I was talking about chess with a friend over lunch at the Sherwood Inn, in Skaneateles, N.Y., and afterwards it occurred to me that we couldn’t have chosen a better spot for the conversation.

In the late 19th century, the New York State Chess Association (NYSCA) held mid-summer meetings at places like Keuka Lake, the Thousand Islands and Saratoga Springs. For city players, these tournaments were a welcome tonic, an escape to cooler, leafier climes. Beginning in August of 1889, Skaneateles was the host for four of these summer meetings, with the tourney headquartered at the Packwood House (today’s Sherwood Inn), where they paid $1.50 a day for their room and board.

The power players came from New York City and Philadelphia, the latter members having joined the NYSCA when the New York and Pennsylvania associations merged. More than 40 men were entered, and sorted by ability into four classes. Local entrants included attorney George Barrow, merchant Benjamin Petheram, William Shotwell (for whom Shotwell Park is named), and H.B. Dodge, the editor of The Skaneateles Democrat.

Spectators paid $1 to watch the games; ladies were admitted for free. The New York Sun, the New York Herald and the Associated Press had a telegraph operator in place to report the result of each game.

Solomon Lipschütz (1863-1905)

After the first evening’s games in 1889, Solomon Lipschütz, the reigning New York State Champion, relaxed by playing 11 informal games simultaneously — winning six, drawing three and losing two. Lipschütz would become the U.S. Champion in 1891 and hold the title until 1894. But at the end of the four-day 1889 tourney, the overall winner was William DeVisser of the Manhattan Chess Club.

The NYSCA returned to Skaneateles three more times. James Moore Hanham of the Manhattan Chess Club won the 1891 tourney.

William Pollack (1859-1896)

A notable entrant in 1891 was an English-Irish-American-Canadian player, William Pollock, a winner of the Irish Championship, and at the time a resident of Baltimore. Pollack was a colorful character known for enjoying the creation of brilliant combinations more than actually winning. Howard J. Rogers, Secretary of the New York State Chess Association, described his first meeting with him as follows:

“As an added attraction to the midsummer meeting of the Association at Skaneateles, N.Y., we hit upon a match between the New York State Champion, Eugene Delmar, and Mr. Pollock, the Champion of the South. I conducted the correspondence, which was very pleasant, and awaited with much interest my first meeting with Mr. Pollock. The match was to begin on Monday, and up to Sunday noon we were uncertain of the whereabouts of the Southern Champion.

“About five o’clock, a few of us were sitting on the broad piazza overlooking the beautiful waters of Skaneateles Lake, when a dusty figure in a brown suit, freckled face and wealth of reddish chestnut hair, approached the hotel. ‘Pollock,’ we shouted in a breath, ‘where on earth did you come from?’ ‘Well, you see,’ said he, shaking hands all round with beaming cordiality, ‘I brought up in Syracuse early in the morning; I really couldn’t spend the day loafing around there, so I thought I would take a bit of a tramp across the hills and tone myself up a little for the match.’ His ‘bit of a tramp’ was a hard walk of over 20 miles in a hot August day. Pollock lost that match, by the way, but took his defeat with the utmost good humour.”

Wilhelm (William) Steinitz (1836-1900)

Also along that year, to report on the tournament for the New York Tribune, was William Steinitz, then the game’s World Champion, a title he held from 1886 to 1894. In Germany, the Deutsche Schachzeitung of September 1891 reported:

“Steinitz played two blindfold games against Hodges and Rogers and won them both, the first one even after a brilliant Queen’s sacrifice.”

In August 1892, Walter Penn Shipley and Herman G. Voight of Philadelphia’s Franklin Chess Club tied for top honors. In 1895, S. W. Bampton, also of the Franklin Chess Club, was the winner of the 1895 tournament. That year, William Duval of the Brooklyn Chess Club wrote commentary in verse, including these lines that indicate William DeVisser, the 1889 tourney winner, was a regular summer resident:

We found the lake as fairy like

And sparkling as before

Responsive to the singing throng

Or gently dipping oar

Romantic drives through thrifty farms

Brought changes ever new

Of fragrant hills and heavenly skies

And limpid waters blue

No wonder that for seventeen years

DeVisser here hath come

To build his stalwart six feet two

And find a summer home

Obsequious maids in wonder stand

With condiments arrayed

While Vis with deftly practiced hand

Imperial salads made

And when he called for ginger ale

Or gave a wink for wine

See how they rush and bring it cool

And pop it off quick time

To gild the closing hours of chess

He played a score of games

And still his prestige and success

Inviolate maintains

Among the New York State Champions who played in Skaneateles were DeVisser, Lipschütz, Eugene Delmar, N.D. Luce and Albert B. Hodges. From that group, two also became U.S. Champions: Lipschütz and Hodges.

Albert B. Hodges (1861-1944)

Albert B. Hodges (1861-1944)

Of them all, Hodges is perhaps the most fascinating, a chess player with a double life. In his public career, he won the U.S. Championship in 1894. From 1896 to 1911, he played for the USA against England in 13 trans-Atlantic cable matches, without a single loss. He was the only American master to play against five world champions: Johannes Zukertort, Wilhelm Steinitz, Emanuel Lasker, José Capablanca and Alexander Alekhine.

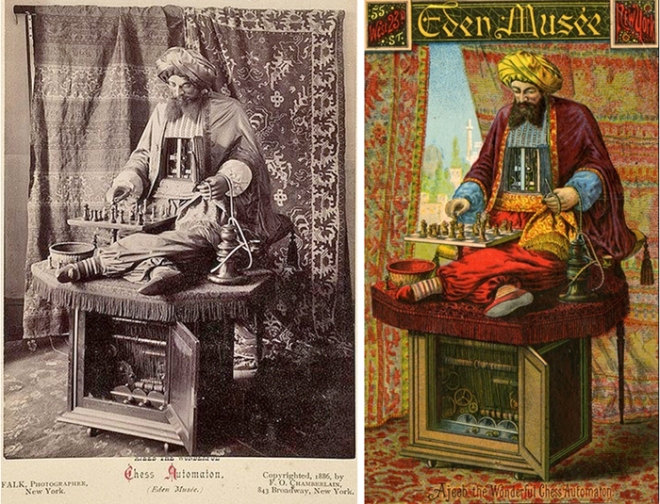

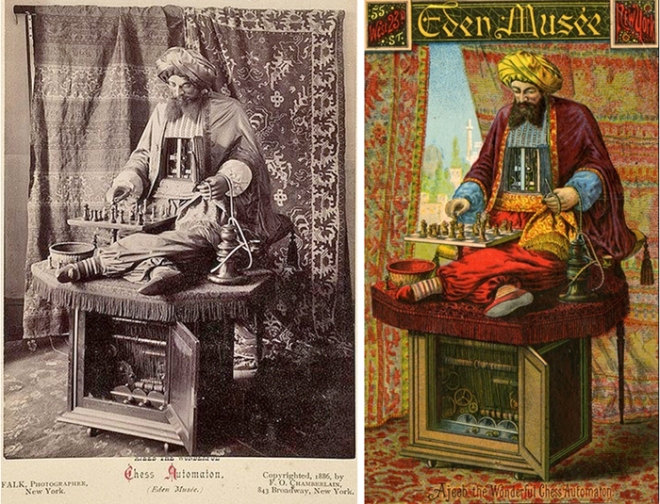

One of the most famous chess opponents of the nineteenth century, however, was not a man, but a machine. Ajeeb, a clockwork chess automaton, was a star attraction at the Eden Musée in New York City.

Ajeeb consisted of a robed figure seated atop a cabinet, addressing a chess board. Before each game, the operator opened the doors of the cabinet to show that no one was inside. Then he wound up Ajeeb, and play began.

Inside, however, having moved from one side to the other to avoid being seen during the opening of the doors, was a real chess player, a cramped but well-paid player who worked by the light of a single candle, noting the opponent’s moves and guiding Ajeeb’s hand in the appropriate response.

Hodges did not play against Ajeeb. Rather, as a young man in New York, he was one of those who played inside Ajeeb. I have to believe he was more comfortable on the porch of the Packwood, enjoying the breeze off the lake.

* * *

New York State Chess Association Mid-Summer Meetings in Skaneateles

August 27-30, 1889

July 21-25, 1891

August 1-6, 1892

July 30-August 3, 1895

Chess players gather for a photo on the porch of The Packwood House

* * *

A final note on Albert Hodges: He apparently never got show business out of his blood. In 1916, he began appearing in silent films, as a Russian official in War Brides (1916), a police inspector in The Auction Block (1917), the coroner in Empty Pockets (1918 ) and a butler in False Faces (1919).