Photographs by Robert Furth, with thanks to David Furth.

Month: March 2014

On the Sanity of Ellen Dodge

Ellen Dodge (in white) with her niece and sister in 1902

Born in 1830, Ellen Miranda Wheaton became the third wife of Harrison B. Dodge of Skaneateles in 1859. Mr. Dodge was the longtime editor and publisher of the Skaneateles Democrat, and Mrs. Dodge lived quietly in his shadow. But in 1898, Harrison Dodge “passed peacefully away into the Great Beyond,” in the words of local eulogist Edmund N. Leslie, and the next year Mrs. Dodge lost her brother as well, Gerrit Wheaton of Cleveland, Ohio.

Harrison Dodge’s estate was modest: the couple’s house on East Academy Street and some personal effects. Gerrit Wheaton, on the other hand, was a millionaire; he left the majority of this estate to his widow, but set aside $100,000 for his sister, who received the bequest in 1902. Wheaton had done well in his business dealings, and was the brother-in-law of Henry Flagler, the co-founder of Standard Oil with John D. Rockefeller. And so a sizable amount of Ellen Dodge’s fortune was in Standard Oil stock.

Mrs. Dodge had written a will in 1901 leaving everything to her relatives. But after her windfall in 1902, she decided to write a new will including bequests to friends and charities; this will was written and filed in 1904. Her relatives, however, seeing how the size of the pot had grown, decided they wanted it all.

They began by having Mrs. Dodge declared incompetent, with a nephew in New York City put in charge of her spending, which had included “so much money on bonnets and favored relatives.” They cited as an example Mrs. Dodge’s inviting 50 friends to tea, surely a sign that she had taken leave of her senses. Her next of kin, willing to be quoted in the newspaper, baldly said they would get more if she spent less.

Ellen Dodge died on Christmas Day, 1907, and the free-for-all began. Her step-grandson, Harrison A. Dodge, demanded her furniture, saying it had only been willed to her for her lifetime, and should now be his. He then sued the estate for $3,000, saying that property of Harrison B. Dodge which was willed to Mrs. Dodge would have been worth $3,000 had she retained it. He neglected to note that after the property in question had already been auctioned off for $125, he had accepted the check from Mrs. Dodge, and cashed it.

Mrs. Dodge’s new 1904 will included bequests of $5,000 to St. James’ Episcopal Church, and bequests of $4,750 each to the Rev. Frank Nash Westcott and the Skaneateles Library Association. The relatives sued, saying that Mrs. Dodge had lost her marbles before the 1904 will and thus had not been of sound mind. Five of the village’s six attorneys became involved in the case, and set their meters running.

The legalities consumed all of 1908 and dragged on into 1909. And while all this went on, the value of Standard Oil stock soared. In late 1909, the relatives were informed that if they won their suit and settled under the terms of the 1901 will, they would actually receive less money than if they lost and settled on the terms of the 1904 will. Suddenly – and I know this will be hard to believe – they dropped their suit. And the attorneys presented bills totaling $13,500.

The attorneys certainly could have built a monument to Ellen Dodge, but did not, and she is remembered today only by a pew at St. James’.

* * *

Pew photo by Lauren Mills Wojtalewski

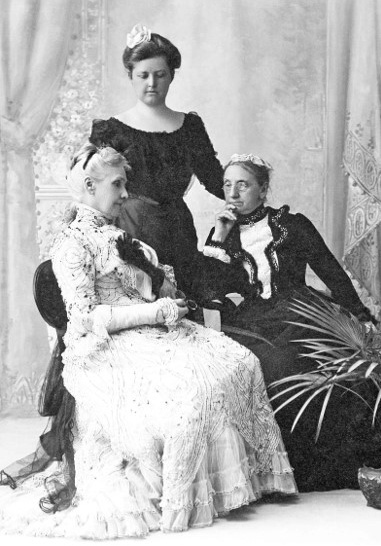

Robert Minturn Grinnell

The Grinnell family came to Skaneateles in 1877, and brought with them quite a history.

Robert M. Grinnell was the son of Henry Grinnell, of the Grinnell, Minturn & Co. shipping line, owners of the famous Flying Cloud clipper ship. Robert grew up in the shipping business, and was member #4 of the New York Yacht Club. In 1852, he shipped his sloop Truant to England and won seven races out of eight, prompting the English to put the boat in its own category so it would have nothing to race against.

In 1857, Robert Grinnell was living in Liverpool, England, and active in shipping. And it is here that his story takes an interesting turn.

At the time, 60% of the cotton grown in the American South was being shipped across the sea to Liverpool, and thence to the textile mills of Lancashire. This was a huge business, with principals on both sides of the Atlantic making enormous sums of money, and thoroughly dependent upon one another. When the American Civil War broke out, the British stance was officially neutral, but the city of Liverpool was ardently pro-Confederacy. The fortunes of its shipping and textile industries were at stake, and they faced ruin if the Union blockade of Confederate ports was successful.

So, although from New York and living in England, Robert Grinnell was surrounded by Confederate sympathizers. (A literary note: Just as Kenneth Robert’s Rabble in Arms (1933) and Oliver Wiswell (1940) help one to understand the feelings of colonists who remained loyal to the Crown during the American Revolution, so Jules Verne’s The Blockade Runners (1871) helps one to understand how the British, merchants in particular, viewed the American Civil War.)

One of Grinnell’s business associates in Liverpool was Charles Kuhn Prioleau, who arrived in Liverpool in 1856 from Charleston, S.C., to serve as the resident manager for the shipping firm Fraser, Trenholm & Company. Prioleau, essentially, went for broke betting on the Confederacy. Even before the war began, he was sending British artillery pieces to Charleston, one of which was aimed directly at Fort Sumter, the Union stronghold in Charleston harbor.

When the war began in earnest, Prioleau became the primary financier and blockade runner for the Confederacy. He built ships at his own expense, had those of the firm already in service transferred to British registry, and ran cotton through the blockade, “laundering” it in Nassau or Bermuda before its arrival in Liverpool, and sending his ships back to Charleston loaded with gunpowder and weapons, and whatever else the South required.

Robert Grinnell, meanwhile, dissolved two shipping partnerships he had in London, and sailed for New Orleans, where he would enlist in the Confederate army. He was no doubt encouraged by his English wife, Isabella Musgrave, who he married in 1860. Although English, she volunteered to serve as a nurse at a hospital in Richmond, Virginia. Her son from an earlier marriage, Linus Musgrave, went into the Confederate navy. And in June of 1861, her husband was mustered into service as a 1st Lieutenant in Maj. Chatham Roberdeau Wheat’s Battalion, also known as the Louisiana Tigers.

Wheat’s Battalion traveled north to Virginia just in time to participate in the First Battle of Bull Run, and served in “Stonewall” Jackson’s Valley Campaign. At the Battle of Front Royal on May 23, 1862, Lt. Grinnell was wounded in the hand, losing two fingers, and captured. He was sent as a prisoner to Washington D.C. in July, and then to Fort Monroe, Virginia, where he was exchanged for a Union officer on August 5, 1862. After his exchange, he was promoted to Captain, then Major, while serving on the staff of Gen. Henry Heth in the Army of Northern Virginia, commanded by Gen. Robert E. Lee.

Writing to Charles Prioleau from Richmond in June 1863, Major Grinnell said that he was still confident of victory, but added that he had lived on bacon and corn for the last year.

Also in Richmond, Isabella Grinnell was looking for work. On April 8, 1863, she wrote to Jefferson Davis, the president of the Confederacy, as follows:

“In consequence of the Hospital being closed, in which I was employed, and as I came 5,000 miles in hopes of being of service to this Confederacy, I do not wish to remain idle. I therefore tender to your Excellency the use of my services, to be employed in any way you may see fit. I should be willing to undertake to carry dispatches to be delivered on this continent or in Europe, and I feel confident that I should be able to deliver them to whomever they might be sent… I will only add that if I am employed in any way, I will not fail, for I do not know the word.”

In October of 1863, the diary of Samuel Pearce Richards, a bookseller in Atlanta, Georgia, notes:

“Tonight we went to Mr. Root’s to sing and found there Mrs. Grinnell, an English lady who has come to our country as a ‘Florence Nightingale’ and has made herself very useful in the hospitals near the battlefields. She is an educated lady and a very entertaining talker indeed and we all enjoyed her society for an hour or two very much, singing to fill up the pauses. Mr. Grinnell is an officer in the Confederate Service.”

Sidney Root, at whose home Mrs. Grinnell was staying, was a merchant who began a career as a blockade runner at the personal request of Jefferson Davis, a close friend. Root opened a shipping office in Charleston and another in Liverpool. Root’s partner, John N. Beach, managed the office in Liverpool and became a British subject. At the peak of their success, Root and Beach had a fleet of 20 British steamers. It seems likely that these connections are what brought Mrs. Grinnell to Root’s home, and perhaps it was Jefferson Davis himself who suggested it.

History gives us one more glimpse of Mrs. Grinnell: In May of 1864, the journal of Rachel Wilson Moore notes that Isabella Grinnell was a passenger on a boat bound from the island of St. Thomas to the island of Bermuda. With or without a message from President Davis, she was most probably on her way back to England. And there, I lose track of her.

At the end of the war, many secessionists with wealth and European connections chose to take advantage of them. There was, after all, talk of hanging secessionists for treason. Charles Prioleau, for example, had become a British subject in 1863, and never returned to Charleston, never saw his family again. Robert Minturn Grinnell was said to have spent considerable time in Europe after the war. Whether he divorced Isabella, or was widowed, I do not know.

But in 1873 he was back in the United States, marrying Sophia “Sophie” Van Alen of Newport, Rhode Island; in 1876, their daughter Josephine Lucy “Daisy” Grinnell was born in New York City.

In 1877, the Grinnell family came here and bought a large plot of land on West Lake Street, essentially all of the land between today’s Westgate estate and the Skaneateles Country Club. They sold the northern half of the land to Sophie’s sister, Lucy Hurd, wife of Dr. Samuel Hurd, and both families built houses they would use as summer residences. (The Grinnell property eventually became C.D. Beebe’s “Lone Oak” estate, and has since been owned by the Foley, Winkelman and Ruston families. The Hurd property was later owned by the Fitzgerald, Hazard and Parker families.)

Robert and Sophie Grinnell summered in Skaneateles, and spent their winters in Europe. In 1898, they went to Nice, France, to the villa of Robert’s sister, Sarah (Grinnell) Watts, where Robert became ill and died. He was buried at the Cimetière des Anglais Caucade (British Cemetery) in Nice. Sophia Van Alen Grinnell died in 1916 and is interred in the Hurd family vault in Woodlawn Cemetery, Bronx, New York.

Robert Minturn Grinnell is remembered today in Skaneateles by the chancel area of St. James’ Episcopal Church, enlarged in his memory in 1901, and by the “school of Tiffany” window put in place at that time, both gifts of Sophie Van Alen Grinnell.

Nicholas and Eleanor Roosevelt

Nicholas Latrobe Roosevelt (1847-1892) was the son of Samuel and Mary Jane (Horton) Roosevelt, of New York and Skaneateles, and the grandson of Nicholas J. and Lydia (Latrobe) Roosevelt of Skaneateles. He was born here in June of 1847, and grew up living in New York City and summering in the village. His younger brother, Samuel Montgomery Roosevelt, also had a long association with the village, buying the De Zeng mansion in 1899 and renaming it Roosevelt Hall.

An 1868 graduate of the Naval Academy at Annapolis, Nicholas Roosevelt served with the U.S. Navy in the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, and in 1871 was a part of the U.S. expedition to Korea. This began as a diplomatic mission, but evolved into something more bellicose when Korean shore batteries fired upon two American ships. While the Korean cannons were primitive and their shots went astray, the Americans, in the person of Rear Admiral John Rodgers, demanded an apology, didn’t get one, and so attacked the Korean forts.

Lieutenant Roosevelt, who was serving as Master on the U.S.S. Alaska, commanded a group of gunboats which shelled the forts from the water while 600 sailors and Marines landed and stormed the forts on foot. The Koreans were armed with matchlock muskets, and when these proved to be ineffective, they threw rocks. Really. After a short battle, five Korean forts had been taken and 246 men were dead, of whom 243 were Korean. When Admiral Rodgers tried to use 20 wounded Korean prisoners as a bargaining chip, the Koreans said, “Keep them. They are all cowards.” Lt. Roosevelt was “creditably mentioned in dispatches,” but was not one of those decorated for heroism.

In 1874, Nicholas left the Navy and settled in New York City. And on April 14th of that year, he married Miss Eleanor Dean, starting the whole ‘Eleanor Roosevelt’ thing.

This story, in fact, offers us an opportunity to sort out the Eleanor Roosevelts of Skaneateles, not counting Eleanor (Roosevelt) Roosevelt, wife of F.D.R., America’s longest-serving First Lady, who visited here, but wasn’t really ours. As noted above, Nicholas began the confusion, inadvertently I am sure, when he married Eleanor (Dean) Roosevelt. Their son, Henry Latrobe Roosevelt, threw us all a curve ball when in 1902 he married Eleanor (Morrow) Roosevelt, and, as was their right, upon the birth of a daughter in 1915, Harry and Eleanor named her Eleanor Katherine Roosevelt. So if a researcher looks for an Eleanor Roosevelt who summered in Skaneateles, he or she quickly finds three.

While I’m at it, Skaneateles also had three Henry Latrobe Roosevelts: The first was the son of Nicholas J. and Lydia; he was born in 1811, gave St. James’ Episcopal Church an organ in memory of his mother and donated the Nicholas Roosevelt stained-glass window in memory of his father. The second Henry Latrobe was the son of Nicholas L. and Eleanor, born in 1879 and known as “Harry;” he became the Asst. Secretary of the Navy and owner of Roosevelt Hall from 1920 to 1936, having inherited it from his uncle, Samuel Montgomery Roosevelt. The third was Henry Latrobe Jr., the son of Henry L. and Eleanor; he was born in 1910, went by “Troby,” spent time here in his boyhood and in August of 1916, caught and survived polio during an epidemic that took the life of the St. James’ Rector’s wife, Mary Hewlett.

But back to Nicholas. In New York, he became connected with the business of fire insurance while serving as Secretary of the New York & Boston insurance company, and in 1884 became a principal in the insurance firm of Roosevelt & Boughton. He was a member of the Union Club, the Down Town Club, the Loyal Legion, and the Essex Country Club in Morristown, New Jersey, where the family made its home. It was said that he would sit on the veranda of the country club and swap stories about Asia with some of the other well-traveled members.

Nicholas Roosevelt died of pneumonia at his home in New York in 1892; the funeral was held at his residence and his body was brought to Skaneateles for burial. He was just 45 years old. Eleanor Dean Roosevelt outlived her husband by more than 40 years. She summered in Skaneateles with the children: Harry, Louisa and Guy Nicholas. She was listed in the Social Register of New York, and known in Skaneateles for giving dinners and bridge parties. Her arrivals and departures were noted in the Skaneateles Press. Eleanor later wintered in Charleston, South Carolina, where Guy Nicholas’ wife, Emily, had family connections and a plantation, and “Nick” and Emily Roosevelt eventually owned a plantation of their own.

Eleanor Dean Roosevelt died at her daughter Louisa’s home in New York City in 1933. Her funeral service was held here at St. James’ and she was buried in Lake View Cemetery, next to the grave of her husband.

Nicholas and Eleanor Roosevelt are remembered in Skaneateles by pew number 17, on the west side of the nave, at St. James’. The pew was most probably endowed by their son, Henry Latrobe “Harry” Roosevelt, who was summering in Skaneateles at Roosevelt Hall in the early 1930s, and by their two other children, Louisa Roosevelt Bainbridge-Hoff of New York, and G. Nicholas Roosevelt of Philadelphia and South Carolina.

* * *

Pew photo by Lauren Mills Wojtalewski

The Perfect Job

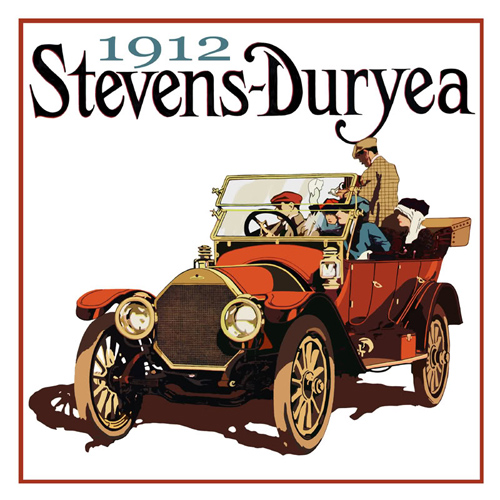

On Sunday afternoon, June 30, 1912, John Dean of Auburn offered two friends from Skaneateles a ride in the country in a new Stevens-Duryea touring car, with a six-cylinder engine that could produce speeds of up to 60 miles per hour.

On Sunday afternoon, June 30, 1912, John Dean of Auburn offered two friends from Skaneateles a ride in the country in a new Stevens-Duryea touring car, with a six-cylinder engine that could produce speeds of up to 60 miles per hour.

William Topp, a shoemaker, and J. Charles Stephenson, Jr., son of the proprietor of the Skaneateles Free Press, were seated in the back when Dean rounded a curve outside of Cato, saw a horse and buggy approaching, swerved and hit a telephone pole head-on. The pole snapped like a match stick; the car flew into the next pole and flipped. Dean’s passengers “were hurled from the car as though shot from a monster slingshot, turning over and over as they went.”

The Auburn newspaper reported, “Former Sheriff Jesse Ferris of Cato who lives a mile and a quarter distant from the scene of the tragedy said he plainly heard the twang of the impact when the iron monster struck the telephone pole.”

Topp and Stephenson were dead at the scene, and Dean was critically injured. When John C. Stephenson, Sr., was found at the Packwood House and told of his son’s death, he fainted and fell to the floor in the lobby.

I will let the Auburn Journal tell the rest of the story:

“For three days it was believed Mr. Dean would die from his injuries, but although that was less than a month ago, he showed no ill effects of the accident to-day.

“‘Never any more fast driving as long as I live,’ remarked Mr. Dean as he stopped to receive congratulations from friends on Genesee Street. ‘I’ll never drive faster than six miles an hour. I did not realize the high speed when the accident occurred.’

“Mr. Dean is planning to spend the next two months at the home of his aunt… He said that by that time he would be able to resume his duties as an auto salesman.”