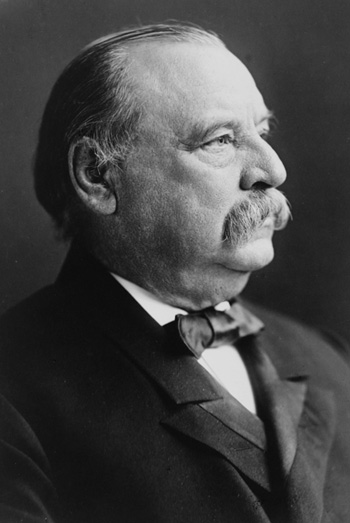

They said Howard Moffat reminded people of President Grover Cleveland, the portly man with a mustache and bow tie whose portrait above might give you an idea of Howard’s appearance. He was a kindly man as well. He went sailing on Skaneateles lake every morning and every afternoon, all summer long, and delighted in taking young children along for the ride, sometimes as many as 20 at a time.

The kindly sailor was born Thomas Howard Moffat on March 20, 1837, the fourteenth and last child of John Little Moffat and Hannah Curtis Moffat. You might think he had many playmates, but that was probably not the case. Most of his siblings had already died, in infancy, and the closest survivor was a brother 15 years older; that was George; he died when Howard was 10. Howard was left with a brother and two sisters who were 20 or more years his senior.

To heighten his estrangement, he’d been born in Nacoochie, Georgia, not in New York City where the first thirteen Moffats had come into the world. John and Hannah Moffat had gone south during the now largely forgotten Georgia Gold Rush, John making his way as an assayer of gold. The Moffats and their young son returned to New York, and in 1849, John Moffat went off to California for two years, drawn there by the Gold Rush we do remember, measuring miners’ gold and turning it into something they could use, like bars and freshly minted coins. (A single Moffat gold coin, depending upon its condition, today brings between $3,000 and $100,000.)

At some point in his youth, Thomas Howard Moffat, named for an uncle who was a sea captain, changed his name to Howard Fenwick Moffat. I don’t know why. There are no other Fenwicks in the Moffat or Curtis families. Perhaps he didn’t like his uncle.

In 1859, Howard’s mother died in Brooklyn. Soon after, Howard joined the U.S. Navy. His enlistment date was March 28, 1860. He was 23 years old. Howard’s first ship was the U.S.S. North Carolina and his second the U.S.S. Falmouth. The North Carolina was a “receiving ship” for recruits, largely used to see that the newly enlisted did not have second thoughts and slip away, and the Falmouth was a “store ship” that provisioned others. The Falmouth steamed off for Panama on April 1, 1860, which suggests that Howard’s time on the North Carolina was limited to two days.

Howard’s early tours, however, were rendered insignificant on April 12, 1861, when Fort Sumter was bombarded and the Civil War began in earnest. On July 31, 1861, Howard was appointed Acting Master’s Mate aboard the U.S.S. Richmond, a wooden steamer shown below. Master’s Mate was the rank of an experienced petty officer, one who served as a deputy to the lieutenant on each watch, saw that the ship was adequately provisioned, examined the ship daily and reported any needs or problems to the master.

The Richmond departed New York’s harbor on February 13, 1862, and steamed south to join the Blockading Squadron, arriving at Ship Island, off the coast of Mississippi, on March 5th. Then, led by Flag Officer David Farragut, the fleet prepared to seize New Orleans, moving to a position below the Confederate Forts Jackson and St. Philip. With more than 100 guns, these forts were the city’s main line of defense.

On April 24, at 3 a.m., the fleet of 15 vessels formed into two columns and Farragut signaled to commence the run past the forts. This is the place where the unwary writer might stumble and use a cliche such as “and then all Hell broke loose.” But it really was a Hellish scene. It was the middle of the night. Black smoke belched from the stacks of the Union steamers and was soon joined by the billowing smoke of the cannons. In the Stygian darkness the only light came from flashes of cannon fire, until rafts filled with blazing pine knots floated into the melee from upstream, sent down by the Confederates to break up the Union attack. The flames towered as high as the ships’ masts.

The leading ships came under attack by Confederate ships while those farther back in the column were still under fire from the forts. The Richmond was hit by cannon fire 17 times above the waterline, but her chain armor stopped many rounds; only two men were killed and three wounded. Howard Moffat was unscathed, and had the month of May to ponder his good fortune.

In June, Farragut took the fleet upriver toward Vicksburg, a city guarded by a bristling array of cannons placed on bluffs high above the river, cannons which had a wide open field of fire. To make the challenge more interesting for the Union fleet, the Mississippi had chosen this spot to loop back on itself, forcing passing ships to negotiate tight curves on the river while dodging shot and shell from above.

Farragut’s goal was to run this gauntlet of guns, take his fleet north of Vicksburg, and link up with Union ironclad river boats coming down from the north, securing the length of the Mississippi for the Union. At 2 a.m. on June 28, 1862, Farragut ordered the hanging of two red lanterns on the mast of his flagship, the U.S.S. Hartford, signaling the fleet to proceed. At 4 a.m., the approaching Union ships came within range of Vicksburg’s 29 heavy guns.

For two hours, the guns of Vicksburg fired down upon Farragut’s fleet. None of the ships were destroyed, but the Union lost 15 men killed and 30 wounded. Aboard the Hartford, Farragut’s cabin was blown apart by a shell just seconds after he moved to another part of the ship. On the Richmond, Howard Moffat sustained a wound to his left forearm, probably one that shattered the bone, making a quick amputation necessary.

I don’t know where Howard recovered from his wound, or where he was assigned afterwards, but he remained in the U.S. Navy throughout the war. In 1873, he formally retired and was granted a pension. The Federal Register noted:

CHAP. CCLXXX. An Act for the Relief of Howard F. Moffat. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, that the President of the United States be, and he is hereby, authorized to nominate, and by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, to appoint, upon the retired list of the navy, with the rank of master, Howard F. Moffat, now a volunteer officer on the active list of the navy. Approved, March 3, 1873.

By 1875, Howard Moffat had made his way to Skaneateles. He was, in fact, a first cousin of George Leitch (whose mother was a Moffat), but Leitch had died in 1855, long before Howard moved to the village. Perhaps Howard visited here when he was a boy. The stated reason for his coming, however, was that he had heard Skaneateles was good for sailing.

Very good for sailing, no doubt, during the daylight, with no cannons firing upon you, no fire rafts, no cries or screams rising from the smoke and flames.

Howard’s first boat was the May, named for May Wheaton, the daughter of a friend. It was a small boat, and he soon replaced it with a larger one, the Eva. Sedgwick Smith describes the Eva as follows:

“Eva was an old straight bow sloop, painted black. She was 31 feet long and very wide with a roomy cockpit surrounded by a mahogany coaming. She was steered with a tiller attached to an outboard rudder.”

Howard Moffat handled the boat by himself. He would hold the tiller by his side with the stump of his left arm, and steer by pushing the tiller with his body. He handled the ropes and sails with his right hand, cleating the jib sheet in light winds. It was said he could coil a rope faster with one hand than most men could with two. The Eva carried a good amount of railroad iron for ballast, and was hence very stable.

It was a time when most ladies could not swim, but many trusted themselves and their children to “Captain Moffat.” He loved children, and would take as many as 20 sailing at a time. He also made a point of taking school teachers out sailing, and while on the lake he would ask about the needs of their pupils, and later buy the necessary school books for those who could not afford them.

He put his boat in early in the spring and took it out late in the fall, and went sailing every morning and afternoon when the weather allowed. And the one-armed sailor never had an accident.

The Eva was wrecked against the wall of Thayer Park during heavy weather in October of 1886. Moffat replaced her with another large boat named Sunshine. In 1890, it was observed that he made more than 100 trips each summer, taking an average of 12 or more passengers on each trip.

“Captain” Howard Fenwick Moffat died on April 26, 1892, at Amber, New York. He was 55 years old, and was, without doubt, keenly missed in the summers that followed.

* * *

For the story of Moffat’s time in Skaneateles, I am indebted to Sailing on Skaneateles Lake (1934) by Sedgwick Smith. The paintings above are Farragut Passing the Forts at the Battle of New Orleans by Maurits Frederik Hendrik de Haas and Capture of New Orleans by Union Flag Officer David G. Farragut by Julian Oliver Davidson.