I confess to some personal confusion regarding what came to be known as the Mott Cottage, because there were two Lydia Motts and our own Lydia lived in three different cottages.

First let us respectfully dispense with the other, and perhaps more famous, Lydia Mott (1806-1875), a Quaker teacher who was active in the movements to gain the vote for women and end slavery. Our Lydia Mott (1775-1862) was a Quaker teacher who founded a boarding school for young women, and was a strong advocate of education for women. Fortunately, she was known more often as Lydia P. Mott, her middle name being Philadelphia, in honor of the new home her parents, Joseph and Sarah Stansbury, had established in America. (Some accounts place her birth in the mid-Atlantic Ocean, while her parents were enroute to Philadelphia.)

In 1795, Lydia married Robert Mott; ten years later, she was widowed and left with four children. Between 1812 and 1816, three of the children died, leaving her with just her son Arthur.

In 1818, Lydia and Arthur came to Skaneateles. By the next year she had established the Friends Female Boarding-School, more familiarly known as “The Hive.” Mott and her assistants taught needlework, arithmetic, grammar, geography, history, rhetoric, logic, bookkeeping, philosophy and mathematics, as well as French and Latin.

Mott sold the Friends Female Boarding-School in 1823. But she remained in Skaneateles and continued her involvement with the school’s students. A friend wrote, “The little cottage where she lived, nearly opposite the Friends’ meeting-house, was then a lovely place, with its porches covered with fragrant honeysuckles, and two sides of the house surrounded by a flower garden.”

This was Lydia Mott’s first cottage, but not the Mott Cottage. This cottage was located at what is today the corner of West Lake and Benson Roads. After selling the school, she moved closer to the Village. In “The Early Quakers of Skaneateles,” published in the Skaneateles Free Press of January 29, 1897, Mary Elizabeth Beauchamp noted, “Mrs. Mott, after leaving her pleasant, rose-embowered little abode opposite the ‘Hive,’ built the cottage which was afterwards owned by Frances and Edward Potter on the site of the present ‘Mingo Lodge.’ This was her second cottage, but not the Mott Cottage.

(At the time of Miss Beauchamp’s writing, Mingo Lodge was the former Daniel Robbins estate, renamed by its new owners in 1895. The main house eventually became known as Westgate, and “The Annex,” built for the family’s children, took the name Mingo Lodge. This latter-day Mingo Lodge, designed by architect Charles Follen McKim in 1878, was demolished in 2016.)

In later years, Lydia P. Mott left Skaneateles briefly, moving to Cincinnati, Ohio. But she returned to Skaneateles, living in what was long known as Mott Cottage, where she spent her last years.

Mott Cottage

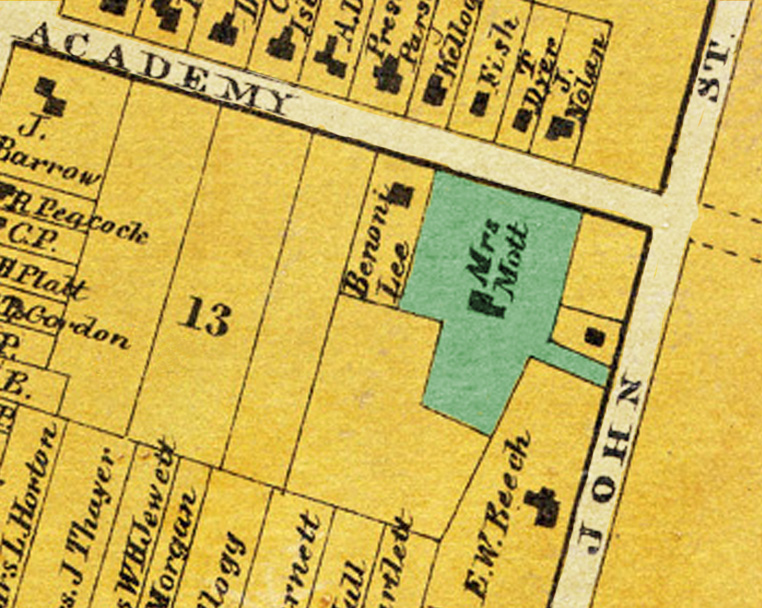

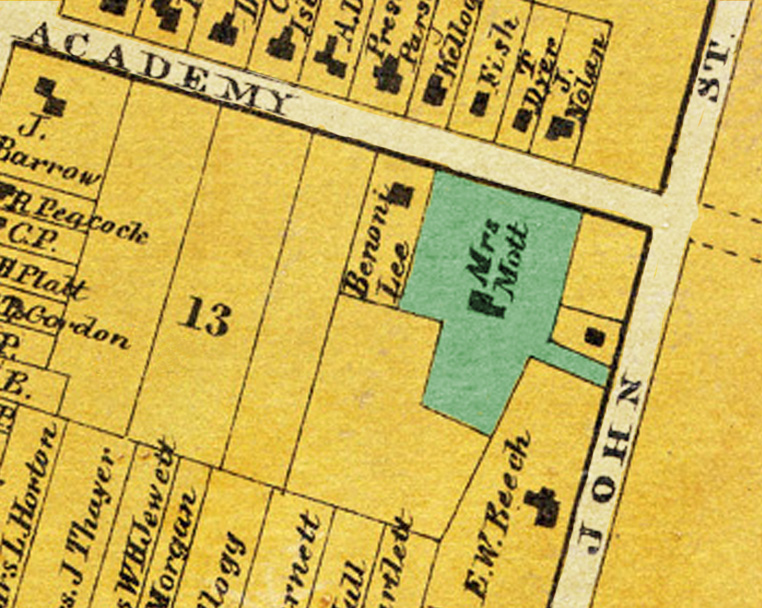

Seen on the 1856 map below, the Mott Cottage was at the top of Leitch Avenue (then known as John Street) at the corner of Academy Street.

In the Skaneateles Press of January 23, 1936, historian Fred Humphryes described the cottage and his childhood under its roof:

“After Mrs. Mott’s death, my father [John Humphryes] rented the place, and we lived there for six years. In this house my youngest sister [Alice] and two brothers [Harold and Willie] were born and where one of my brothers [Willie] died.

“The Mott cottage was a long, rambling story-and-a-half house. It stood where the dwelling of Mrs. Lillian Palmer stands. On the first floor to the west was the parlor, with a bedroom to the south, both rooms opening into a hall which extended north and south clear thru the dwelling, and opening onto a porch in the rear, this porch overlooking the lake. On the east of the hall was a large living room facing Academy street and to the rear of this was a bedroom, and next east of the living room was the kitchen, and from this extended a long storeroom and woodshed, on the upper story of the house were two bedrooms on each side of the stairway.

“Between the house and Academy street was a ravine with a brook running through it, on either side of this ravine were a row of stately maple trees. This ravine has now been filled in, the cottage demolished, and nothing remains of the dear old place but the barn, and that has been transformed into a garage. Extending south from the back porch was a pair of old-fashioned cellar doors where we children used to slide down, and what great times we had there. From this back porch I remember watching a torch-light procession as it passed along Genesee street. This was during the Grant and Colefax campaign. It was a pretty sight, watching the flicker of the lights through the trees.”

“My memory takes me back, at times, to the old cottage, and the trundle bed in which I used to sleep in what we called the hall bedroom. In the summer the brook had a great attraction for me. I would go down and lift the stones to see the crabs scuttle from under them.”

In her last years, Mrs. Mott was confined to her cottage. Susan Kellogg Lee, the wife of Benoni Lee, lived just around the corner on Academy Street. She, like many of Mrs. Mott’s friends, would visit her almost every day and read aloud to her, to help pass the time.

Lydia P. Mott died on April 15, 1862, at the age of 87. An obituary in the Friends’ Intelligencer noted:

“She was an example of plainness and simplicity; and the subject of the best education of woman occupied much of her time and thoughts. The wrongs and injuries of the poor Indian claimed her sympathy and care. For the imbruted slave she was an earnest advocate, the latest effort of her pen, only a few months since, being an encouragement to those who were laboring to affect his emancipation. She bore the vicissitudes of her changeful life with an uncomplaining spirit, in the fulness of faith that goodness and mercy would continue to follow her all her days, and her end was signally marked with peace.”

Three years after Mrs. Mott’s death, Susan Kellogg Lee anonymously submitted a poem, “The Maples of Mott Cottage,” to the Skaneateles Democrat:

“They grew in the forest tall and fair,

Until man the destroyer came,

Felling their brothers for light and air,

And to nourish the household flame.

Musing a while on the hill, he stood,

Watching the day’s decline;

Why do I fell these lords of the wood,

Planted by Hand divine?

Sickly exotics from sunnier climes,

These natives can never replace;

Leaves softly murmuring like evening chimes,

It seems like a hallowed place.

A group of trees by this purling brook,

A cottage would shade and adorn,

Peace for a pilgrim in yon quiet nook,

Repose for the weary and worn.

Bared to the sun, cheered by the breeze,

Half a century of seasons have sped.

The maples now are grand old trees,

And the woodman who spared them is dead.

They catch the first gleam of morn’s early light,

See the shadows steal over the lake,

The sun’s parting rays linger at night,

Tinge with gold the wood and the brake.

Here may life close in quiet and ease.

Weary the path I have trod,

I can list to the murmur of the trees

And silently worship God.

Hushed the lone heart, its pilgrimage done,

The breezes sigh mournfully by;

To the bourn that’s returnless the mother has gone,

The son among strangers to die.”

Writing in 1897, Mary Elizabeth Beauchamp noted that Mott Cottage “has been pulled down within a few years.”

Writing in 1936, Beauchamp’s nephew, Fred Humphryes said, “The dear old place is gone, and I often wonder if the home we build today are any more comfortable, or look any better than the well-kept, rambling old cottages of our childhood. What a beautiful place the old Mott Cottage would be today, with the ravine and brook, a rustic bridge across it with a well-kept lawn and flower beds. Certainly it would be the delight of all beholders.”

***

Notes:

For more on Lydia P. Mott: “A Powerful Influence in Disseminating Knowledge: Lydia Philadelphia Mott and the Friends Female Boarding-School in Skaneateles, New York” by Jana A. Bouma

Regarding the torchlight parade, in 1868, Ulysses S. Grant and Schuyler Colfax successfully ran for the offices of U.S. President and Vice-President.

For more on Mingo Lodge: https://kihm6.wordpress.com/2010/04/17/the-robbins-estate/

For more on Benoni Lee: https://kihm6.wordpress.com/2023/01/16/benoni-lee-our-sphinx/

Susan Lee’s poem was originally published in the Skaneateles Democrat, December 7, 1865. The poem’s final line is a reference to the death of Lydia’s son, Arthur Mott. He was a bright lad and successful in business; he established a woolen mill in Mottville, which was named for him, but later in life suffered grave financial reverses and succumbed to alcoholism. He moved to Toledo, Ohio, and died there in 1869, “among strangers.”