well pleased.

Today, atop the monument, the silent soldier still speaks about his designer, the “unwarlike” John Barrow. Take a look and see what the soldier is not doing. He is not aiming or firing his weapon, not charging into eternity, or standing guard, or dying, unlike so many memorial figures of the era. This is not a statue about war. The soldier’s rifle stands at his side, steadied casually by his right hand, as if it were a walking stick. The rifle’s bayonet is tucked in his belt. The soldier’s left hand is empty and hangs relaxed at his side. His forward foot is almost off the pediment, as if he is preparing to move on. His jaw is firm, his eyes are steady, and he looks straight ahead, calmly, resolutely. The battle is over. The war is done. Peace beckons on the horizon.

***

Notes

First posted in 2009, this piece has been updated with new information and photos.

The last surviving member of Ben H. Porter Post, No. 164, G.A.R., was John Thompson. Enlisting as a private in February of 1865 at Auburn, he was present when Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox Court House in Virginia. Thompson died at the age of 92 on March 9, 1939.

The photo of the monument is most likely William Cottle’s own, found in a Cottle family attic in Maine.

The photo of young William Cottle was donated to the Skaneateles Historical Society by members of the Cottle family.

The photo of Barrow’s statue was taken by Matt Champlin, via drone, and we are very grateful to him.

“One can easily make the trip from this village to Glen Haven and return the same day, by taking the 8:03 a.m. train, reaching Skaneateles at 11:15, and Glen Haven at one o’clock. Returning he will be in Skaneateles at 5 p.m., with a little time to spare, and in Syracuse soon enough for our evening train. This arrangement, having no long delay at Skaneateles Junction, holds good for every day but Saturday.

“We reached the pretty village in due season, but did not leave at once. There were some calls to make, some provisioning to be done, and it was nearly 3 p.m. when our two boats were off for a camp far up the lake. ‘Auld lang syne’ and a good recommendation had brought us to [John B.] Marshall’s store, where the late popular postmaster deals out the choicest wares to housekeepers and campers, and the recommendation held good. This is one prime requisite of a successful camp, for it is no joke to have poor articles when far away in the woods. As for the boats, one was a handsome yawl, carrying two of our party, and most of our luggage; the other was a paper canoe, in which the writer was deposited. A paper boat ought to be good enough for a literary man, but there is little chance to spread himself. In fact, it was soon evident that canoes were meant for Indians, and that for rowing in one a primitive costume was best of all. When this fact was learned and acted upon, the little craft easily made good time over the waters.

“In the shadow of the high rocks near Fall Brook we glided along late in the afternoon, and a little before seven friendly voices invited us to ‘come ashore, and set up shop,’ on Pray’s Point, eleven miles up the lake. It was a goodly spot, where the steamboat touched daily, but four miles from Glen Haven, with a fine spring, and an ample beach. Moreover there was a colony of summer cottages not far off, where Prof. [Robert Bruce] White, of Syracuse, and sundry relatives, spend the summer months. Back of the point was a romantic glen, with waterfalls and precipices, and near by were many spots attractive to the naturalist and artist. So we ‘set up shop.’

“The great advantage of the west shore of the lake is that by the middle of the afternoon one can row or ramble along the bank in the shade, while the eastern shore lies in the full light of the sun. Above and below Fall Brook, under the high and picturesque rocks, this is delightful. The rocks are brightened with drooping or tufted ferns, and there are dark recesses, and picturesque battlements, and detached masses of curious forms. Against their base sleep or break the crystal waters of the lake. Beautifully clear those waters are, very different from those of a flowing river. But, on the other hand, they afford little food for water life, whether it be that of fish, shellfish or plant. No water lilies bloom on the surface, no curious shells are seen in the depths, no turtles enjoy the heat of the sun.

“Our camping ground had a good name, for it was called Pray’s Point. Should the name survive, some future scientist will make a myth or a legend out it, after the fashion of his race, ignoring the worthy old farmer after whom it was named. It used to be known, too, as Elm Tree Point, from the majestic tree which was conspicuous from every point of view. But the present name is old. In the chronicle of an early voyage in 1846, by the Rev. Dr. [Joseph Morison] Clarke, of Syracuse, it is said, ‘And when they had sailed a mile they came to Sycamore Point, otherwise called Pray’s Point from its owner’s name; and there they tarried a little space.’ It has changed since then. There is a croquet ground for diversion, and a reservoir in the rock for the spring, and a grotto behind it to receive butter and milk, and it has many little conveniences which residence suggests.

“The full moon brightened our camp that night, and the rippling lake danced in its light, but men must sleep even amid so much that is beautiful, so we lost a great deal of poetry in the necessary prose. It is astonishing how people will sleep in spite of the oldest proverbs; that is, at unseasonable hours. It seemed incumbent on me to set a wise example, and to follow Poor Richard’s advice. So the little canoe crossed the lake before sunrise next morning, explored the rocky shore, landed at cottages and tents, and found all asleep. One would have thought that the sage and athletic Prof. B. would have been ‘Early to bed, and early to rise,’ but the card I pinned to a tree was dated at 6 a.m., and not a soul stirring. Shall I say that the Rev. Dr. C. was just as bad, and that the spots on the sun had to wait for his awakening? But then all was quiet at our camp, too, when the canoe returned, and we breakfasted at very fashionable hours. Had we not come for rest, as well as recreation?

“Glen Haven was just far enough for a pleasant excursion, which was made several times. It had quite a busy aspect with its cottages and new hotel. On the other shore were pretty houses, where the steamboat landed daily; but for the most part I took to the rocks and ravines. How beautiful are some of those ravines, with their picturesque rocks and many cascades. One wants rainy weather for the latter, however, and our great blessing was that not a drop of rain fell. So we went when and where we pleased. In several spots on either shore we found the rare Slender Cliff Brake growing plentifully, and in one ravine discovered the Walking Fern quite out of its proper sphere. Then the Double-toothed Snail was frequently seen, and on ledges and in crevices of rocks appeared the neat, mossy nests of the Phoebe-bird. On the fallen mass on the east shore, known as Artist’s Rock, two of our lady visitors perched themselves where I had sketched an artist friend thirty years before. At Cold Spring, they endeavored, with much laughter, to drink of the water which gushed from the rocks. In default of modern china, some linden leaves at last made useful cups.

“The ravine back of our tent was very picturesque, but at the next point south both rocks and waterfall were very fine indeed. No lack of cascades is there anywhere, provided water can be had. Ravines are many in number and each one has its picturesque series. In such places, too, the geologist finds use for hammer and chisel; in fact for brains, too, for many are the problems that await him. And if one is lazily disposed he can lie under a tree and read, free from the annoyance of insects, and lift his eyes quietly at times, to take in the beautiful scene before him.”

B.

— The Baldwinsville Gazette and Farmers’ Journal, August 6, 1885

I am guessing that “B.” is William Beauchamp. And this passage that follows, written nine years earlier, adds to the story:

“I have, however, a journal in Biblical style, written in 1846, by my old friend, the Rev. Joseph M. Clarke of a trip made that year by a party of five to the head of the lake. Two of these started after the rest, and in the night saw the distant camp fire while delayed by an adverse wind. So ‘they took courage and some biscuits,’ and sailed on. At the camp they ‘spread a table in the wilderness. And they had buffalo skins for couches, and towels they had for table cloths, and they had water from a living spring, and the food came from well filled baskets. And in their journeyings they did eat bread and flesh in the morning, and flesh and bread in the evening, and at noon they did likewise; and for lunch they had gingerbread. And they drank coffee in the morning, and tea in the evening, and at noon made lemonade.’ This was early camp life.

“They sailed home ‘in a violent calm… after a perilous voyage of three nights and four days.’ How often we ‘scratched at the mast,’ or ‘whistled for a wind’ in these long calms.”

— William M. Beauchamp in “Notes of Other Days in Skaneateles,” written for the Skaneateles Democrat in 1876, published again in the Annual Volume of the Onondaga Historical Association, 1914.

News from November 28, 1911:

“This must be an ‘open’ season for muskrats. One of our citizens going to business about 6:30

Saturday morning was met just east of the post office on Genesee St. by an animal that at a casual first glance he thought might be a cat but after it had dived through the iron fence in front of Gen. Ludington’s residence and commenced to scuttle along the yard to the rear of the house he plainly made it out to be a muskrat. It’s tracks were plainly seen in the newly fallen snow around the front and side of the Shear block.”

For those who do not recall where everything was in 1911, today the muskrat would have been sighted just east of S.J. Moore Jewelers, in front of the Elephant & the Dove, and it would have dived through a fence in front of the Skaneateles Masonic Lodge #522.

With thanks to Bill Davis and Tyde Richards

Photos of the low lake level in November of 1965, with thanks to Bill Davis and Tyde Richards, with a shout-out to “WALt” who tagged the wall above the dam. One wonders who and where he is now, and if he will ever know his name has gained a very small measure of Internet immortality.