A carriage horse tethered to a hitching post outside the dry goods store of John and Annie Duckett.

A carriage horse tethered to a hitching post outside the dry goods store of John and Annie Duckett.

Marie Dressler was a star of the stage, and would soon become a star of the screen as well. In 1910, she was filling the Herald Square Theatre on Broadway for every performance of “Tillie’s Nightmare,” portraying a drudge in a boarding house. The playwright, Edgar McPhail Smith, set the first act in an upstate village called Skaneateles. Dressler thought the setting was fictional, but upon learning otherwise said she must visit.

In January of 1911, when Tillie’s touring company played the Wieting Opera House in Syracuse, Dressler saw her opportunity. She arrived in the village by trolley and was met by the wife of Samuel Montgomery Roosevelt, along with Mrs. W.J. Shotwell and Miss Mabel Avery. After a brief walking tour for the benefit of Ms. Dressler and a photographer, the star was whisked off to Roosevelt Hall in Mrs. Roosevelt’s sleigh. It was left to her manager, John H. Dalton, to chat up the locals at the bar of the Packwood House.

While Dressler professed to be delighted and charmed by the village, the local press was less so. Before the visit, a reporter for the Auburn Advertiser noted, “Marie Dressler has a play, the plot of which is said to be laid in Skaneateles. As some of the situations are somewhat risqué, we conclude that the writer does not know Skaneateles very well. Skaneateles does not get any gayer to speak of than standing around the steamer to see excursionists come and go.”

Two days after the visit, a reporter for the Syracuse Herald complained of being snubbed. “It was a Marie Dressler’s greeting in all her greatness – not 200 pounds of infectious laughter spread over six feet, but so much of crushing loftiness.” He was not invited to lunch at Roosevelt Hall and instead had to settle for drinking beer at the Packwood House. (Perhaps because the Herald‘s review was headlined, “A Real Nightmare.”)

Upon her return to the Packwood, Dressler said, “Talk about Versailles and all your European piles, Roosevelt Hall with its exquisite furnishings beats them all.”

And then it was back onto the trolley and off to Auburn for the evening’s performance.

* * *

A highlight of “Tillie’s Nightmare” was Dressler singing “Heaven Will Protect the Working Girl,” in which a young girl’s mother says, “The city is a wicked place as anyone can see… So every week you’d better send your wages back to me.”

* * *

“Tillie’s Nightmare,” The Post-Standard, January 3, 1911

“A Real Nightmare,” Syracuse Herald, January 3, 1911

“’Tillie Blobbs,’ Alias Marie Dressler, Has Time of Her Life in Skaneateles; Is Entertained by High ‘Sassiety’ and ‘Pop’ Conron, the Village’s ‘Mayor’,” Syracuse Herald, January 5, 1911

“In Tillie’s Town,” The Auburn Citizen, January 5, 1911

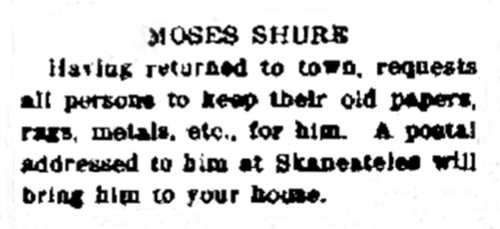

Yes, Skaneateles had a junk peddler. If you had scrap metal, newspapers, rags, any kind of junk at all, he would come to you and cart it away.

Moses “Movsha” Shure was born in Lithuania in 1873, when the country was a part of Tsarist Russia. He was conscripted into the army in 1896, one of more than 15,000 Jews to enter the Russian army that year. Life in the army was not easy for a Jew. As the Jewish Encyclopedia of 1903 observed:

“…service in the Russian Army entails more hardships upon the Jews than upon non-Jews, for the following reasons: (a) In military service the Jews are often prevented from observing the laws of their religion, as, for instance, concerning kosher food; (b) the relation between Jewish and Christian soldiers is not very pleasant, and the treatment of Jews in the Army is most unsatisfactory; (c) the military service does not give any privileges to the Jewish soldier, who is compelled to leave the place of service for the pale of Jewish settlement immediately upon the completion of his term of service.”

In 1906, Moses Shure and his wife Anna made their way beyond the pale to America, where Marcus engaged in the humble trade of junk peddler, a time-honored forerunner of recycling. His native language was Hebrew; he spoke Russian as well; English must have been a challenge at first.

Shure had family and a Jewish community in Syracuse, but early on he gave Skaneateles a try, renting a house on West Elizabeth Street. I am guessing that, at the time, the entire Jewish community of the village consisted of the Shure and Brounstein families. Marcus Brounstein, also an émigré from Russia, had a clothing store here for more than 50 years.

In the winter of 1911, Shure put his horse up for sale, a 9-year-old mare, “kind and true.” She could be seen at Marcus Brounstein’s barn on Jordan Street. I believe this is when Shure’s time in the village came to an end.

Moses Shure spent the rest of his life in Syracuse, where he had a junkyard. He never became an American citizen, remaining a Russian national, noting on one form, “got 1st paper, rejected by Court on 2nd.” He died in 1945 and his mortal remains were buried in the Chevra Shas section of the Jamesville Gate Cemetery.

* * *

Note: The “Pale of Settlement” was a region of Imperial Russia where residency by Jews was allowed and beyond which Jewish residency was mostly forbidden. The English term “pale” is derived from the Latin word palus, a stake, extended to mean an area enclosed by a fence or boundary. The Russian Pale of Settlement included all of Belarus, Lithuania and Moldova, much of Ukraine, parts of eastern Latvia, eastern Poland, and some parts of western Russia.

The house last known as “the Thorne house” was home to just two families over its 100+ years. First came Dr. Benedict.

A graduate of the Yale Medical School, class of 1836, Dr. Michael Dunning Benedict moved to Skaneateles from Connecticut in 1838, with his wife, Angelina, and his daughter, Adele. In November, he set up a medical practice offering his services in medicine, surgery and midwifery. In 1846, he had a house built on Syracuse Street (now State Street), a few doors “north of the Baptist Church.”

One of Dr. Benedict’s first triumphs was the healing of James Welling, who had fallen off the top of J.C. Porter’s house. And Benedict did it without bleeding the patient, a treatment still recommended by older physicians.

More than a doctor, Dr. Benedict was a joiner and a leader. He served as president of the Skaneateles Horse Thief Society and as the “Noble Grand” (president) of the Odd Fellows Lodge, and was a member of the Sons of Temperance and the Farmers’ Club.

As a farmer, Benedict kept 20 acres north of the village and grew an award-winning variety of pears, including White Doyenne, Clout Morceau and Flemish Beauty, Fall Pippin apples, Isabella grapes, Early June peas, as well as Ash Leaf Kidney and Early Pink Eye potatoes, and White Spine cucumbers. He also made currant wine which, given his membership in the Sons of Temperance, he probably drank in moderation.

More importantly, he was active in the anti-slavery movement, attending meetings and speaking publicly. And doing even more in private.

In 1937, Elizabeth Holley, the daughter of Adele and the granddaughter of Michael and Angelina, shared this memory passed down to her by Adele:

“Escaping slaves were hidden in the barn… Her father [Michael] warned her with great seriousness never to repeat to anyone what she saw or heard, as it would cause much trouble to many people if she talked. Many a night she would hear a carriage or sleigh drive in, hear her father called in a low tone, hear him go out and then there was a terrifying silence. The slaves were brought… and, when safe, passed on… and so toward Canada. Sometimes they could be sent on in a few hours, but in at least one case a man was hidden at Dr. Benedict’s for a week. His feet were frozen and Dr. B. took care of him and my grandmother cooked his food secretly and it was carried to him at night.”

As for his patients, many of them seemed to prefer being treated for free, and his public pronouncements began to betray an increasing frustration with the business side of life in Skaneateles. In February of 1858, he ran an ad that read, “I must pay my debts—and I intend leaving Skaneateles in the ensuing season. Nota Bena! All persons indebted to me are urgently solicited to call and settle forthwith.” This was followed in March by another notice: “My [farm] land is sold—my residence is still in the market. Any person wishing a very comfortable and pleasant home will find this a rare opportunity to purchase one. Price $3,500. Those persons having unsettled accounts on my books will find it much easier arranging them with me than with the constable.”

In January of 1859, perhaps as a stop-gap, Dr. Benedict accepted the position of “Physician in Chief” at Glen Haven, and recommended that his patients now see Dr. W. Van Steenberg, a graduate of Vermont University, whom he described as well educated and competent. However, in September Dr. Benedict severed relations with Glen Haven, and two months later ran an ad that said, “FAIR WARNING. My notes and unsettled accounts, from this date will be in the hands of James Tyler for collection and settlement. I cannot do business any longer upon the system of everlasting credit.”

When the guns of the Confederacy opened fire on Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861, and the Civil War began in earnest, Dr. Benedict saw his duty and an end to his frustration. Although 47 years old, he was mustered in as a surgeon with the 75th N.Y. State Volunteers on October 25, 1861, with the rank of Major, and in 1862 he was made Brigade Surgeon on the staff of Gen. Godfrey Weitzel, traveling to New York City, then by boat to Florida, then on to Louisiana.

The 75th first saw action in Louisiana, including at the siege of Port Hudson on the Mississippi River. In November of 1862, Dr. Benedict wrote a letter to the Skaneateles Democrat and described some of what he lived and saw:

“I was riding with Gen. Weitzel near the head of the column when suddenly three or four shots were fired, and the General ordered me to ride back and bring up the infantry. This I immediately did; and then selected a house in the rear, which was closed. I broke open the doors and found the family had left about an hour before, except an old negro man and woman who had been left in charge while their rebel master had fled to the Swamp.

“I found six good beds with two mattresses each and an abundance of bed clothing, and of these I directly had twelve nice double beds made, and put on the floor. I found a yellow curtain which I hoisted on a stake for an hospital flag—sent an orderly forward to direct the Surgeons of the several regiments where to send their wounded men—had the negroes kill some chickens and make a large kettle of chicken broth, and then rode on to the battle field. There was a constant roar of artillery and crash of musketry and for a short time the action was very hot… In the mean time I had the ambulances actively engaged in bringing back the wounded, and in a short time the hospital was filled.

“A floating bridge… was opened across the stream… and I was obliged to open a large two-story brick house on the opposite side for additional hospital accommodations, and the way I galloped about for the remainder of the day was rather busy.

“After the fight… I had all the wounded, both our own and the enemy’s, as far as we could find them, conveyed to the brick house and there I remained until 11 o’clock at night assisting the regimental surgeons in surgical operations and dressing the wounds. At that time we had everyone as comfortable as possible under the circumstances, when I took my supper, lay down on my blanket and slept until 5 o’clock in the morning. At which time I was again up and in the saddle…

“We paid the same attention to their [Confederate] dead and wounded that we did to our own, which seemed mostly to surprise them. I received a report from Dr. Comings yesterday saying that the neighbors and planters had shown them the utmost kindness, bringing in eggs, butter, milk, bedding, and other things for the comfort of the poor fellows, and three or four ladies watching them every night. A company of cavalry went up yesterday and found the country cleared of everything like an armed man, and the people frightened almost out of their wits.”

And then there was Henry Kelso. One afternoon during an officers’ meeting in Gen. Weitzel’s tent, a young runaway slave presented himself and asked to be allowed to become a servant for a member of the General’s staff. The General waved his hand and said, “Well, there they are—take your pick.” The young man deliberated and then approached Dr. Benedict and said, “I would like to go with this gentleman.” And so he did, accompanying Dr. Benedict throughout the war and then on to Syracuse, where Dr. Benedict practiced medicine after the war and Henry Kelso was a lifelong friend of the family.

After three years of service, Dr. Benedict was mustered out, on December 6, 1864, at Auburn, N.Y. After a brief stint as Medical Inspector of the U.S. Sanitary Commission at Washington D.C., he resumed the practice of medicine in Syracuse, N.Y. And he did finally find a buyer for his house.

On May 11, 1865, the Skaneateles Democrat reported, “Julius Earll has taken possession of the house lately occupied by Dr. M.D. Benedict and is remodeling it.” Three months later, Earll bought “Beauchamp’s late residence” at the corner of Syracuse and Elizabeth Streets, putting together four lots.

Julius Earll, a successful business man and manufacturer, had the wherewithal. Beginning in 1855, with his father, Hezekiah, and brother, George, he ran a huge distillery on the outlet in Hart Lot (about midway between Skaneateles Falls and Elbridge). In addition to producing whiskey, the spent grains from distilling were used to fatten hogs and cattle, whose manure fertilized crops of tobacco, with profit all along the way.

But there was a cloud on the horizon: the advent of the Civil War. The conflict was costing the Union $2 million a week. And so Congress passed the Tax Act of 1862, placing a tax of 20 cents per gallon on all spirits made after the first day of July. Every distillery in the country, including the Earll distillery, ran day and night until the last hour of June 30th, building up a large stock of untaxed whiskey, which, the next day, rose to the value of taxed whiskey. This netted distillers and speculators thousands of dollars. But as the tax rose – first to 60 cents then $1.50 per gallon in 1864 – distillers began dealing more in taxes than in whiskey. That year, the Earll Brothers Distillery paid $27,488 in taxes (roughly equivalent to $450,000 in 2020).

On January 1, 1865, the tax jumped to $2 a gallon, matching the actual cost of distilling, and Julius and George began converting their distillery into a paper mill. This was completed in August of 1868, the business becoming the Hart Lot Paper Co. The Syracuse Daily Standard observed, “When finished it is to be one of the largest in the State, and we trust will contribute in the future to the welfare of mankind at large as heretofore has to their degradation.”

Julius Earll also served as the postmaster of Hart Lot, and when at leisure was the only man who tried to stop illegal fishing with nets on Skaneateles Lake. He had the resources and the enthusiasm, but was fired on and attacked, and saw two of his yachts scuttled, one while he was sleeping in it.

In 1876, Julius Earll died at home of Bright’s Disease. His widow, Sarah, and son, Julius H. Earll, remained in the home, and in 1877, daughter Julia married John E. Waller, who joined the household.

As a businessman, John Waller was very much like his father-in-law. He served as president of the Skaneateles Savings Bank, the Hart Lot Paper Company and the Skaneateles Railway Company.

Waller also served two terms as president of the village, in 1897 and 1898. Admitted to the bar in 1878, he had also practiced law before his business interests came to occupy all of his time.

In 1878, Winifred Waller was born at home, making three generations under one roof, with two servants as well.

But wealth could not assure happiness. In February of 1882, Julius H. Earll died after an ice-boating accident, impaled on the sharp iron runner of another boat. He was carried off the lake to his home, where all the doctors could do was give him opium for the pain, and wait. The young man was 24 years old; he was survived by his mother and sister. His funeral was held at home. The newspaper noted, “The floral offerings were profuse, and of rare designs, typical of the life of the deceased.”

About 1885, John Waller enlarged the house, outward from the center, adding rooms on the north and south sides. By 1892, the house was quite full of Wallers: John & Julia, Winifred, Julius, John C., Percy, Reginald, Earll and Harcourt (“Harry”).

In 1896, Julia Earll Waller died of pneumonia, leaving John as the single parent of seven children. Three years later, Reginald “Reggie” Waller, ten years old, fell into Skaneateles Lake while fishing from the steamboat dock, and drowned. He was remembered as a lively, cheerful lad.

In October of 1905, Winifred Waller, John and Julia’s only daughter, married William Tallcot Thorne at St. James’ church; the groom, a member of one of the village’s most prominent families, would make his way in the world as a paper manufacturer, a farmer, an importer and breeder of Shropshire sheep, a trustee of the Skaneateles Savings Bank and a director of the Skaneateles Creamery Company. A wedding supper was held for the bridal party at the Waller home, which was decorated with palms, chrysanthemums and carnations.

On the evening of Christmas Day of 1906, after a day spent with his family, John Waller, 55, died suddenly at home of heart failure. He was survived by his daughter Winifred Thorne, and five sons: Julius, John C., Percy, Harcourt and Earll. The funeral was held in the Waller home.

John E. Waller left his sons two legacies, one good, one not so good. The money was there for five college educations: Julius Earll Waller, Williams College, ’03; John C. Waller, Princeton, ’06; Percy Waller, Princeton, ’10, Harcourt Waller and Earll Waller, Princeton, ’14. The other portion of their inheritance was poor health. In 1910, John C. Waller died of diabetes, at the home of his sister, at the age of 26. In 1926, Percy Waller died of a heart attack at the age of 39. In 1931, Julius Waller died of pneumonia in Schenectady at the age of 48. Harry and Earll Waller remained healthy, but had moved to Augusta, Georgia, by 1918.

In June of 1932, William Tallcot Thorne died at the age of 55. Almost 30 years later, on March 15, 1962, Winifred Thorne died at the age of 83, in the house where she was born.

The house now stood empty. In Architecture Worth Saving in Onondaga County, the house was described thusly:

“This is a house redolent of the turn-of-the-century: rather heavy, rather somber and rich as plum pudding; it is painted a now-faded deep red, with blue-green trim. Currently vacant, one can still hear the creaking of wicker rockers on its verandah where, among hanging baskets of ferns, one can visualize Gibson Girls and their white-flanneled beaus. This was the residence of a large family of local prominence and comfortable means in the pleasant community of Skaneateles just prior to the advent of the Twentieth Century.

“The interiors are equally imbued with turn-of-the-century character. A large reception hall is dominated by a broad staircase with paneling and enclosing screen of Cherry, handsomely designed. The original architect’s drawing of this as well as for the general remodeling are believed to be somewhere extant in the family possessions, although his name is forgotten. Fireplaces vary in period from the simpler white marble models in the older parlors to the elaborate paneled, tiled and multi-mirrored triumphs of the Nineties, adorning the reception hall and new parlor.

“While this cannot be considered unusually distinguished architecture, it is representative of the more restrained taste of an era not remembered for restraint, and is a house of great period charm which, fortunately, has been preserved through several generations of hostile reaction to a time when more objective appreciation may be possible. As this property is currently for sale, it is hoped that it may find an owner sympathetic to its intrinsic character, returning the rockers and ferns to the verandahs.”

Unfortunately, a fire “of unknown origin” gutted much of the interior the night of October 14, 1964. Some of the interior elements of the house were saved, but overall the fire and water damage was too extensive and restoration was beyond the resources of the estate’s heirs. And so another home in Skaneateles passed into history, but lives in memory.

* * *

Notes on Dr. Benedict

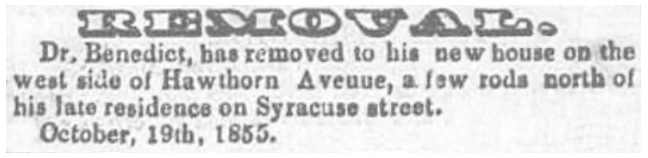

In October of 1855, Benedict placed an advertisement in the Skaneateles Democrat noting that he had moved to a new house “on the west side of Hawthorn Avenue, a few rods [about 50 feet] north of his late residence on Syracuse street.”

This threw me; now there were two Benedict houses to consider, and this ad is the only mention of a “Hawthorn Avenue” in Skaneateles I have ever seen. Perhaps, because the ad was placed on a recurring basis, it was a reference to his medical practice, which he moved out of his home to another house just north, and that the Benedict house built in 1846 is the one mentioned in later accounts. Short of holding a séance, I’ll have to live with that idea.

* * *

When Dr. Benedict died in Syracuse on January 7, 1885, at the age of 71, a fellow officer recalled, “Dr. Benedict was a good surgeon. I remember at one of the battles of Port Hudson, when he was doing field hospital duty, seeing him standing by a hogshead of arms, which he and his assistants had cut from the wounded.” Another said, “I remember one expedition when we were on the Red River. When the scouting party returned to camp late at night, tired, wet and hungry, they found that Dr. Benedict had prepared a large kettle of hot soup, and the boys were not slow to appreciate the kindness.”

* * *

Dr. Benedict was buried in Lake View Cemetery. Years later, while visiting Henry Kelso in Syracuse, Benedict’s granddaughter, Elizabeth Holley, asked if there was anything she could do for him. He said, “When I die, just bury me at the feet of my beloved master—Doctor Benedict.” His wish was respected. In 1916, the body of Henry Kelso was buried at the foot of Dr. Benedict’s resting place, with a simple stone marked “H.K.” On Memorial Day of 1942, Elizabeth Holley placed an American flag on his grave.

* * *

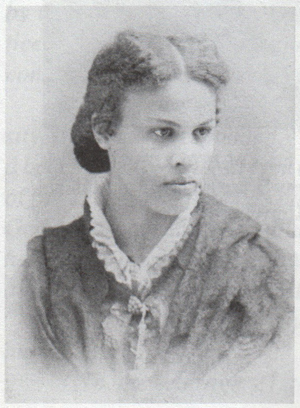

After the Civil War, Dr. Benedict moved to Syracuse and it was there he found a home for Henry Kelso, still a boy, at the home of the Rev. Jermain Loguen, an abolitionist who had escaped slavery, and his wife Caroline. Their home in Syracuse had been an important link on the underground railroad, sheltering hundreds of escaped slaves as they were moved to safety in Canada. Benedict knew them as their family physician and as a member of the Freedmen’s Relief Agency, which helped freed slaves find employment.

The Loguens’ daughter, Sarah, had helped to treat the injuries and illnesses the slaves suffered as a result of their enslavement or escape. When she decided to become a physician, she told Benedict and he agreed to tutor her. She shadowed him for five months and with his support she entered Syracuse University’s College of Medicine in 1873.

In 1876, Sarah Loguen became the first woman to gain an M.D. from Syracuse University, and the fourth African-American woman to become a licensed physician in the United States. It was Dr. Michael Benedict who handed her the diploma.

* * *

Selected Sources

“Letter from the 75th Regiment, N.Y.S. Volunteers” by Michael D. Benedict, Skaneateles Democrat, November 27, 1862

Photo of Dr. Michael D. Benedict courtesy of the New York State Military Museum

Atlas of Onondaga County, New York (1874) by Homer D. L. Sweet

“Notes of Other Days in Skaneateles,” written for the Skaneateles Democrat in 1876 by Rev. William M. Beauchamp

“Surgeon of the Seventy-Fifth,” News-Bulletin-Auburnian, January 8, 1885

Skaneateles: History of its Earliest Settlement and Reminiscences of Later Times (1902) by Edmund Norman Leslie

“Sudden Death of a Man [John E. Waller] Who Had Done Much for Skaneateles,” Auburn Citizen, December 20, 1906

“Obtained from Mrs. Holley, August 29, 1937,” in Skaneateles History by Sedgwick Smith, an unpublished draft, typed by Beth Batlle, indexed by Laurie Winship.

“Grave of Grandfather’s Negro Servant to Be Decorated May 30 by Mrs. Holley,” Skaneateles Press, May 15, 1942

“Drinking Down the National Debt” in The Social History of Bourbon (1963) by Gerald Carson

Architecture Worth Saving in Onondaga County (1964) Syracuse University School of Architecture & New York State Council on the Arts

“Police Seek Cause of Thorne Fire,” Skaneateles Press, October 16, 1964

“Razed Thorne Mansion Leaves Mementos of Past,” Marcellus Weekly Observer, March 25, 1965

“A Historic Lakeview Grave” by Don Stinson, Skaneateles Press-Observer, May 27, 1987

“All the Heaven I Want: The Life of Dr. Sarah Loguen Fraser” by Susan Keeter in Three 19th-Century Women Doctors (2007)

And, of course, the always indispensible Fulton database and Ancestry.com.

I have always been intrigued by this postcard, but only yesterday learned that it was published by the Paul C. Koeber Co. (PCK) in New York City.

The Metropostcard site notes that Koeber, “Published national view-cards and illustrations in chromolithography and in black & white. Much of their color work has a dark heavy feel to it because of the many thick layers of ink they used.” Koeber postcards were printed in Kirchheim, Germany; this one was published for The Smoke House in Skaneateles, and posted in 1907.