Month: August 2013

Jubilee Choirs in Skaneateles

At the end of the Civil War, the number of newly freed slaves in the U.S. was estimated at almost four million. Because the established schools and colleges of the nation were not inclined to throw open their doors to these new citizens, thoughtful individuals began creating schools especially for them.

Fisk University opened in Nashville in 1866, the first U.S. university to offer a liberal arts education to “young men and women irrespective of color.” But five years later the school was in financial difficulties. In 1871, George White, the school’s treasurer and music professor, created a choir of Fisk students and took them on tour to raise money for the school. Their early performances were met with “surprise, curiosity and some hostility” as these young singers who did not deliver the expected minstrel performance. But eventually their talent, dignity and persistence prevailed. And their success inspired legions of imitators, some from schools, others with a more commercial agenda — so many “jubilee singers” in fact that promoters went to great pains to assure the public that their particular troupe of singers was “genuine.”

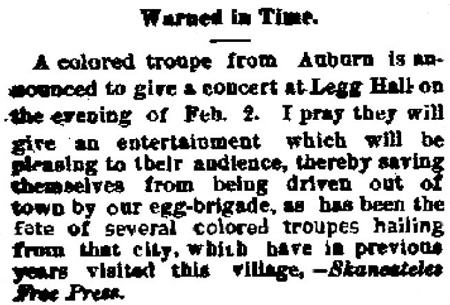

Skaneateles hosted many of these choirs. The reception accorded the first few did not reflect well on the village. In January of 1884, the Skaneateles Free Press ran this article:

In October of that year, the New Orleans University Jubilee Singers, “composed entirely of colored people,” appeared at Legg Hall. (New Orleans University was a historically black college founded in 1873.) You have to give the singers credit for courage, and the lack of newspaper accounts suggests that the village behaved itself.

In October of 1887 and again in January of 1888, the Centennial Jubilee Singers of Storer College sang at Legg Hall. The first concert was to raise money for the college’s “Girl’s Boarding Hall” at Harper’s Ferry, and the second benefited both the college and the Skaneateles Fire Department. The troupe’s reviews from other towns glowed with praise:

“We have no hesitation in saying that they sing the religious melodies and hymns of the Southern Negro population with astonishing effect, and in a manner to challenge attention. Without doubt the alto of the troupe [Miss M.E. Dixon] could distinctly sustain her part alone in a chorus of five thousand voices.” — The Boston Herald

“One could listen hours to those rich, mellow voices with a restful pleasure which Trovatore or Tannhauser does not give. Their voices are evenly balanced and in perfect accord for concert singing. The opening chant showed what they could do; this was rendered with an expression which many a cultivated church choir might envy. Miss Dixon has a pure alto voice, of such power as to be almost phenomenal.” – The Portland [Maine] Daily Advertiser

The Fisk Jubilee Singers, circa 1885

In March of 1891, and again in March of 1895, the Fisk Jubilee Singers, from the Fisk University of Nashville, performed to a full house at the Skaneateles Library, upstairs in “Library Hall,” to benefit both Fisk and the library. The group was already world famous, having performed at the White House for President U.S. Grant (in 1872) and President Chester Arthur (in 1882), toured Europe and performed for Queen Victoria (in 1873). (In their second visit to Washington, the choir could not get a hotel room, but their singing of “Safe in the Arms of Jesus” at the White House moved President Arthur to tears.)

In 1893, the New Orleans University Jubilee Singers returned to Skaneateles, and the newspaper assured the public that, “The great attraction of the New Orleans Jubilee Singers is that they sing the genuine negro melodies in the genuine negro manner.”

In 1898, the Claflin University Quintette, of Orangeburg, South Carolina, performed at the Methodist church, and the Rev. L. S. Boyd afterwards noted:

“The Claflin Quintette sang here last night to the expressed delight of a packed house. It is asserted on every hand this morning that if these young men were to appear here again, no building in town could hold the audience. The boys are intelligent and cultured, and any house which entertains them will do itself a favor. I am pleased to give them unstinted commendation.”

In September of 1898, J.K. Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin Co. brought its show to Legg Hall, and one of its attractions was “the original and justly famous South Carolina Jubilee Choir composed of genuine southern darkies.” The editor of the newspaper, in the grip of some incomprehensible compulsion, continued, “To secure this attraction it was necessary to exercise a great amount of tact and diplomacy, as the true Southern darkie has a horror of being brought into notoriety or being placed in public places or made the least bit conspicuous. They claim they were aired enough during the great war on their behalf.”

In 1900, the Methodist church hosted the Thomas & Tucker Jubilee Singers, a group noted in history as having included Noble Sissle, the pioneering American jazz composer, lyricist, bandleader, singer and playwright who penned “I’m Just Wild About Harry” with Eubie Blake, and the musical Shuffle Along that ran on Broadway for more than 500 performances.

In 1907, the Orpheus Jubilee Singers performed in Skaneateles at the Methodist church. Of the group, it was said that Maude Browne, a soprano, had a voice “rich, rare and full of sweetness of quality,” and that the singers had the good taste to preserve the traditions and simple beauty of their songs and “to perpetuate no travesty on the work.”

In 1914, the Mason Jubilee Singers, a “famous colored company,” appeared at the Methodist church with a program of “Negro Life in Song and Story, Plantation Melodies and Old Folks Songs.” The next year they sang in Marcellus, where the Marcellus Observer delivered this bizarre, left-handed compliment, “You have heard a ‘culled pusson’ sing. Their voices find close harmonies not found on piano keys. A genuine southern darkie is always interesting. Add to that training, ability, stage experience, the attraction becomes greater.”

In May of 1925, the Methodist church hosted the Peerless Jubilee Singers , a quartet. They had recently sung at Cornell University, and the Cornell Sun reported:

“They give the concert In two parts. The first section will consist of songs of the days gone by. Among these, the artists will sing ‘Swanee River,’ ‘Go Down Moses,’ ‘Hand Me Down,’ and a number of others. The second part will open with a chorus ‘By the Waters of Minnetonka.’ This section of the program will be devoted almost entirely to solos by various members of the troop. They will close with ‘II Trovatore’ by Verdi.”

One can see the “Jubilee” repertoire expanding, and journalism crawling forward into the 20th century, at least in Ithaca.

Of the groups who sang here, the Fisk Jubilee Singers continue to perform.

Bird Sanctuary

Every working day for 15 years, walking past this derelict gas station east of the Village gates on Route 20, I have thought of it as an eyesore, a monument to sloth and decay. But this afternoon, I discovered something that summoned a childhood memory and changed my perception. I grew up in Kenmore, a suburb of Buffalo, and when I was young, the city of Buffalo was improving its streets. Rail traffic was getting lighter, car traffic heavier, and so the city removed a number of viaducts, iron bridges, where unused rail lines passed over dips in the road, and widened the roads. No one realized, at the time, that because the viaducts were home to thousands of pigeons, that the birds would have to find new homes. And so it was one day that my mother was shocked to see urban pigeons at her suburban bird feeder. Even the birds were participating in urban flight.

Clearly, they had to go somewhere. And that brings me back to the abandoned gas station on Route 20. Today I discovered that there is a family of pigeons living under the eaves. I watched Mr. and Mrs. Pigeon coming and going, using the wire at the building’s northeast corner as a front porch. This is not an eyesore; it’s a bird sanctuary. I feel much better about it now.

Above, Mr. & Mrs. Pigeon on their front porch.

The McGibney Family

In March of 1881, Legg Hall hosted a concert by the McGibney family of singers and musicians. James B. McGibney, his wife Hanna, and their many children had “not only a national but a transatlantic reputation.” The family had been touring since 1875, rode the rails in their own custom-built Pullman Palace Car, and had played the White House just the year before, entertaining Rutherford B. Hayes.

The audience in Skaneateles surely got its money’s worth (25 cents for adults, 15 cents for children). An inspired reviewer for a newspaper in Friendship, N.Y., noted:

“This worthy and talented couple have surrounded themselves with olive branches from which leaves of music bud forth it would seem spontaneously. It is truly a most interesting family circle or to use another simile we might compare it to a flight of steps up to the temple of St. Cecilia.* The appearance of the nine McGibenys on the stage is so pleasing and homelike that it is impossible not to feel attracted towards them as one is not usually attracted towards ordinary musical or dramatic troupes… There is a novelty and a freshness about all they say, sing, play or do that is most pleasing and entertaining.” 1

Another author, in a book otherwise devoted to a condemnation of birth control, praised the McGibney family for its musicianship and fecundity:

“Before me, as I write these words, lies the picture of a model and gifted American family, to listen to whose music more than a million people have paid admittance to their entertainments, who are known throughout America, and who enjoy the friendship of some of the most distinguished Americans in the ranks of literature and art. Including the father and mother they number fourteen. Without one exception, they possess positive merit. For years they have traveled all over America, delighting audiences everywhere with their remarkable talents as musical artists.” 2

Their program itself, as described on their promo cards, included “a full band, a full orchestra and chorus… Gems of Music, in Cornet Solos and Duets, Band and Orchestral Selections, Vocal Solos, Glees, Choruses and Laughable Sketches that cannot be described, but must be seen to be appreciated.”

And so another famous family passed through Skaneateles.

* * *

Promotional cards by Courier Lithograph Co., Buffalo, N.Y., 1883, 1884

1 “Benefactors of Art,” Friendship Chronicle, July 7, 1880

2 The Crowning Sin of the Age: The Perversion of Marriage (1892) by Brevard D. Sinclair

* The temple steps to which the first writer draws an unexpected comparison are at Acatitlan, an Aztec site in the town of Santa Cecilia, northwest of Mexico City, and are shown below:

The Jenney Family

“I live on this lake and I say that God may be able to make something more beautiful than Skaneateles Lake, and purer water, but I don’t believe he ever did so.”

— Col. Edwin Sherman Jenney

The Jenney cottage in Spafford, near Ten Mile Point, was the summer place of one of the most remarkable families to ever grace the shores of Skaneateles Lake. The patriarch was Edwin Sherman Jenney of Syracuse, who raised and led regiments for the Union army during the Civil War, then returned to become one of the city’s leading lawyers, the husband of a remarkable woman and father of four, three of whom were successful lawyers and one of whom shaped American social history.

* * *

Of Edwin Sherman Jenney’s military history, two highlights interest me. The first is the odd way in which his military service came to a close.

In 1864, Major Jenney was serving in North Carolina when a new regiment, the 185th New York, was raised at home; the Major was promoted to Colonel and ordered to return and take command. On the homeward journey from North Carolina to Virginia, aboard a small steamer on the Dismal Swamp Canal, his party was ambushed by Confederate soldiers who closed a drawbridge across their path, shot down 10 of the 14 men on the boat, and marched the survivors 40 miles to a place where Maj. Jenney was given a parole (i.e., He gave his word not to take up arms against his captors until exchanged for an enemy captive of equal rank).

But Maj. Jenney had no faith that the parole, a slip of paper, would be honored by the next roving band of Confederate troops he encountered. Rather than march to the appointed place for exchange, he availed himself of the first opportunity to cut and run, stole a boat and rowed down the Elizabeth River and across Albemarle Sound to Union-held Roanoke Island.

A general there assured Jenney that he would be “exchanged” immediately, so he could safely re-enter the service with his new regiment. Relying on the promise, Jenney took command of the 185th New York and returned to war. Back at the front, he learned from newspapers sent through the picket lines that a reward was being offered for his capture as a paroled captive, and if taken, he would be executed.

Col. Jenney was discomforted. Seeing that he hadn’t been “exchanged” as promised, he urgently requested the War Department to formally declare his status as “escaped” rather than “paroled.” While he waited for a reply, he carried poison in his pocket to avoid being hung should he be captured again. In Washington, no agreement could be reached (imagine that) on his status. Singularly unhelpful was Secretary of War Edwin Stanton who refused to clarify Col. Jenney’s status and instead wrote that he took Jenney’s request to be a letter of resignation. Left twisting in the wind, Jenney opted for self-preservation, resigned in February of 1865 and returned to Syracuse to take up the practice of law.

The second fascinating incident in Edwin Jenney’s military career occurred earlier in the war, in 1863, when young Capt. Jenney married Marie Regula Saul, an 18-year-old Syracuse girl, and took his bride along to the war with the Army of North Carolina. Their honeymoon was shortened by incoming artillery fire, from which Mrs. Jenney withdrew in a dignified manner; in later years this would be cited as an example of her unflappable nature.

After the war, while Col. Jenney became a force in the legal community, Marie Saul Jenney became the dean of Syracuse clubwomen and the social and intellectual mentor of generations of women.

In 1922, her obituary noted, “Few New York state women of her station have exercised influence equal to that of Mrs. Jenney, or wielded power so long… She was the gentle dowager, the democratic aristocrat… Strong convictions, clear intellect and a large store of gentleness never mistaken long for weakness, made her a personage.”

At the age of 69, she marched in the first suffrage parade at New York City. Not surprisingly, she raised two daughters with courage and character to spare.

* * *

Born in 1867, Julie Regula Jenney attended schools in Syracuse and Chicago before graduating from the University of Michigan School of Law in 1892, the only woman in her class. She did postgraduate work in New York law at Cornell University, and in 1894 was the first woman admitted to the bar in Central New York; she practiced with her father’s firm, and built a large clientele among business and professional women who felt more comfortable with a woman lawyer. She organized the Legal Relief Society, the Syracuse Federation of Women’s Clubs, and the Professional Women’s League. She was active in women’s suffrage, saying that until women could elect the lawmakers they could not be sure of any rights whatever.

In 1920, she was named as the first woman Deputy Attorney General of New York State. In 1924, she asked a visiting judge how he dealt with cases of non-support, i.e., the deadbeat dads of the day. The judge believed in a lenient approach.

“I disagree,” said Miss Jenney.

“But what are you going to do,” said the judge, “when the husband says ‘She’s disgraced me by bringing me down here and I’ll stay in jail forever before I pay her a cent.’”

“Let him,” she said. “ I would have such a man’s bluff called every time.”

In 1908, William Beauchamp wrote of Julie, “She possesses not only strong intellectuality but a brave and courageous spirit and is battling earnestly and effectively for the advancement of women and for a just recognition of woman’s powers in the world.”

* * *

Born in 1868, William Sherman Jenney turned out along more traditional lines. He attended Princeton (Class of 1889), studied law at Cornell and followed his father and sister into the legal profession with the family firm in Syracuse. He eventually became the general counsel for the Delaware, Lackawanna Western Railroad Company, and moved to Manhattan; he summered at his home, “Little Close,” on Egypt Lane in East Hampton, a chip shot away from the Maidstone Country Club and the ocean.

* * *

And then there was Marie Jenney.

Born in 1870, she broke the mold of male conceptions every step of the way. Feeling called to the pastorate, she attended the Unitarian Theological Seminary in Meadville, Pennsylvania. Her eventual husband later wrote, “There were other women studying at the school, but Miss Jenney was different. She was too beautiful to be a minister. People insisted that she could not be serious. They argued that there was probably a man at the seminary who had brought her there. Only a man could explain such a beautiful girl, with good clothes and evidences of wealth, at a theological seminary. Women did not go in for careers thirty years ago, and saving souls was a man’s job.”

These were the words of Frederic Clemson Howe, who was smitten from his first glimpse of Marie Jenney in Meadville, although “stricken” might be a better word. Which made the clash of their beliefs all the more painful. He wrote:

“In so far as I thought of it at all, women were conveniences of men. Mothers were, sisters were, wives would be… Miss Jenney was different from this picture. And I did not like to have my picture disturbed, especially as I was so greatly attracted to the disturber.

“I expected women to agree; she had ideas of her own; they were better than my own, more logical, more consistent too with my democratic ideas on other things. She believed women should vote for the same reasons that men voted. I snorted at the idea. Women should go to college as did men and find their work in the world. This shattered my picture of her convenience in the home. Women, to her, should be economically independent, they should not be compelled to ask for money… they did their share of the common work, and marriage was a partnership. This destroyed my sense of masculine power, of noblesse oblige, of generosity.

“To her, life was not a man’s thing, it was as human thing. It was to be enjoyed by women as it was by men; there should be equality in all things, not in the ballot along but in the mind, in work, in a career. Men and women were different in some ways, they were alike in more.”

Marie Jenney graduated in 1897, was ordained at May Memorial in Syracuse, and became an assistant to another Unitarian minister, Mary Augusta Safford, in Sioux City, Iowa, and then led her own church in Des Moines. But she grew frustrated with her church’s lack of enthusiasm for social causes, the drudgery of her work and her treatment as a woman in a male profession. And her suitor kept writing letters.

In 1904, Marie gave up the ministry to marry Frederic Howe. The couple lived in Cleveland, Ohio, where both were deeply involved in progressive politics, and then in 1910 moved to New York City. Frederic became the Commissioner of Immigration. Marie was active in the New York suffrage movement and the National Consumer’s League, a group of women seeking to improve conditions for working women. She chaired the 25th Assembly District Division of the New York City Woman Suffrage Party, soon to be known as “the fighting twenty-fifth” under her leadership.

In 1912, in Greenwich Village, she founded a women’s club, Heterodoxy, for “women who did things and did them openly.” It was a gathering place for suffragettes, feminists, radicals, labor organizers and professional women who met twice a month to debate topics such as women’s rights, pacifism, birth control, revolutionary politics, and civil rights. The group included free-love advocates, lesbian couples, and heterosexuals both oft-married and monogamous.

Marie Jenney Howe was known to the women of Heterodoxy as the “mother;” she was present for them emotionally, intellectually, politically. One member noted that the women were “at home with ideas. All could talk; all could argue; all could listen.”

Also in 1912, Marie wrote “An Anti-Suffrage Monologue,” a satiric monologue that is still being performed today, in which an anti-suffrage woman points to female delicacy while warning that women would exert too much power, and point by point demolishes her own arguments. Some of the more oft quoted passages include:

“If the women were enfranchised they would vote exactly as their husbands do and only double the existing vote. Do you like that argument? If not, take this one. If the women were enfranchised they would vote against their own husbands, thus creating dissension, family quarrels, and divorce.”

“The great trouble with the suffragists is this: They interfere too much… Let me take a practical example. There is in the City of New York a Nurses‘ Settlement, where sixty trained nurses go forth to care for sick babies and give them pure milk. Last summer only two or three babies died in this slum district around the Nurses’ Settlement, whereas formerly hundreds of babies have died there every summer. Now what are these women doing? Interfering, interfering with the death rate! And what is their motive in so doing? They seek notoriety. They want to be noticed. They are trying to show off.”

“We antis do not believe that any conditions should be altered. We want everything to remain just as it is. All is for the best. Whatever is, is right. If misery is in the world, God has put it there; let it remain. If this misery presses harder on some women than others, it is because they need discipline.”

“What ought these women to do with their lives? Each one ought to be devoting herself to the comfort of some man. You may say, they are not married. But I answer, let them try a little harder and they might find some kind of a man to devote themselves to. What does the Bible say on this subject? It says, ‘Seek and ye shall find.’ Besides, when I look around me at the men, I feel that God never meant us women to be too particular.”

Even crusaders need to take a break, and Marie Jenney Howe sought summer refuge at a cottage in Siasconset, on the eastern end of Nantucket Island, where she would swim, sail, cycle, play golf and tennis. And each year she would take two stray dogs from a New York animal shelter and keep them at her cottage until she found homes for them on the island. In September of 1914, a newspaper article noted that she had included a kitten in that summer’s rescue, found across the street from a Suffrage association office.

“I call her the Suffragette, as she was yelling her heart out in an empty areaway with quite a crowd looking on. It was such a deep hole no one could get in to her, and I had to borrow a ladder from workmen to get her out. By this time the crowd stretched across the street. I supposed the kitten was making a suffrage speech; anyhow, she was proclaiming her wrongs.”

In 1917, two events cast a shadow over those who were calling for change in the United States. The U.S. entered World War I and a revolution in Russia overthrew the Tsarist monarchy and established a communist government. Suddenly America was at war with both Germany and Communism. The Espionage Act of 1917 forbade, among other things, any activity that interfered with military recruitment. The Sedition Act of 1918 prohibited “any disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language about the form of government of the United States.” The penalties included death, deportation and/or lengthy prison sentences.

The Bureau of Investigation, staffed with former Secret Service agents, began investigating draft resisters, pacifists, and immigrants suspected of radicalism, amassing files on 450,000 suspected radicals, of whom 10,000 suspected communists were arrested. Of this first Red Scare, Frederic Howe later wrote in his autobiography:

“Few people know of the state of terror that prevailed during those years…The prosecution was directed against liberals, radicals, persons who had been identified with municipal-ownership fights, labor movements, with forums, with liberal papers that were under the ban… I hated the Department of Justice, the ignorant secret-servicemen who had been entrusted with man-hunting powers… I hated the suggestion of disloyalty of myself and my friends.”

Dr. Sara Josephine Baker, Heterodoxy member and director of the New York City Bureau of Child Hygiene wrote in her autobiography, Fighting for Life (1939):

“I had the privilege, shared with a great many other women, of being suspected of mildly radical sympathies which during the war were, of course, synonymous with giving aid and comfort to the enemy. I was no pacifist whatever… but I did belong to a luncheon club for women active in various social and economic movements, and that was apparently enough. Perhaps it was the name [Heterodoxy] that alarmed the spy-chasers… The fantastic result was that we really did have to shift our meeting-place every week to keep from being watched.”

According to a letter from Sen. Robert La Follette to his wife (January 12, 1919), Marie Jenney Howe was seized in front of her apartment in New York City by the “Secret Service hounds,” taken into custody and not allowed to communicate with her husband or an attorney while they questioned her about her radical associates and activities – women’s suffrage and aid to the less fortunate being linked directly to socialism and pacifism, and thus tantamount to treason.

It must have been a nightmarish time for Frederic and Marie Jenney Howe, and while they were doing great good in the world, they were not there for one another. Mabel Dodge Luhan wrote of Marie Jenney Howe:

“She was married to a man who was deeply engrossed in humanitarian problems, who while he was Commissioner of Immigration, made Ellis Island bearable for thousands where before his time it had been purgatorial. He really tried to make it a hospitable and temporary home, while in her own home he was one of those husbands who seems perpetually engrossed in thought and never on the spot. When he wrote his autobiography and his wife read it, she exclaimed, ‘Why Fred, were you never married?’ He had neglected to mention this small fact.”

Fred hurried to write Marie into the book before it was published, but a point had been made. Taking another view of it, a mutual friend, Hutchins Hapgood, wrote, “I do not believe that she recognized Howe’s love for her, because of her suffrage and feministic poison, which had gone so deep in her whole personality.”

At some point, the Howes built a home, “Shadow Edge,” in Harmon-on-Hudson (now completely absorbed by the municipality of Croton-on-Hudson), a quiet spot that was still just an hour away from New York City by train.

In 1926, surprising everyone, Marie pulled up stakes for a time and moved to Paris to do research for a book on author George Sand. She visited Sand’s granddaughter at the ancestral home, and was given access to Sand’s letters and papers. In a letter from Paris to a friend she wrote, “If I continue to feel homesick I shall go back.” But she profited by her solitude; her book, George Sand: The Search for Love, was published in 1927. She then translated Sand’s journals into English and published The Intimate Journal of George Sand in 1929.

Back at home, she still missed Fred when he was gone, which was often. In 1927, when Fred traveled to Russia, she wrote to a friend, “I hated to have him go, and was sick for three days after he left. I went to bed, could not sleep, wept, stared at the ceiling and asked of the hard plaster, ‘Will no one ever stay with me?’”

Consolation came in the person of Rose Emmet Young, a member of Heterodoxy and an author herself, who became Marie’s closest friend, companion, and, some say, lover. Miss Young had written two novels, Sally of Missouri (1903) and Henderson (1904), and once noted, “Living is learning, and all learning finds its place somewhere in the making of stories.”

Marie had dedicated George Sand to Rose, and together they wrote, “Impossible George,” a three-act play based on the novelist’s life.

* * *

Born in 1873, Alexander Davis Jenney was the youngest of the four children, and something of a prince among men. He attended Princeton (Class of 1894) where he was the tennis champion, then Cornell Law School, graduating in 1896. He returned home, joined the family firm, married Miss Caroline King (who had studied in Paris). On their wedding tour, they “spent considerable time” at the Italian villa of Major Alexander Davis, for whom Alexander was named. (Maj. Davis once owned Thornden Park in Syracuse and had a large mansion there.) Alexander and Caroline had three children. A good lawyer, family man, the best tennis player in Syracuse, and a much-loved clubman, Alexander seemed to have it all.

* * *

And now that we have a cast of characters, on to the cottage on Skaneateles Lake:

In 1886, Marie Saul Jenney, the Colonel’s wife, purchased a portion of Lot 83 in Spafford, near Ten Mile Point, for $100 from George Barrow of Skaneateles and I assume this is the spot where the Jenneys built their first cottage.

In 1889, testifying before a hearing on a water bill in Albany, Col. Jenney said, “I live on this lake and I say that God may be able to make something more beautiful than Skaneateles Lake and purer water, but I don’t believe he ever did so. The people of Skaneateles village use the water and I wish the Syracuse people could have all they want of it.”

In 1897, the newspaper noted that Julie Jenney was spending time at the cottage.

In 1900, Col. Edwin S. Jenney died in Syracuse; he was just 60 years old.

In 1901, it was reported that William Jenney and family were at the cottage. Perhaps it was getting crowded; the newspaper notes that a portion of the land was deeded to Alexander so he could build his own place.

In 1903, Marie Saul Jenney spent the entire summer at the cottage.

In May of 1904, the Jenney cottage was completely destroyed by lightning, a $4,500 loss.

In 1906, the new cottage got indoor plumbing, thanks to J.S. DeWitt. And Alexander’s family was noted as visiting.

Mr. & Mrs. Alexander Jenney and children again visited in 1907, then went on to spend some time in Cazenovia. In August, Mayor Tom Johnson of Cleveland, Ohio, visited. He was a friend of Frederic and Marie Jenney Howe, who were at the cottage visiting Marie’s mother. Mayor Johnson came by automobile, which was a real novelty at the time.

In 1908, Marie Saul Jenney and daughter Marie Jenney Howe were at the cottage. Mrs. Jenney hosted a luncheon and skat was played.

(“Skat?” you might say. Indeed, Marie Saul Jenney was the daughter of George F. Saul, editor of the German-language newspaper, The Syracuse Union, and skat is the German national card game. It combines elements of bridge, euchre and pinochle, and the fact that Mrs. Jenney could hold card parties playing anything other than bridge speaks volumes about her social clout.)

After visiting her mother, Marie Jenney Howe went on to East Hampton, L.I., to be guest of Mrs. William S. (Nina) Jenney, her sister-in-law.

In 1909, Mrs. Jenney had friends in for luncheon and more skat; the group included her daughter Julie. The newspaper referred to the cottage as “Avene on Skaneateles.”( Avène is in southern France, home of a 250-year-old spa with thermal springs and lots of sunshine, and I assume that’s the allusion.)

In 1910, Alexander Jenney’s bungalow was completed.

In 1911, Julie Jenney was at the cottage.

In 1912, Mrs. Jenney summered at the cottage and Mrs. Alexander (Caroline) Jenney and children were in the Jenney bungalow. But cottage life was not without its hazards:

“Mrs. Alexander Jenney, who is spending the summer at her cottage at Skaneateles lake, was severely injured in a runaway accident yesterday afternoon [July 9]. Mrs. Jenney was unconscious for several hours and it was found that three ribs had been broken, but she was reported to-day to be resting comfortably.

“The Jenney cottage is situated about half way between the lake shore and the top of the high hills which border it at that point. The descent is very steep, the road leading to the cottage at one point running beside a deep ravine. Mrs. Jenney had been motoring with her little son, Alexander D. Jenney, Jr., and leaving the motor at the farmhouse at the top of the hill they got into a farm wagon to make the descent to the cottage. Soon after starting down the steep incline a part of the harness broke, and the horses plunged forward, throwing Mrs. Jenney and her son out of the wagon with great force. The child was unhurt, but Mrs. Jenney was unconscious for three hours as a result of the injuries she received.

“Dr. S. P. Stewart was sent for and later a trained nurse went from this city to care for her. Besides the three broken ribs Mrs. Jenney had a number of minor bruises.”

In 1913, Mrs. Jenney spent the summer with her son William on Long Island, and the Skaneateles cottage was occupied by Mr. & Mrs. A.H. Durston.

In December of 1914, Alexander Jenney, 42, died of heart failure, following a severe bout of influenza the previous year from which he never fully recovered. He had been staying at the Syracuse home of his mother; his wife was at his side when he died. The newspaper noted, “The end came rather suddenly, although not wholly unexpected. Mr. Jenney himself, it is said, had not realized that he could not recover.” Alexander left everything to his wife, in a will totaling 29 words. His three children were John King Jenney (10), Alexander Harding Jenney (8) and Cornelia Jenney (6).

There followed a succession of renters: In 1915, Mrs. Howard K. Brown and children occupied the Jenney cottage. In 1916, Mr. & Mrs. Edward L. Robertson and family were in the Jenney bungalow and Mr. & Mrs. Howard K. Brown took the Jenney cottage. In 1917, ’18 and ’19, the Jenney bungalow was taken by Mr. & Mrs. Charles Francis Teller and children.

In 1922, Marie Saul Jenney died at “Little Close,” the home of her son, William S. Jenney, at East Hampton. It had been hoped that the sea air would improve her health, “but its swift failure could not be checked.” Marie Jenney Howe later wrote of her mother’s death to a friend, “I had just lost my mother, and the house at Easthampton was so full of her that I couldn’t stand it and rushed back to Harmon. I still feel that I can never bear to… see that house where she died.”

In 1924, Caroline Jenney opened the camp; Mrs. and Mrs. James G. Grant occupied the cottage. In 1928, the Teller family again took the Jenney cottage; that was the last mention of it in the newspapers.

* * *

Caroline Jenney had one more tragedy to endure. In October of 1929, Cornelia Jenney, 21, who had graduated from Smith College in June and begun graduate work at Syracuse University, was crushed to death by a New York Central coal train at a street-level crossing, while driving to class.

In 1933, Marie Jenney Howe was tired, ailing and aging. She wrote in a letter:

“Fred has been in Washington. I am glad I can stay at home. I would rather read about all those upheavals than take part in them. Read about the big events and be content with small things. That’s pleasant. The morning paper – murder, crime & war – then I go out and feed my squirrels and look at the swollen river pouring down from the dam. The trees are just the same, no matter what happens. There they have been before we were born, there they will be after we are dead.”

In 1934, Marie Jenney Howe died of heart disease at the age of 63, at home in Harmon-on-Hudson. Arrangements for the memorial service and the closing of the house were handled by Rose Young.

In 1940, Frederic Howe died at Martha’s Vineyard Hospital; he was 72.

In 1946, William S. Jenney died at his winter home in Palm Beach, Florida. He was 78.

In 1947, Julie R. Jenney died at 81; her remains were buried next to those of her parents at Oakwood Cemetery in Syracuse.

* * *

My thanks to the Glen Haven Historical Society for sending me on this quest last year, and especially to Elsie Gutchess for the gift of Radical Feminists of Heterodoxy (1986) by Judith Schwarz which has been invaluable in putting this piece together.

My thanks as well to Michèle LaRue, who, since 1995, has performed Marie Jenney’s “An Anti-Suffrage Monologue” more than 200 times, keeping Marie Jenney’s words and spirit alive.