“Mid-Lakes Navigation Company’s Cruise Boats getting underway from Clift Park, Skaneateles, NY.” Photography by ABC Video and Photography

“Mid-Lakes Navigation Company’s Cruise Boats getting underway from Clift Park, Skaneateles, NY.” Photography by ABC Video and Photography

My thanks to everyone who braved the coming (and freezing) rain to attend my Ben Porter talk at the Creamery. It was a delight to be with you all.

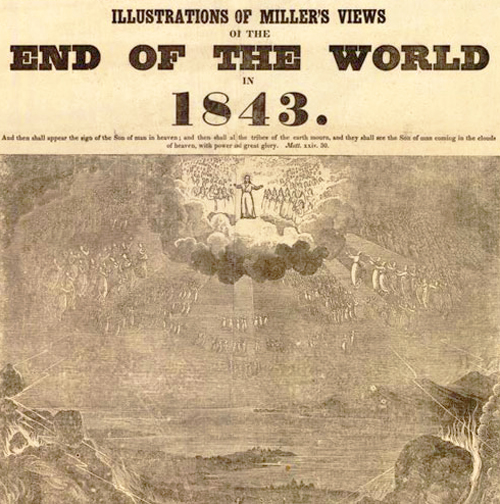

For years William Miller had been proclaiming the Second Coming of Christ would occur in 1843, with the rapture of the faithful and the destruction of those left behind. His believers, dubbed Millerites, numbered in the thousands. Another William, by the last name of Beauchamp, did not take it seriously. He was not impressionable, and very much a 12-year-old boy enjoying his boyhood in Skaneateles. But years later he would write about events that prompted him to momentarily reconsider the prophesy.

“One morning a man came down the street from the east, uttering an occasional loud cry. He stopped in front of [John] Snook’s store, and commenced a discourse. People soon made up their minds that he was drunk or crazy, and a pail of water was emptied over him; but as this made no difference, he was marched off to Judge Jewett, who charged him to create no disturbance. There was no special interference with him afterwards, except as the boys used to snowball him. He walked around at intervals of weeks and months, smoking and preaching, and when a well directed snowball from Clinton Brainerd took the pipe out of his fingers he took no notice of it. But he stopped just after, and pointing to the stores opposite, said, ‘Boys, if the world should come to an end, what a smashing of glass there would be.’ This was the ridiculous side.”

And then came the Great Comet of 1843, in February and March.

“One cold winter’s night it did not seem so ridiculous. We were sliding down hill. The tail of the comet, the head of which we never saw, was streaming halfway across the sky. The moon was shining, and the northern lights were up. They were much as usual at first, but soon began to float all over the sky in fantastic forms, and with changing colors. They drew up abreast of the moon, and deployed in line, and turned blood red. And in the midst of all, in the still evening hours, the voice of the preacher would burst out here and there in the streets, announcing a swift destruction to the earth and the inhabitants thereof. It was a scene to make a deep and thrilling impression.”

* * *

Quotes from Notes of Other Days in Skaneateles (1867) by the Rev. William T. Beauchamp

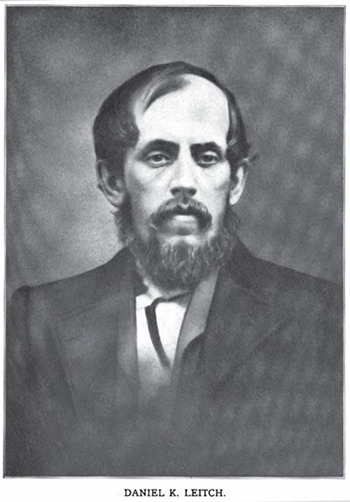

Daniel Kellogg Leitch was born in Skaneateles on September 28, 1834, the son of George Leitch and Catharine (Kellogg) Leitch, and the grandson of Daniel Kellogg, attorney and financier. He did not spend much of his childhood here, attending first Aaron Skinner’s boarding school for boys in New Haven, Connecticut, then Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, followed by Union College in Schenectady and Albany Law School, graduating in 1860. He practiced law in Auburn for a year, but then “was called home to assist his mother in financial affairs.”

Managing the Kellogg money was a full-time job for the descendants of Daniel Kellogg. He had died in 1836, and left a fortune estimated in the “several hundreds of thousands of dollars,” held in trust for his wife and seven children. To give you an idea of its value: $100,000 in 1836 would be the equivalent of $2 million today. And Daniel Kellogg left “several hundreds.” Also, the estate of Daniel Kellogg’s brother-in-law, David Hyde, in trust for Hyde’s daughter, Chloe, was interwoven with the Kellogg trust.

D. Kellogg Leitch’s father, George, was the original executor and had active charge of the estate. By 1848, he had borrowed heavily from the Kellogg estate, and the Kellogg estate had borrowed from the Hyde estate. George Leitch, to compensate Chloe Hyde, conveyed to her two properties in Syracuse that he valued at $47,000. However, the properties were actually worth much less and, surprise, mortgaged by George Leitch for at least half their value. In short, when George died in 1855, he had pretty much made a dog’s breakfast of the estate and its accounting. Hence, it is no surprise that Catherine Leitch called her son home in 1861 to assist in her financial affairs.

Catherine died in December of that year, but D. Kellogg Leitch did not return to the practice of law. He served as Justice of the Peace for one year, and then retired, spending his time almost wholly indoors, citing his “failing health.” At his home on East Academy Street, his wife Lavinia, who he married in 1867, saw to his needs, with the help of a servant and a handyman/gardener.

D. Kellogg Leitch spent his time in reading, and receiving the occasional visitor. He became known as an excellent source of free, trustworthy legal advice, for businessmen and poor men alike. Such was his knowledge of his library that when a question was raised, he could point to a book on the shelf, give the page number, and say, “You will find your answer there.”

He was also known to be generous to those in need, and especially for anyone who had lost an animal. When the First Presbyterian church was in need of funds, D. Kellogg Leitch could be relied upon to advance the necessary sum. He could also be counted on to host Sunday School picnics, of churches both Catholic and Protestant, on “his grounds.”

He was generous with the village as well. On July 27, 1871, the Skaneateles Press reported:

“We understand that D. Kellogg Leitch, Esq., has given a strip of land, twelve feet wide, running along the east side of John Street from Genesee to Elizabeth, upon condition that the corporation will grade the same to a level with the traveled street, and set out trees and make other necessary improvements. The addition will give the street a width of 51 feet and 6 inches. In consequence of Mr. Leitch’s liberality, the name of the street will be changed to Leitch Avenue.”

In 1883, D. Kellogg Leitch became the executor of the Kellogg trust and served in that capacity until his death, at the age of 51, in 1891. He was remembered as a scholar and a gentleman, by a street named in his honor, and his monument in Lake View Cemetery.

* * *

Frederick R. Spencer’s portrait of Daniel Kellogg, which hung in Kellogg Leitch’s home on Academy Street, was given to the Onondaga Historical Association by Leitch’s widow in 1908.

Charles Loring Elliott’s “very competent” copy of Spencer’s portrait (shown above) was done in 1837 for the Bank of Auburn, and is today in the collection of the Schweinfurth Memorial Art Center in Auburn.

Lavinia Leitch also made a donation in her husband’s memory toward the stained glass windows of the First Presbyterian church.

The photograph of Daniel Kellogg Leitch at the beginning of this piece is from Past and Present of Syracuse and Onondaga County, New York (1908) by The Rev. William M. Beauchamp.

For a glimpse into the thicket of the Kellogg finances, I would recommend “Kellogg v. Kellogg” in Reports of Cases Decided in the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court of the State of New York (1916) on Google Books.

The present residents of Leitch’s home on Academy Street found some of his books in a crawl space, behind a trap door, and thoughtfully passed them on to the Skaneateles Historical Society. Below, Leitch’s signature on the flyleaf of Things as They Are in America (1854) by W. Chambers:

One afternoon in April of 1948, Oscar J. “Bud” Chase was tending bar at the Lakeview House on Genesee Street, when a red coupe pulled up to the curb and its occupant stepped out into the sunshine. “Hey, know who that is out there?,” said Chase, looking out the window. “That’s Jack Smart, the radio’s Fat Man!”

Indeed, every Friday evening at 8 o’clock, thousands of listeners leaned closer to the radio as an announcer whispered, “There he goes, into that drugstore. He’s stepping on the scales. Weight? 237 pounds. Fortune? Danger. Whoooooo is it?” And then Jack Smart’s deep, sonorous tones answered, “The Fat Man.” Yes, right on Genesee Street in Skaneateles stood the radio drama’s Brad Runyon, the “stout but stalwart” detective.

And Bud Chase knew him on sight because they had met years before in Buffalo, Smart’s hometown. In fact, Smart was on his way from New York to Buffalo to see his mother. But first he was greeted by Chase and led into the Lakeview to meet the boys at the bar and proprietor Jacob “Jake” Brounstein.

Soon the center of attention, he drew pictures of himself on the backs of envelopes, autographing them “J. Scott Smart.” After a short visit, he was off to Buffalo, but not before impressing everyone in the Lakeview with his real-life girth, quick answers and down-to-earth personality.

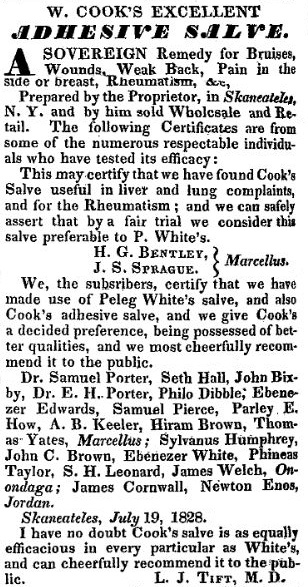

Warham Cook (1766-1834) was locally famous as the inventor of Cook’s Salve. From the 1828 advertisement above, you can see that many in the surrounding towns endorsed it. The recipe for a similar product was given below in The House We Live In: How to Keep It in Order, or, The Experience of Seventy Years’ Successful Practice of the Medical Profession, East and West, in Plain English for the People (1869) by Drs. Parker Sedgwick and S.P. Sedgwick:

A few notes for the modern reader:

“Venice turpentine” is a resin produced from western larch trees, and has the consistency of honey. It is still used today by artists, as an additive to oil paints, and by farriers as a hoof dressing.

A drachm/dram is an apothecary’s measure for 1/8 of an ounce.

Peleg White’s Salve – apparently the standard against which all other salves were measured – was made of resin, mutton tallow and bees-wax. One writer noted, “It is adhesive, contains no irritating ingredient, and is as cheap as could be desired.”

For further reading, Dr. Chase’s Recipes – several editions of which can be found on Google Books – contained recipes for salves that could be made at home, and generally applied as follows: “In cuts, bruises, abrasions, etc., spread the white salve upon a cloth and apply it as a sticking plaster until well.”

The Village of Skaneateles acquired the land for Clift Park in 1888, but argued about what to do with it until 1892. Those in favor of green space won, and the park was named for Joab Clift, the previous land-owner, who donated a fountain. Clift was a successful farmer and businessman, and a one-time president of the Skaneateles Savings Bank, and so a useful man to honor. The park would be the subject of post cards for years to come.

Today, should you want to pay your respects to Mr. Clift, you can find his fountain across the street, just to the west of The Sherwood Inn, and his gravestone in Lake View Cemetery.

In 1873, the Christian Weekly ran a short piece entitled “Skaneateles Lake,” illustrated with a woodblock engraving from a drawing by Paul Dixon.

“There are a multitude of spots in this country, out of the track of the ordinary tourist, which were they in Europe would long ago have been famed in poetry and song. They waste, as we may say, their sweetness on the desert air.* At least they do not attract the attention which their intricate merits deserve. Such a spot is Skaneateles Lake in Onondaga County, N.Y. This beautiful sheet of water is some sixteen miles long by two miles wide. It affords a fine opportunity for the fisherman to enjoy his favorite sport, and gives to the lover of the picturesque abundant gratification. For complete rest, apart from the bustle of busy city life, away from the chains of fashion, the tyrannical goddess, such spots as these are to be sought. Here body and mind and heart can be refreshed; here the restoring power of nature can be enjoyed to the full, and from here one can return to the burdensome duties of life with memories of beauties that will be a constant joy.”

*An allusion to a line in Thomas Gray’s “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard” (1751): “Full many a flower is born to blush unseen,/And waste its sweetness on the desert air.”

The picture is odd, in that it doesn’t appear to be a view of Skaneateles Lake. In May of 1872, Dixon had done the picture below for Appleton’s Journal; note the similarities, including the “Boats to Let” sign. One wonders if Dixon didn’t use an earlier sketch of a different lake for the Christian Weekly assignment.

“Granite, slate, and limestone hills, charming valleys, extensive plains of gently rolling surface, rugged elevations, and lofty mountains, alternate with streams, cascades, ponds, and beautiful lakes of all dimensions, from the calm and transparent amenity of Skeneateles, to the inland seas of Erie and Ontario.”

— From “New York” in The United States and the Other Divisions of the American Continent (1833) by Timothy Flint

“I need not inform you, that another branch of this [Erie] canal connects the Hudson with lake Champlain, and that by lateral cuts it is already connected with many interior lakes, rivers and important points of water communication, and that still more lateral canals of this sort are in progress, or in contemplation. I need not here mention the numerous villages in the central parts of this great state, of surpassing beauty of position and scenery. Among them Canandaigua and Skeneateles hold the first place. The naiads of this charming chain of interior lakes and fountains will soon be scared from their greenest and most secluded retreats by the sound of the bugle of the canal boats, and the hackneying trample of canal horses and boys.”

— From “A Tour” in The Western Monthly Review, October 1828